Summers, Trichet discuss euro

The current status of the new currency is assessed, debated in talk

Now that the franc, the mark, and the lira have followed the ducat, the doubloon, and the Louis d’Or into numismatic superannuation, economists have been watching with great interest to see how well the successor to these national currencies – the euro – has been doing at replacing the monetary systems of a dozen linguistically and culturally diverse countries.

A series of public information events, collectively titled “Five Years of the Euro,” is currently under way to instruct the public about the European Union’s (EU) progress in establishing a uniform currency among its member nations.

Organized by the Center for European Studies (CES) in response to a request by the delegation of the European Commission in Washington, D.C., and co-sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the series brings together leading figures from academia, policy-making, and the financial sector in the United States and Europe to discuss the economics, politics, and governance of the EU’s Economic and Monetary Union.

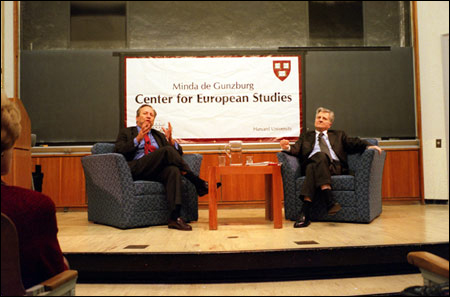

The series’ keynote event took place at Harvard on March 25 – a discussion between Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers and Jean-Claude Trichet, president of the European Central Bank (ECB). Alberto Alesina, the Nathaniel Ropes Professor of Political Economy and chair of the Economics Department, was the moderator.

Trichet, whose eight-year appointment began in November 2003, has held important economic and financial posts in the French government, formerly serving for two terms as governor of the Banque de France. He and Summers became acquainted during the latter’s appointment as treasury secretary during the Clinton administration.

Alesina’s first question brought out the complex and changing nature of the international economic situation. With 12 European countries having already adopted the euro, with more expected to come on board in the near future, and El Salvador having recently adopted the U.S. dollar, was the world moving away from the concept of “one country, one currency”?

“Yes, I think there is a trend in that direction,” said Trichet, pointing out that 64 countries are now engaged in some sort of monetary cooperation, in many cases involving the use of a shared currency. However, he added that the ECB, which has the responsibility of maintaining the euro’s stability, discourages countries from adopting the currency unilaterally. Countries must first join the EU and qualify economically before they can earn that privilege.

“There is no quick fix to adopting the euro,” Trichet said.

Both Trichet and Summers agreed that the ECB has succeeded admirably in endowing the euro with stability and credibility. What was less certain was extent to which the EU has sacrificed productivity and growth to secure these qualities, a trade-off exemplified by the gap in annual growth between the United States and Europe (3 percent versus 2 percent).

“You bought credibility, and that was a great achievement,” said Summers. “But the question is, did you overpay in terms of lost output?”

Trichet agreed that certain structural reforms in the ECB’s monetary policies will be necessary in the future in order to achieve a higher growth rate, but he argued that the bank’s efforts to ensure stability have contributed to the region’s prosperity over the last five years. Trichet was especially enthusiastic about the EU’s growth during this time.

“The European endeavor has been exciting, extraordinary! We started with six ‘founding fathers’ [Belgium, West Germany, Luxembourg, France, Italy, and the Netherlands], and now we have expanded to the level of the continent.”

In addition to the six original members, the EU now includes Austria, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

On May 1, 10 new countries – Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia – will join the 15 nations that now comprise the EU. Bulgaria and Romania are expected to follow a few years later, and Turkey is also a candidate for future membership.

With all these countries joining the EU, the question might be asked, what are the economic and political implications for the United States? As Alesina put it, “How should the U.S. view this process? Should it be happy at the unified voice of Europe?”

The kind of relationship to be avoided, Summers warned, is one in which Europe and the United States stand in opposition to one another, in which Europe strives to contain the United States, while the U.S. pursues a policy of divide and conquer.

Trichet agreed that hostility and mutual mistrust are to be avoided.

“We need a relationship of trust and partnership with the United States,” he said.