Haunting tale of ghostly revenge

13th century playwright collaborates with contemporary writer, director, composer

You won’t find brooms like these at Home Depot. Made to order in the American Repertory Theatre (A.R.T.) scene shop, they feature Plexiglas handles and fiber-optic bristles whose tips are bobbing pinpoints of white light.

At a rehearsal in late November, the cast of “Snow in June” is trying them out for the first time. Having practiced their snow-sweeping dance with plain sticks, they find the heft and balance of the brooms takes some getting used to. But the difficulty scarcely detracts from the beauty of the elaborate choreography, which seems to combine elements of baton twirling with tai chi.

The transparent, glow-in-the-dark brooms are the idea of director Chen Shi-Zheng, who wanted all the play’s props made of see-through plastic, a material he believes symbolizes the modern world. The plastic props are part of a collaborative effort to modernize this 13th century Chinese drama of innocence accused.

‘Snow in June,’ American Repertory Theatre, Loeb Drama Center, 64 Brattle St., through Dec. 28. Tickets $12 to $69. For information, call (617) 547-8300.

The original version, “The Injustice Done to Tou O” by Kuan Han-ch’ing, tells the story of the daughter of a poor scholar who is left with an elderly widow when her father goes to the capital to study. In his absence, the girl is falsely accused of murder and executed. She prophesies that if she is killed, the world will turn upside down and snow will fall in June.

In the original play, written during the repressive Yuan dynasty when China was controlled by Mongol invaders, the girl’s father returns too late to save her, but in time to punish those who brought about her death. But the creators of the A.R.T. version decided to kick it up a notch. In their play, Tou O returns as a ghost and slaughters her enemies.

“…which suggests that you can take the nicest, sweetest, most wonderful woman in the world, and turn her into a homicidal maniac if you treat her badly enough,” says writer Charles Mee, who adapted the ancient text.

Mee, Chen, and composer Paul Dresher have been working on the play since June. The three collaborators bring to the project a staggeringly eclectic array of backgrounds and perspectives.

Born in China, Chen began his career as a performer and director in traditional Chinese opera, or kunju. He came to the United States in 1987 in search of greater artistic freedom and has since directed many productions that combine elements of Chinese and Western theatrical practice. Recently, he staged Monteverdi’s “Vespers” for Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society.

Mee’s previous work includes modern adaptations of ancient Greek and Chinese plays, as well as works of history and biography dealing with figures as diverse as Erasmus, Rembrandt, and Warren G. Harding.

Dresher, the third member of the creative triumvirate, shares the adventurous and wide-ranging spirit of his collaborators. Dresher has done it all, from blues and rock to electronic music to African drumming, Javanese and Balinese gamelan, and North Indian classical music. His electro-acoustic band, the Paul Dresher Ensemble, plays its own experimental music and performs the work of other contemporary composers.

For “Snow in June,” Dresher has composed a series of songs that draw on the traditions of American roots music – Delta blues, bluegrass, Tex-Mex, gospel, and Cajun. These earthy tunes accompany scenes that dramatize the heroine’s life on earth, while the story of her ghostly revenge is characterized by more harmonically complex effects that evoke European symphonic music. All the music is played by Andromeda, a folk and world music quartet.

Dresher, who lists Bach, Chopin, Bill Evans, and Elvis Costello among his favorite composers, disavows any tendency to privilege one form of music over another.

“People should listen to music without any sense of boundaries. Too often, when people develop a deep knowledge of one musical style, they think that style is superior to all others. It’s a very blindered perspective. It shuts you off from other musical experiences.”

Significantly, the careers of all three men demonstrate a similar dislike for artistic boundaries, which is perhaps why they have gravitated toward one another and welcome the chance to collaborate.

“No one is concerned with asserting his identity in this project,” says Dresher. “We just want to make a work together.”

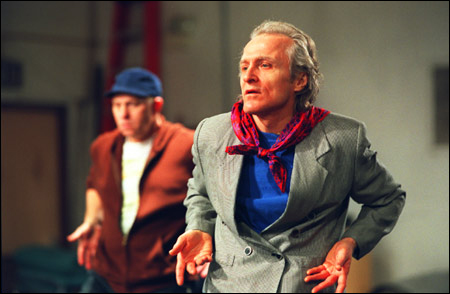

Now the cast is running through the play’s first act. The inhabitants of the town in which the heroine meets her unjust fate recite a litany of platitudes about justice, benevolence, and the inherent goodness of people, while Qian Yi, the actress who plays Tou O, now simply called “The Girl,” enters in her ghost form, gliding among them with tiny shuffling steps and lamenting her misfortune in a keening counterpoint.

A few minutes earlier, Qian Yi, dressed in black stretch pants and a sleeveless white top, was chatting and joking with other members of the cast and crew, an attractive but otherwise unremarkable member of the flesh-and-blood world. Now with her haunted, staring eyes and stylized gait, she creates an effect that is decidedly eerie.

The scene’s capacity to elicit a powerful emotional response is reassuring. “Snow in June” is composed of so many disparate elements – a 13th century Chinese story, a modern text, American roots music, and high-tech staging – that one wonders whether its parts can cohere into a theatrically effective whole.

A glance at the evolving production suggests that they can, and that the whole may even turn out to be more than the sum of its exotic and wildly heterogeneous parts.