Yenching

The singular history of a singular library

The Harvard-Yenching Library is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year – not all that old compared with its parent institution, created when John Harvard left his 300-plus book collection to the commonwealth’s fledgling college in 1638. But it is old enough to have been a constant in the lives of some of its most devoted users.

“I have used the Harvard-Yenching Library most of my adult life,” said William Kirby, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, at a reception Oct. 16 commemorating the library’s anniversary. Kirby, a historian of modern Chinese history and former director of the Asia Center, said that he has benefited from the library’s superb collections from his days as a Harvard graduate student until the present.

He also expressed confidence that the library would continue to serve succeeding generations of scholars.

“Students graduate, and faculty, in the fullness of time, retire, but libraries endure and reinvent themselves in ever more dynamic ways.”

The library’s history, and the events planned to celebrate its passing of the three-quarter-century mark demonstrate that Harvard’s repository of East Asian literature is indeed reinventing itself in ever more dynamic ways. A two-day conference on print culture in East Asia from the earliest bronze and bamboo inscriptions to today’s digital technology attracted 250 scholars Oct. 17 and 18. Meanwhile, four exhibitions, dispersed around campus, celebrate the library’s status as the largest and most comprehensive East Asian collection among all academic libraries in the West and highlight aspects of East Asian culture.

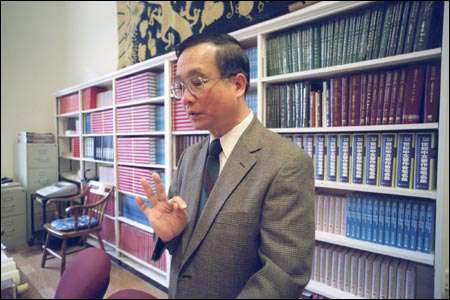

“We already have a marvelous collection, but the job is not done,” said Harvard-Yenching librarian James Cheng. “We need to update our technology, improve our services, but we also have to recognize that these are only tools, not ends. The end is always the collection. The collection is the soul of any great library.”

The library’s collection traces its origins back to 1879 when a Chinese scholar named Ko K’un-hua was invited to come to Harvard to provide instruction in the Chinese language. The small collection of books that Ko brought with him became the nucleus of the collection.

In 1927, Harvard University librarian Archibald Coolidge recruited Alfred Kaiming Chiu to organize the growing collection. Chiu had come to Harvard in 1925 as a graduate student in agricultural economics. The recipient of a traditional Confucian education, he had been selected by the Chinese government to study Western learning, first at Western-run schools in China and later at the Library School of the New York Public Library. From there he entered Harvard as a Ph.D. candidate in agricultural economics.

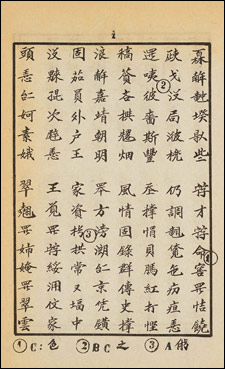

In 1931, the growing collection was transferred from Widener Library to the Harvard-Yenching Institute, founded in 1928. By the time of his retirement in 1964, Chiu had built the library into a resource of hundreds of thousands of publications and an unparalleled collection of rare books and manuscripts. He also devised the first successful system for cataloging books in Chinese and Japanese. Known as the “Harvard-Yenching Classification System,” it was adopted worldwide and remained in use for the next 40 years.

Eugene Wu took over the librarianship in 1965. Under his leadership, the library’s holdings more than doubled, going from 407,424 volumes to nearly 900,000 at the time of his retirement in 1997. During his tenure, the collection evolved from one that was predominantly humanistic to one that encompasses East Asian materials in a broad range of academic disciplines.

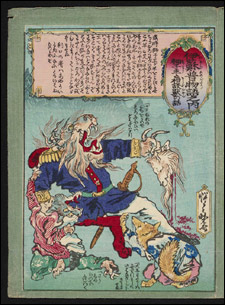

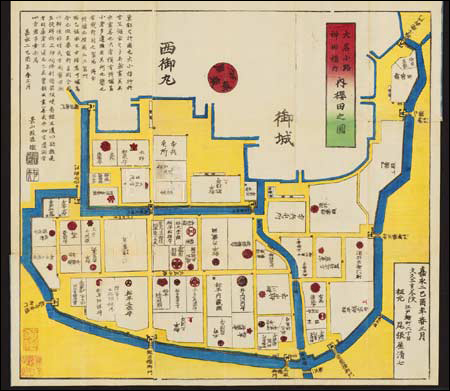

An exhibition at Houghton Library brings together rare and unusual items from the Harvard-Yenching Library’s special collections. Included are materials from China, Japan, and Korea, some dating to the Song Dynasty (960-1279). There are ancient manuscripts, examples of early Chinese printing (the Chinese invented moveable type about 400 years before Gutenberg), Buddhist and Shinto scrolls, books of history and travel, illustrated works of literature, military treatises, and much more. The exhibition provides a rare opportunity to see some of the library’s most treasured holdings.

At the Peabody Museum, viewers can see a selection of old photographs of China drawn from archives at the Peabody and the Harvard-Yenching. Pusey Library has an exhibition of ephemeral materials from East Asia – posters, handbills, advertisements, letters, etc. And at the Law School Library in Langdell Hall, one can view rare Chinese and Japanese legal documents and manuscripts. All the exhibitions are open to the public and will be on display until the end of the year.

“In celebrating the library’s anniversary, we are celebrating the achievements of my predecessors,” said Cheng, who was appointed librarian in 1998. “The more I learn about the collection, the more I appreciate what has been accomplished.”

Born in Hong Kong, Cheng studied modern Chinese intellectual history and library studies as a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Before coming to Harvard, he was head of the Richard C. Rudolph East Asian Library at the University of California, Los Angeles.

During his stewardship of the library, Cheng has set himself three main goals: to maintain and further develop the collection, to improve public services to help scholars gain easier access to the library’s holdings, and to introduce new and better technology. He is already well on his way to achieving the last goal. Completing a task started under his predecessor, he has completed the digitization of the library’s entire catalog, with Chinese, Japanese, and Korean characters now displayed along with romanized entries on the HOLLIS system.

Other ongoing projects include the digitization of several collections of old photographs and a collection of Chinese women’s writings from the Ming and Qing periods.

“We are now in a position to generate digital and electronic resources and to make them available to scholars worldwide,” said Cheng.

Another of Cheng’s goals is staff development. “In any organization, the biggest asset is people. Management has a professional and moral obligation to give promising younger colleagues the opportunity to learn and grow so that the organization can continue to flourish,” he said.