Making Harvard modern

As designer and Design School dean, Sert pushed the envelope

This fall two exhibitions and a symposium commemorate the 50th anniversary of the appointment of Josep Lluis Sert as dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD).

The lobby of Gund Hall, evoking Sert’s native Catalonia with its newly painted red and yellow walls, features plans, sketches, photos, and models of Sert’s projects from his never-realized renovations of Bogotá and Havana to the signature buildings he created for Harvard, Boston University, and New York City’s Roosevelt Island. The exhibition, titled “Josep Lluis Sert: The Architect of Urban Design,” runs from Oct. 6 to Nov. 19.

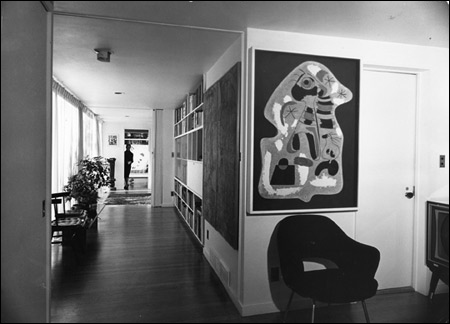

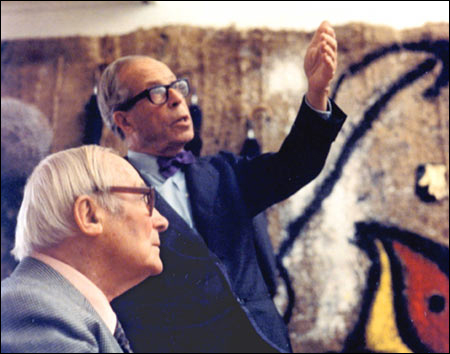

Meanwhile, in the gallery named for him in the Carpenter Center (a building designed by Sert’s mentor and colleague Le Corbusier), another exhibition celebrates Sert’s involvement with the arts. Sert came to prominence in 1937 as the designer of the Spanish pavilion at the International Exposition in Paris, a project undertaken in the midst of the Spanish Civil War. Picasso’s “Guernica,” a graphic scream of protest against the bombing of a Spanish town by Franco’s Nationalist forces, made its debut there, accompanied by works by Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, and other 20th century artists.

Sert was a friend of these and other important artists throughout his life, and the house he designed for himself at 64 Francis Ave., Cambridge, served as a gallery for his impressive collection of modern art.

“Josep Lluis Sert: Architect to the Arts II” will be on view at the Carpenter Center through Dec. 14. Both exhibitions were organized by special collections librarian Mary Daniels and project archivist Inés Zalduendo. A symposium, bringing together major scholars studying Sert’s work, will take place at the GSD on Oct. 24 and 25.

Sert has had a major impact on Harvard’s built environment, with three major buildings designed by his Cambridge-based firm, Sert, Jackson and Associates – the Holyoke Center (1958-65), Peabody Terrace (1962-64), and the Science Center (1968-73).

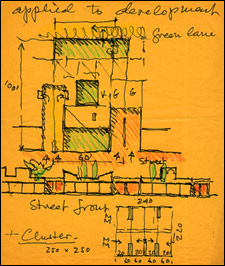

While to the casual eye, these cast-concrete structures towering above the older red-brick and wood fabric of the surrounding environment may seem defiant singularities, they were in fact, as the GSD exhibition makes clear, designed to integrate themselves with their surroundings. It was Sert who in 1959 established the degree program in urban design at the GSD, and in his own architectural work he never lost sight of the contextual role of the buildings he created.

The Holyoke Center’s arcade, for example, was meant to function as a covered walkway linking Mt. Auburn Street with Harvard Yard. The Science Center is built around two intersecting corridors that meet at a central crossroads, creating, in Sert’s vision, an academic village that would reinvigorate the relationship between students and faculty.

And Peabody Terrace, the housing complex for married graduate students that owes its existence to the advocacy of President Pusey’s wife Anne, was designed to create a sense of community for its residents while inviting its neighbors to enjoy its public plazas and walkways.

“These projects were very much about pedestrian linking,” said Daniels. “Sert was very sensitive to existing patterns of land use and designs that could be incorporated into new plans. He was very sincere in his belief in the good effects that architecture could have on people’s lives.”

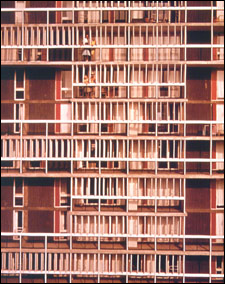

But despite Sert’s good intentions, his projects have reaped their share of negative reactions. The magazine Architecture Boston has focused attention on the controversial aspects of Sert’s work by devoting its July/August 2003 issue to an examination of Peabody Terrace, expressing the essential disagreement about the work in the form of a stark conundrum: “Architects love Peabody Terrace. The public hates it.”

In fact, the public’s hostility to the structures may be in proportion to its degree of proximity, with the most intense feelings confined to those households on the front lines of the town/gown divide. Nevertheless, a perceptual disparity does exist.

Representing the architects’ point of view, Leland Cott, an adjunct professor of urban design at the GSD, calls Peabody Terrace “a model of design efficiency, economy, and attention to scale.” He comments on the way Sert set the three 22-story towers well back from the street, grouping three-, five-, and seven-story structures around them to create a gradual transition with the surrounding neighborhood.

Otile McManus, in a companion essay, discusses the reactions of many Cambridge residents, who have described the complex as “monstrous,” “cold,” “uninviting,” “overwhelming,” and “hostile,” and have compared it to Soviet housing.

The three towers with their visually lively facades have been the objects of particularly intense ire by community members. And yet Sert, with a very different eye, saw them as the modern equivalent of the cathedral towers and campaniles that rose above the rooflines of medieval towns.

There are pragmatic issues as well. As Daniels points out, “On a very constrained site that demanded a high density of use, the only way to build was up or down.”

In a sense, the controversy over Sert’s designs is a controversy over modernism itself, a philosophy of art and design which has never truly won universal acclaim despite the passage of nearly a century since its first practitioners challenged prevailing 19th century styles. In architecture, Sert represented the second generation of modernist designers, whose ideas gained institutional acceptance without ever really winning over the hearts and minds of the public at large.

There may be those who will never quite warm up to Sert’s minimalist concrete slabs and colored aluminum panels the way they do to the textured brick and neoclassic details of Harvard’s older buildings. But these exhibitions can help even the most militant anti-modernists to educate themselves about the designer’s intentions and the ideals that inspired his long and influential career.

“He was very much a spirited citizen, not a closeted academic,” Daniels said. “He took his responsibilities as a citizen very seriously.”