‘Creativity is for everyone’

Choreographer Twyla Tharp makes claims for universality of talent

Be habitual. Get organized. Make decisions.

Such advice would sound more natural coming from a business guru than from an icon of contemporary dance hailed for her wildly inventive choreography.

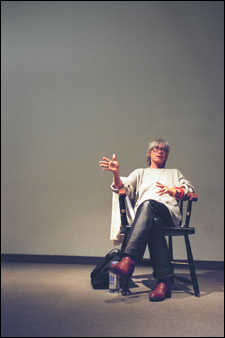

Which is precisely the point, choreographer Twyla Tharp told an audience at the Sackler Museum Wednesday (Oct. 15). In an event co-sponsored by the Harvard University Art Museums’ author series and the Harvard Book Store, Tharp described how the creative impulses that have driven her 35-year career are accessible to anyone – artists, businesspeople, and at this lecture, a librarian – who wants to imbue their lives or work with creativity.

“Art is sometimes approached and encouraged by those who practice it as an elite form. I don’t buy that,” said Tharp in the interview-style lecture with local dance critic Debra Cash. “I think that everyone is gifted, everyone is talented, and it is just a question as to how does one want to pursue this and how committed is one willing to be.”

In pursuit and commitment, she said, lies “creative habit,” an oxymoron she used for the title of her new book, “The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life.”

“It’s a practice and it’s a daily practice, and it’s a commitment,” she added. “But it is available to everyone.” She likened what she calls a “white room” – the empty space of creative possibility – to the painter’s blank canvas or the business leader’s yet-unmade decision.

“Preparation, hard work, and good habit … these things are absolutely necessary to anyone wanting to accomplish something, whether the creation of a dance or the proposal of a new product,” she said.

Getting unstuck

Such a workaday ethic has served Tharp well. Hers is one of the most distinctive creative sensibilities in modern dance in the past several decades; she has created more than 125 dances for her own company as well as many others and has choreographed for television, film, and Broadway. Most recently, she conceived, directed, and choreographed the Broadway musical “Movin’ Out,” set to the music of Billy Joel, for which she won a Tony Award.

One habit Tharp advocates is that of physical motion. Hardly surprising for a dancer, but how would it work for, say, a librarian? To illustrate its effectiveness, Tharp enlisted two volunteers to enact a verb in front of the audience. Local librarian Naomi Allen ran – back and forth in a small space on the stage – until Tharp and audience feedback observed she was “stuck.”

“Unstick,” commanded the choreographer, and her newest recruit gamely fell to her hands and knees to “run” on all fours. “The point of the exercise is don’t go on automatic,” said Tharp.

Afterward, Allen reported that her impromptu dance left her feeling energized. The second volunteer, dancer Kristen Engebretsen, told Tharp she was “invigorated and engaged,” responses which obviously pleased Tharp.

“I didn’t pay them anything,” she insisted. “This will work for anybody, I guarantee you.”

The business of creativity

Tharp comes by the business end of her new book honestly: She is one of the more financially successful artists among modern dancers, typically the hungriest of the proverbial starving artists. Simultaneously prickly and charming, she opened her discussion with a blunt response to Cash’s first question.

“Why write a book? Shall I be crass?” she asked, more as a warning than a request for permission. “You don’t get paid in advance for doing a Broadway show.” Her advance fee for “The Creative Habit,” pitched as much toward business and self-help readers s dance aficionados, was generous, she said.

She was similarly unapologetic when detailing the salary negotiations for the dancers in “Movin’ Out.” When she brought dancers from her own company, Twyla Tharp Dance, into the handsomely funded Broadway production, she secured some of the highest salaries in the business of dance.

“I feel that dancers are certainly the equivalent of athletes,” she said, and their performances are akin to those of movie stars. “I want our culture to acknowledge them.”

For more author events at the Harvard University Art Museums, visit http://www.artmuseums.harvard.edu/events/authorevents.html.

Yet for all but young artists launching their careers, Tharp spoke out against subsidies and charity. “I feel that art has a responsibility in this culture to pull its own weight,” she said. She credited her friendship with photographer Richard Avedon for helping her learn skills of self-subsidy. Just as Avedon shot fashion to support his “art” photography, so Tharp choreographed for film (“Hair,” “Amadeus,” “White Nights”) to pay for her son’s schooling while she created dances for her own company.

“Why shouldn’t I be paid if a plumber be paid?” she asserted. “And why shouldn’t we be acknowledged for what we do, what we bring, and the value we have in a culture. We’re not children.”

Older and wiser, but no less inspired

Tharp fielded questions from an informed and adoring audience about knowing when a work is finally done, about failure (“I’m a great believer – though not a great lover – of failure”), and about the challenge of documenting dance. Although videotape and several different methods of written notation attempt to record dance, they are not wholly successful at preserving its essence. “Dance is the only art form without an artifact, which is why it is way at the bottom of the heap,” she said.

One audience member asked her to compare her current work and philosophy with that of the 25-year-old Tharp who burst on the scene in the 1960s. Her younger self “didn’t know what a dance was or what she wanted it to be when she stepped into a studio. She wanted it to reveal itself to her, she wanted it to come to her,” she said, returning to the thesis of “The Creative Habit.” Now, the practicality of renting studios and paying dancers demands more forethought; awaiting a visit from the muse gets downright expensive. “But that is not to say that I consider myself less creative or less inspired,” she said.