Affirming affirmative action

Faculty explore subtleties of issue at GSE forum

A boldly worded title – “Do the Right Thing: Why Harvard Supports Affirmative Action and Why Every College Should” – left little room for doubt about the positions of the panelists at the Graduate School of Education’s (GSE) Askwith Forum Tuesday (April 8). Indeed, it was by explicit design that the panel, co-sponsored by the GSE’s office of student affairs, assembled some of the University’s loudest cheerleaders for affirmative action but none of its critics.

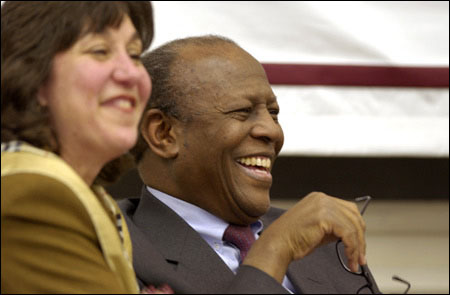

Rather than fostering a point-counterpoint debate that reduces each side to simplified sound bites, the event organizers hoped to probe the subtleties and nuances of affirmative action in higher education. They hit their mark: The panelists – former Harvard President Derek Bok, Law School Professor Lani Guinier, Gary Orfield and Angelo Ancheto of the Civil Rights Project, and sociologist Charles Willie – offered a diversity of viewpoints that made for a full exploration of the issue as well as, at times, lively debate.

With the constitutionality of affirmative action in higher education under scrutiny by the U.S. Supreme Court, the panelists shared their own awakenings to the importance of affirmative action. Judith McLaughlin, lecturer on education and director of the higher education program at the GSE, moderated.

To Willie, professor of education emeritus, and Civil Rights Project Director of Legal and Policy Advocacy Programs Angelo Ancheto, support for affirmative action is rooted in their personal experiences as an African American and Asian American, respectively. Yet both stressed the impact the policy has on all segments of American society, not just racial minorities.

“All knowledge is partial,” said Willie. “The knowledge of all of the people who are present ought to be used to help solve the problems this nation, this city, this university faces.”

Bok, who is University Professor at Harvard, co-authored, with William Bowen, one of the landmark books on affirmative action in higher education, “The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions.” Arriving at Massachusetts Hall as Harvard president in 1971, “I came to understand how important diversity, in all of its aspects, is to the process of education as we conceive it in Harvard College,” he said. Many of Harvard’s institutions, from admissions policies to the house system, are built on the premise that students of diverse talents, backgrounds, races, and religions enrich each other’s educational experiences, he noted.

Is affirmative action enough?

Guinier, Bennett Boskey Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, challenged the panel to think about ways in which affirmative action does not go far enough. “I think you need to consider both race and class. In many ways, affirmative action is too weak to truly diversify Harvard or any other institution that has such an imbedded preference for wealth in its admissions practices,” she said.

She cited a recently released study that found that 74 percent of students at the nation’s 146 most selective colleges came from families in the top 25 percent income bracket, while only 3 percent of students at those schools came from the bottom quartile.

“We have a preference for affluence and the problem is we call that merit,” she said.

Countering Bok’s strong disagreement to her statement, Guinier clarified that hers was not a charge of conspiracy. “My real point is that our overreliance on the SAT and the LSAT is, in itself, a preference for affluence, because those tests … don’t correlate with performance in school.” They do, however, correlate quite neatly with students’ wealth, she said.

Orfield, professor of education and social policy and co-founding director of the Harvard Civil Rights Project, cautioned against framing the discussion of race or income preferences in college admissions as an either-or. Many civil rights issues, he said, “are posed as if you have to choose one or the other … by people who don’t want to do either.”

Exploring the alternatives

Anticipating that the Supreme Court will rule this summer on the constitutionality of the University of Michigan’s use of affirmative action in admissions to its law school and undergraduate college, the panelists offered theories on what might happen if the nation’s highest court declares affirmative action in university admissions unconstitutional.

“I think we can predict very well what would happen if all the colleges and professional schools in the United States simply adopted race-blind admissions, and that would be a drastic drop in underrepresented minorities,” said Bok.

Yet that’s unlikely, said Bok, pointing to states where the use of preferential admissions has been outlawed already and other systems have been implemented to attempt to diversify higher education. However, such alternatives are less effective than affirmative action, he said.

Orfield, who has studied these alternatives, agreed. “To make alternatives work, you have to invest a lot of money in recruitment, outreach, targeting segregated high schools,” he said, and still alternatives have not met with success. “They’ve only worked during a period of economic boom, and right now all of our state education systems are experiencing large cutbacks,” he added.

Audience questions further poked at some oft-ignored issues of affirmative action, such as the dangers of tokenism and the feeling of stigma some minority students have.

“Stereotypes need to be broken down,” said Ancheto. “It’s through affirmative action admissions programs that people understand that you’re not just a black student sitting in a classroom, that you are an individual who among other things is black.”