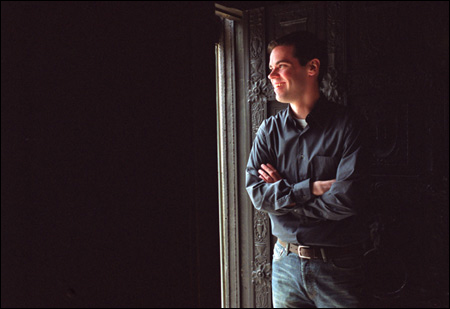

Graduate student Scott Sowerby finds surprising side to King James II:

English ruler, known to history as an autocrat, was ahead of his time on matters of religious tolerance

If there is one thing people are likely to know about King James II of England, it is the year his reign ended – 1688.

This was the “Bloodless” or “Glorious Revolution,” when James, abandoned by many of his supporters and facing an invading army from the Netherlands led by his son-in-law William of Orange, fled to France and exile. The king’s defeat removed the threat that the Catholic James would somehow drag England back into the arms of the Church of Rome. With William and Mary as heads of state, the country was once more safely Protestant. To this day, membership in the Church of England is a prerequisite for accession to the British throne.

Surely, James must have been a dismal failure as a king to have inspired his erstwhile subjects to call his expulsion “glorious,” and for many years, historians assumed this to have been the case.

But what if James fell, not because he was arrogant and obtuse, but because he held ideas and convictions that were centuries ahead of their time? What if James II were a religious pluralist, an advocate of tolerance and the primacy of the individual conscience, well before such a perspective became a popular, if not obligatory, doctrine for modern democracies?

History graduate student Scott Sowerby has combed through archives throughout England and found evidence that he believes will change the way historians view James II.

“It’s clear that James was supporting religious toleration,” said Sowerby. “But most historians have seen that as a mask he would have dropped once he achieved his ends. I’ve found more evidence than anyone else that his religious tolerance was real.”

Sowerby’s most striking piece of evidence is a diary he found in a small, obscure record office in northern England in which the diarist recorded a speech made by James. In the speech, the king makes a striking comparison between racial and religious toleration.

“Suppose there should be a law made that all black men should be imprisoned, it would be unreasonable. We have as little reason to quarrel with other men for being of different opinions than as for being of different complexions.”

As far as he knows, Sowerby is the first scholar to read this diary. Discovering the transcription of the king’s speech was an electrifying experience.

“I got chills down my spine. I had to stop working for about a half-hour. It’s important because he’s made a mental leap that few others had made at the time.”

One of those who had made a similar leap was James’ contemporary John Locke in “A Letter Concerning Toleration” (1689). Locke says it is just as unfair to persecute people for their religion as it is to persecute them because of the color of their hair or eyes.

Ironically, Locke was a member of the party that sought to depose James. Is it possible that the philosopher and the king might have held similar views?

“I’m positioning James as being more liberal than John Locke. That’s certainly different from the way he’s been seen in the past,” Sowerby said.

Historians have long known that James advocated toleration for Quakers, who were being persecuted at the time. In fact, James was a friend of William Penn, the aristocratic convert to Quakerism and founder of Pennsylvania.

In 1687, the two men traveled around England together speaking on behalf of religious toleration. Most historians have assumed that James’ concern for the Quakers was feigned and that he was using Penn to help him secure acceptance for Catholics. But Sowerby believes that James was making a genuine attempt to reach out to Quakers.

For James, the final crisis began when his second wife became pregnant and gave birth to a male heir. The child automatically became first in line for the throne, ahead of James’ grown daughters, Mary and Anne. For supporters of the Church of England, James’ happy event raised the spectre of a Catholic dynasty.

Then in 1688, James issued the Declaration of Indulgence and required that it be read in all churches. The Declaration, which James called his “new Magna Carta,” removed legal restrictions affecting Catholics and dissenting Protestants. Seven bishops refused to comply with James’ order, and he had them imprisoned in the Tower of London. It was soon after this that James’ enemies in Parliament invited William of Orange to invade England.

Historians have interpreted these events to show that James’ zealous support for Catholicism alienated an increasingly large portion of Parliament until finally the king stood alone, a victim of his own stubbornness and bad judgment. But Sowerby sees James’ struggle with Parliament differently.

One of the documents he has discovered in his three-and-a-half-year excavation of 17th century English archives is a diary kept by a member of the House of Commons during these years of conflict.

“Historians have believed that most members of Parliament opposed James’ policies, but this diary shows that in fact Parliament was very sharply divided.”

Sowerby believes that James, rather than being an autocrat who tried to force an unwelcome religion on his subjects, was in fact an advocate of religious toleration whose vision of a nation in which each person was free to worship as he or she saw fit was too threatening to the Protestant establishment.

“You could say he went too far too fast.”

Sowerby, a Canadian Baptist who has always been fascinated by the religious passions that gripped England and other European countries in the 17th century, said that his work does not come out of “pro-monarchy sentiment.”

Nor does he identify with the Jacobites, those supporters of James II who continued to champion his cause and that of his heirs. Jacobitism still exists in England in the form of drinking societies, and Sowerby wonders whether he will receive speaking invitations from these groups when his work is published.

But he does believe that James has been given a raw deal and feels an ardent desire to change the way he is viewed.

“I think he’s been unfairly slandered for a long time. He deserves to have someone argue his side. I’d like to be his public defender.”