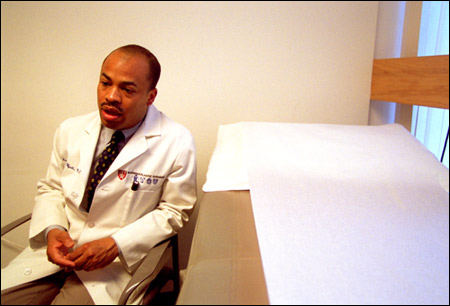

Dr. Wyatt Goes to Washington:

HMS resident mixes politics, plastic surgery

When Lance Wyatt strayed from his career path as a surgeon to spend a year in the White House, many of his colleagues and mentors in the medical field looked at him with curiosity and skepticism.

Yet for Wyatt, currently chief resident in plastic surgery in the Harvard Combined Plastic Surgery Residency Training Program, medicine and public policy have never been an either-or proposition.

“I view myself as a citizen who happens to practice medicine, who happens to have chosen plastic surgery,” says Wyatt, who is also a clinical fellow in surgery at Harvard Medical School. “As a citizen, I believe that it’s important for you to take part in the issues of the day.”

For physicians like Wyatt, those issues today are as likely to be influenced by lawmakers as they are by those directly involved with health care delivery. That’s why Wyatt, who spent four years in medical school and seven years as a general surgery resident at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), stepped off the top rung of the training ladder in 1999. Instead of becoming a chief resident in general surgery at UCLA, he traded his white coat for a suit coat to become one of 16 White House Fellows in 2000.

It wasn’t an easy decision, he recalls, and he was discouraged by colleagues and mentors who had invested in his medical training and considered a year of policy-making a distraction.

“But there was also a group within that department that said, ‘Hey, one day, with him having these experiences, we might be better off, medicine might be better off,’” he says. For Wyatt, who did in fact return to medicine and is finishing his training in June, the year in Washington was a powerful experience that helped him chart a new career direction.

A proactive participant in the future of medicine

Wyatt’s political awakening came in the 1990s, when his residency coincided with sea changes in the field of health care. During that time, managed care grew to dominate, an increasing number of Americans were uninsured or underinsured, physician autonomy was being encroached upon, and several federal policies – notably President Clinton’s failed health-care policy and the 1997 balanced budget act – had major implications for those keeping America healthy.

“There were tremendous federal forces that were holding sway over the practice of health care and were shaping and molding our health care delivery system,” Wyatt says.

In 1998, Wyatt and a medical school colleague founded Health Relief International, a nonprofit organization that provides health services and supplies to indigent adults and children worldwide; a connection to a government official in Ecuador took them to that country’s poor coastal region.

His philanthropic work abroad meshed with his growing interest in health-care policy and signaled a career change, albeit temporary.

“Because I wanted to be a part of where medicine was going and be a proactive participant, I began to look into ways in which I might better be an agent of change and also better understand the forces that were influencing the practice of medicine,” says Wyatt. “The best place to cultivate those interests was Washington.”

White House Fellows, selected from as many as 1,000 applicants, serve as special assistants in the upper echelons of the White House.

“You’re basically working hand-in-hand with the senior staff and the Cabinet members,” says Wyatt, still in awe at the regular access he had to off-the-record meetings with political and lay leaders.

Working at the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Research and Development Office, Wyatt helped draft policy, field congressional inquiries, deal with media, and chair meetings. He also traveled, chairing the 2000 White House Fellows trip to sub-Saharan Africa, where he tackled issues like debt relief, HIV infection, democracy development, and poverty reduction. The experience changed him forever.

“As a result of that year I had a career shift,” he says. He now foresees a medical career that lasts about two decades before merging with diplomacy. Long-term goals include starting a program with Africa that harnesses human resources from the world’s wealthiest nations to address problems on the world’s poorest continent.

In the meantime, Wyatt has already put a policy slant on his medical studies. In addition to his work with Health Relief International, he is a Remarque Forum Fellow and a delegate to the U.S.-Japan Foundation, exploring North Atlantic relations with Europe and trans-Pacific relations with Japan, respectively. He is the American Society of Plastic Surgeons delegate to the resident and fellows section of the American Medical Institute, where he remains involved in health policy and public advocacy.

Lobbying for his patients

As issues like uninsured patients, Medicare reform, and patients’ rights continue to grab the attention of the public and of policy-makers, Wyatt is an outspoken advocate for physician involvement in the democratic process.

“Being proactive and having a seat at the debate of public policy on behalf of your patients is not a luxury. It’s a necessity,” he says. “If more physicians participated we’d perhaps have more creative solutions to the problems that plague us and our health care system.”

Even as he logs the 80-hour workweeks of a resident, Wyatt keeps a hand in the public sector; he returned to Washington several weeks ago to lobby on behalf of medical liability reform. To him, it’s all part of the same health-care package.

“If you look at caring for your patient in a broader way, of course being a participant in policy is a part of it,” he says.

Looking back on his White House year, Wyatt cites a benefit that might surprise those who believe that the creation of law, like sausages, is distasteful to watch.

“I certainly became more wise and more knowledgeable, but also I became more idealistic about our nation and its promises,” he says. “You realize that government is you. It’s not this foreign entity. If you want to be involved, be involved.”