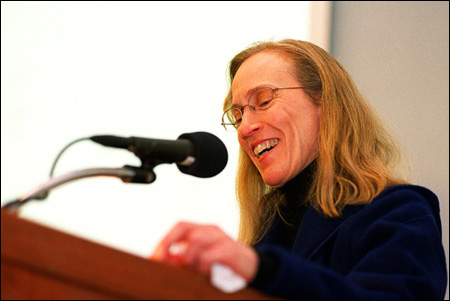

Goldin discusses impact of oral contraceptives on gender equality in the workplace

The paycheck and the pill

What is the hidden factor behind the gains women have made in the labor market since the 1970s? Claudia Goldin believes it’s the birth control pill.

Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics, discussed her research findings in a lecture Tuesday (Dec. 3) titled “An Evolving Force: The Rising and Then Declining Significance of Gender Across the 20th Century.” The lecture was sponsored by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

“Without the pill, pregnancy could derail careers,” Goldin said. “The pill reduced the risk of sex. Its indirect effect was that it led to an increase in the age of first marriages. It also eliminated one of the main reasons for marriage.”

Goldin, an economic historian who has applied her interdisciplinary perspective to a great variety of issues including slavery, the family, and the history of education, outlined the complicated story of women’s participation in the labor market in a lecture abundantly illustrated with charts, graphs, and New Yorker cartoons. The story began with the last few decades, then flashed back to the beginning of the century, finally ending with a provocative denouement.

She began with the assertion that since the early 1970s, women’s participation in the labor force has been on the upswing, now reaching almost 50 percent. Moreover, women are entering professions previously closed to them and receiving compensation that is increasingly on a par with that of their male counterparts.

Welcome though this change may be, it still raises an important question. Why is it that “real and meaningful change was thwarted through much of the century?” What happened in the late 1960s and early ’70s to change things?

In order to answer this question, Goldin went back to the beginning decades of the century, a time in which the entrance of women into the labor market actually exceeded that of more recent times. This was a time of dramatic increases in the number of women receiving high school diplomas and in the number of available white-collar jobs. The result was a huge influx of women into positions as typists, secretaries, bank clerks, bookkeepers, and sales personnel.

“With a high school degree, a woman could be free. She could be a white-collar worker in a nice office. Young women flocked to these jobs. By 1930, 44 percent of women in the workforce were white-collar workers.”

But since these were jobs requiring brains, not brawn, how was it that women did not advance as quickly as men did? In fact, the statistics show that in the first part of the century, the longer a woman remained in the workforce, the lower her wages were relative to those of a man.

Clearly, women were being discriminated against, but in a particular way that Goldin described as “the pollution model of discrimination.” Unlike racial or religious discrimination, in which one group objects to the presence of the other, men generally do not find the presence of women unpleasant. But men did feel that the hiring of women reduced the prestige of the occupation in which they were engaged, and this objection served to bar women’s entrance into these jobs.

What happened to break the logjam that maintained the unequal status of women in the workforce? Goldin rejects the “continuous change” theory in which unequal wages are explained by the fact that the entrance of unskilled women into the labor force diluted the qualifications of women in general. After women had gained more experience and skills, according to this view, their compensation began to rise.

“In actuality, the continuous change explanation doesn’t explain the changes of the 1960s and ’70s. Something big is missing, something that shocked the system.”

While several factors have been proposed, including the rise of feminism, anti-discrimination laws, and changing norms in the labor market, the effect of these changes are difficult to analyze. Only the advent of oral contraceptives – the pill – stands out as a likely, and measurable, explanation.

“The pill lowered the cost to unmarried women of pursuing careers,” Goldin said. “Before the pill, young women in college had to factor in the cost to their social life and their prospects for marriage.”

The pill was approved in the 1960s, but its effect was not fully realized until the early 1970s, ironically, as a result of the Vietnam War.

“The age-of-majority laws changed in the late ’60s and early ’70s, driven by the agitation for reduction of the voting age, under the slogan, ‘If they’re old enough to fight, they’re old enough to vote.’ The change of these laws enabled unmarried women to gain access to the pill.”

By taking control of their own reproductive choices, women were able to stay in school, train for professions, and gain credentials which allowed them to break into professions previously closed to them as a result of the pollution effect. This change has contributed to the declining significance of gender in the labor market.