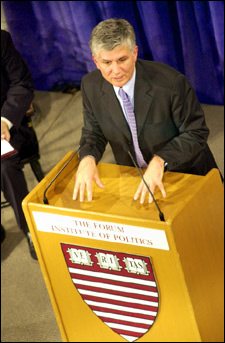

Serbian prime minister speaks:

Djindjic’s agenda: Stable political, legal institutions

Writers as far back as Sophocles have referred to the nation as a ship of state. In his talk at the Kennedy School’s ARCO Forum Friday (Sept. 20), Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic gave that metaphor a new twist. He compared his country to a bicycle.

Writers as far back as Sophocles have referred to the nation as a ship of state. In his talk at the Kennedy School’s ARCO Forum Friday (Sept. 20), Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic gave that metaphor a new twist. He compared his country to a bicycle.

“A bicycle can be stable only by moving. If you stop or look down at your legs, you will fall down. The only way to stay on track and not fall down is to keep moving.”

Djindjic became prime minister of Serbia in 2001. Serbia and the much smaller state of Montenegro now constitute the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia’s former component states – Slovenia, Bosnia-Hercegovina, and Macedonia – have since declared their independence.

Djindjic, who has been involved in pro-democracy movements since his student days in Belgrade, cooperated with democratically elected Yugoslav President Vojislav Kostunica earlier this year to send former Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic to The Hague to stand trial for war crimes.

Known as a pragmatist whose unrelenting efforts to modernize his country economically and politically often put him at odds with more moderate colleagues, Djindjic came to Harvard after a busy week of meeting with international investors in New York.

Speaking in English, the 50-year-old Djindjic seemed more like the charismatic philosophy professor he used to be than the politician he is today. In his talk, he touched on Balkan history in an effort to explain the region’s strange and precarious political situation.

“We didn’t have real opportunities to develop in a normal way,” he said. “We always had the Austro-Hungarian Empire on one side and the Ottoman Empire on the other.”

Because these larger entities frustrated the region’s nationalist aspirations, they found expression in the only way they could – through religion, myth, and poetry, Djindjic said.

“The region functions according to certain rules. Don’t say that they [the Serbian people] are outside of civilization. Don’t blame them, help them.”

Although he did not specifically mention Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing campaign and the horrors it brought about, there was no mistaking the fact that it was to this recent traumatic event that his plea referred.

Djindjic’s political agenda is to assist his country in building stable political, legal, and economic institutions and to turn away from destructive forms of nationalism rooted in religion and mythology.

“We know from experience that market economies and democracy can bring even very complicated societies to peace,” he said.

Djindjic disagrees with some of his colleagues about how these changes are to be brought about, however. While some leaders prefer to work within the confines of the existing legal system, Djindjic insists that such an approach is doomed to failure.

“Some people say they want to abide by existing laws. But the system doesn’t work. If you wait for it to work, you will wait a long time. You have to do something on your own.”

Djindjic is aware of the dangers inherent in such an approach.

“If you do things legally, there is no progress. If you take the initiative and go outside the system, how do you know you will not abuse your power, that you will not become a dictator yourself? My way out is to follow standards from outside, the standards of the European Union.”

But for a country like Serbia, which faces dismal economic conditions and a massive refugee problem, even applying European standards is no guarantee that the population will be protected from suffering.

“It is like surgery. You cannot conduct surgery without causing pain.”

Djindjic invited his detractors to use the political process to oppose him if they disagreed with his policies.

“If you have evidence that some people are profiting from the reforms, tell us, organize against us. But if you don’t want pain with the reforms, that is not possible.”

Under normal conditions, politicians in a democracy find out what people want and then give it to them, but this procedure does not work in a period of transition such as the one Serbia is now experiencing, Djindjic said.

“Most politicians want to be loved, but if you want to be loved in a difficult situation, you will miss the opportunity to do what needs to be done. We have a unique opportunity to bring these countries to peace and stability. For the first time in history, we have democratically elected governments. I hope we will use that opportunity. If not, there is also the possibility for destruction.”