What are you laughing at?

Well, Richard Pryor, Woody Allen, Peter Sellers. What about S.J.Perelman?

“Dying is easy, comedy is hard.” Reportedly, these were the last words of Sir Donald Wolfit, British actor and director. Wolfit’s deathbed quip has been quoted often, perhaps because it captures so well comedy’s essential paradox.

How is it that laughter, a behavior so basic and essential to human life that babies laugh long before they learn to walk, should be so devilishly hard to evoke – so much so that even the best efforts of professional comedians and comedy writers often fall flat?

Most of us love to laugh, and the therapeutic effects of laughter have been extolled for centuries, but who can explain what laughter is, why we do it, or what makes something funny? Few thinkers have tackled the problem, and the handful of theories that exist hardly seem to fit the elusive and protean nature of their subject.

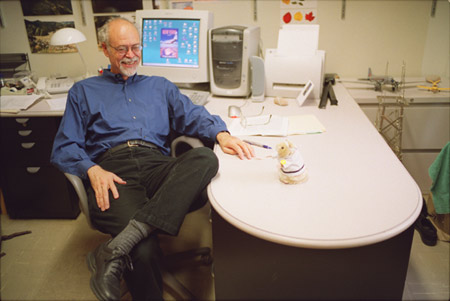

“Literary criticism has always been more comfortable with high-minded theories of tragedy than with trying to explain comedy. It’s tragedy whose existence is easy to explain and laughter that seems mysterious,” said Leo Damrosch, the Ernest Bernbaum Professor of Literature.

Not that college catalogs aren’t full of courses about subjects like “Attic Comedy,” “Early Roman Comedy,” and “The Comedies of Molière.” But as Damrosch is the first to admit, even the best schtick by Aristophanes or Plautus rarely gets even a forced chuckle from today’s readers.

“Humor gets dated fast,” he said. “It has a brief shelf life.” It is for this reason that Damrosch has limited his summer course, “Wit and Humor” to material that is actually still funny.

Instead of puzzling over obscure puns and footnoted references in the comedies of yore, students in Damrosch’s class are getting their yucks hot off the presses and movie screens. The earliest items on the reading list are by Mark Twain and Oscar Wilde, two 19th century authors whose humor, in Damrosch’s opinion, still passes the laugh test. Most of the material is of more recent vintage: James Thurber, Peter Benchley, P.G. Wodehouse, Woody Allen, and Dave Barry.

This is the second time Damrosch has taught the course. The first was as an undergraduate seminar last spring that attracted so many applicants that Damrosch turned it into a lecture course. For the summer school version, he has edited the reading list, mercilessly eliminating material that failed to get laughs on the first go-round, regardless of its reputation or pedigree.

One casualty was the once-popular humorist S.J. Perelman.

“Perelman sank like a stone. He just left them cold. I don’t feel it’s my job to spend a week telling them why they ought to like Perelman.”

In addition to written humor, students view a selection of films that include the Marx Brothers’ “A Night at the Opera,” the fast-paced 1930s comedy “His Girl Friday,” Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove,” Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall,” the performance film “Richard Pryor Live!,” and the compilation of Monty Python skits “Now for Something Completely Different.”

The students also read a selection of theoretical writings, including seminal essays by Sigmund Freud and Henri Bergson. But Damrosch has no illusions that one theory can explain all humor.

“One of the fundamental themes of the course is that humor is extremely various. There’s no unified field theory of humor.”

Damrosch has not only eliminated the moldy humor of yesterday, he also draws the line at the other chronological extreme, excluding material he feels personally unable to relate to.

“If the students had their way, the entire course would be about ‘Seinfeld’ and ‘The Simpsons.’ But it’s not for me to tell them about ‘The Simpsons.’ I want to be able to get inside the material and feel I have a right to talk about it.”

Damrosch, 60, feels he is not the man to talk about that long-running send-up of the American nuclear family, and even less so about its more hard-edged offspring, “South Park.”

“I can’t relate to that all-embracing irony where you see through everything, you don’t take anything seriously, and you just chuckle at everything and move on.”

Damrosch’s taste runs more to the irreverent, boundary-busting comedy of Richard Pryor who can find devastating humor in the experience of a near-fatal heart attack.

“‘Richard Pryor Live!’ just blew them away. I was really surprised at how few of them were aware of his early work. That’s one of the great things about the course, being able to introduce them to things they might not have been aware of. It’s like making them a present of something they can really appreciate.”

In some ways, Damrosch seems an unlikely person to be teaching a course on the likes of Richard Pryor and Woody Allen. Born in the Philippines where his father was an Episcopalian missionary, he spent his early years unaware of the 1950s television personalities – entertainers like Milton Berle, Jack Benny, Sid Caesar, Lucille Ball, and Steve Allen – who formed the comic sensibility of most members of his generation.

As a scholar, Damrosch has specialized in the English writers of the 18th century, writing prolifically on most of the major figures of that era, including Samuel Johnson, Alexander Pope, Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding, William Blake.

But he has also branched off into other literatures, tracing the influence of such figures as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Goëthe on the development of the modern sensibility. His most recent book, “The Sorrows of the Quaker Jesus: James Nayler and the Puritan Crackdown on the Free Spirit” (Harvard University Press, 1996), explores the intellectual and religious significance of an obscure 17th century preacher. He is currently working on a biography of Jean Jacques Rousseau, the 18th century thinker whose writings have had such a profound impact on the modern temper.

So what is a scholarly heavyweight like Damrosch doing messing around with frothy effusions, wacky skits, and raunchy stand-up routines? Does this material somehow form part of an overarching scholarly project? Is Damrosch seeking to put the “lite” back in enlightenment?

The answer, in a word, is no.

“There’s really no bridge between the two,” he said. “I suppose you could say that a lot of the writers I’ve worked on were humorists, but I think I’ve just always been drawn to humor.”