SPH professor presents practical guide to living with germs

Staying healthy amidst bacterial ‘Overkill’

Scientists have shown that the kitchen sink – not the regularly scrubbed toilet – harbors the most fecal matter in the average home, carried there by unwashed hands after using the bathroom.

Use a tablespoon of bleach in a cup of warm water on the offending sink.

Another hot spot for fecal bacteria: How about your toothbrush?

Apparently, every time you flush, aerosolized particles from the toilet float as far as 6 feet away. So flush with the toilet lid down – and get a new toothbrush.

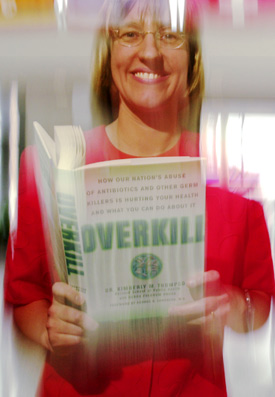

These and other occasionally disgusting facts about the way most of us live are featured in a new book by Harvard School of Public Health (SPH) Assistant Professor of Risk Analysis and Decision Science Kimberly Thompson. “Overkill: How Our Nation’s Abuse of Antibiotics and Other Germ Killers is Hurting Your Health and What You Can Do About It” (Rodale Press), written with health writer Debra Bruce, takes a look at how the way we live is causing the rise of drug-resistant germs that are threatening an abrupt end to “The Age of Miracles” and bringing us all into “The Age of Risk Management.”

Using bleach and closing the lid are just samples of the practical, everyday advice the book offers as alternatives to either getting sick and needing antibiotics or using the slew of commercial products labeled “antibacterial” that may only make the problem worse.

The Age of Miracles arose in the last century as new medicines and vaccines, coupled with a new understanding of the causes of disease, ended the everyday sway of scourges such as polio, diphtheria, measles, and rubella. The Age of Miracles is largely responsible for the dramatic increase in life expectancy over the last century: to age 80 for a child born in 2000 compared with 47 for a baby born in 1900.

Today, however, despite vast advances in medical knowledge and technology, drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis, staphylococcus, pneumococcus, and other germs are appearing with increasing frequency.

“That is a huge problem, and any book that brings to the lay public an awareness of antibiotic resistance is welcome,” said Donald Goldmann, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and professor in the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases in the School of Public Health who reviewed several chapters for Thompson.

Joseph Li, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and a doctor at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, said that not only have resistant strains of bugs become more common, but also the development of new, stronger antibiotics has slowed, making the battle against the stronger bugs tougher.

“The development of antibiotics has stalled and the bugs are getting smarter,” said Li, who also advised Thompson on the book. “The advent and discovery of antibiotics created a false sense of security and optimism.”

Thompson, an expert in health risk management, points the finger directly at us in assigning blame. Demanding the easy road to health is an American expectation. We don’t sit home in bed when we’re sick, we take a pill and go to work. Worse, when the kids are sick, we give them a pill and send them to school or day care – so that we can go to work.

The problem, Thompson writes, is that many times the pill doesn’t work. Many common ailments, from colds and flu to earaches, sore throats, and bronchitis, are caused by viruses not bacteria. And our modern antibiotics – so potent against bacteria – are useless against viruses. In 1992 alone, she says, there were 12 million antibiotic prescriptions written for upper respiratory tract infections and bronchitis, against which the antibiotics were most likely useless.

“The message to get out to patients is to keep an open mind and not to go into the doctor’s office demanding antibiotics – you might not need them,” Thompson said.

Even when we do take antibiotics for bacterial infections, we often stop when we feel better, before the prescribed course is completed and before all the target bacteria are killed, leaving the hardiest survivors to multiply.

When we’re healthy, we’re still making the problem worse. In the search for good health, we’ve snapped up anything with “antibacterial” on the label, spending $400 million yearly on antibacterial hand soaps alone.

“We need to wash our hands, but we don’t need antibacterial products every time we wash our hands,” Thompson said.

Thompson also points the finger elsewhere in society, to the doctors who buckle to patient pressure for antibiotics and the livestock industry, which relies on antibiotics to protect animals and make them grow faster.

Thompson’s book, which is aimed at the general public, presents this background and couples it with an extensive array of practical suggestions on how to live smarter with germs. In a chapter that deals with common ailments, Thompson describes illnesses, causes, what to do about them at home, and when to call a doctor. Her suggestions are founded in science, but expand beyond the bed-rest and plenty-of-fluid advice we all routinely ignore.

“The key is to be empowered and take charge of your own health and not to go overboard,” Thompson said.

Her suggestions also respect people’s preferences for conventional and alternative medicine. Those interested in some of the alternative strategies will find things like eating spicier foods for a cold (chili peppers contain a natural decongestant), eating cabbage for an ulcer (cabbage juice kills the bacteria Helicobacter pylori, which causes 90 percent of ulcers), and sucking zinc lozenges for a sore throat (some studies have shown that zinc boosts the body’s immune function).

Thompson provides a guide to safe handling and preparation of food – rare or medium-rare meat is risky – and highlights where different kinds of bacteria might be hiding in our homes – such as E. coli in the sink. She gives practical ways to fight harmful bacteria in the home and personalize one’s approach to controlling germs.

Acknowledging that the harried, modern adult can’t spend the day cleaning, Thompson points out hot spots in the home where targeted cleaning can make a difference. She cites sinks, doorknobs, faucet handles, garbage disposals, telephones, and your washing machine for special treatment.

Much of her advice is just old-fashioned hygiene: wash your fruits and vegetables, scrub your cutting board after using it for raw meats, and use bleach, which, despite the slew of fancy cleaning products on the shelves, is still a pretty good cleaner for almost anything.

In short, it’s better to take a few precautions and keep yourself healthy, than to rush to the doctor in the first place.

“What you need to do is develop good preventive practices and then use them,” Thompson said.