‘The paradox of American power’

Despite its dominance, U.S. can’t go it alone, says KSG’s Nye

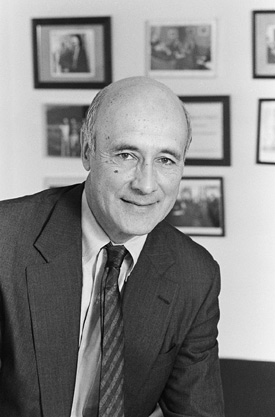

The United States is at a pinnacle of world power comparable to that reached by the British and Roman Empires, yet in today’s world its military might, economic power, and cultural sway aren’t enough to go it alone, according to Kennedy School Dean Joseph S. Nye Jr.

“We’re going to find that being No. 1 is not going to be enough to protect us,” Nye said during a recent interview.

The world’s globalized economies, near-instant communications, the World Wide Web, and the global reach of problems such as terrorism, global warming, the extinction of species, and the AIDS epidemic amply illustrate that no one nation can take on these problems alone.

Though no one nation can tackle these problems alone, the United States is in a unique position to provide global leadership into the foreseeable future.

Nye said the United States today wields two kinds of power, both of which are critical to America’s predominance on the world stage. Nye defines “hard power” as military or economic strength, because either can be used to persuade other nations to do our will.

“Soft power” is a bit fuzzier. It consists of the attractiveness of our culture, the strength of our ideals, and willingness of other nations to adopt those ideals or to follow our lead because of our moral authority or the rightness of our cause.

The strength of America’s soft power can be seen today in the spread of popular music, blue jeans, and other American fashions. It can be seen in the way American-made movies and television programs are seen around the world. It can be seen in the adoption of democratic governments in countries around the world and in the way other nations look to the United States to protect freedoms and human rights.

The two types of power make a potent combination, Nye says, that if managed wisely, can assure America’s place at the center of the world stage for decades to come. What that means, however, is acting multilaterally – after consultation with friendly nations or through international organizations – whenever possible. It means reserving unilateral action, particularly unilateral military action, for those instances when critical national interest demands it.

Nye, who served as assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs in the Clinton administration, laid out his argument in a recent book, “The Paradox of American Power: Why the World’s Only Superpower Can’t Go It Alone.” The book, published this year by Oxford University Press, has already been released, but has an official publication date of March.

Nye wrote much of the book during a mini-sabbatical last spring at Oxford University. The book was mostly completed when the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks took place. While such dramatic events required him to revise parts of his book to reflect the new world circumstances, the tragedy also served to highlight Nye’s central argument. Even though terrorists struck a terrible blow on American soil, international cooperation is required to root out an organization that has tentacles flung across the globe.

Nye wrote the book as a follow-up to his 1990 book, “Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power.” In “Bound to Lead,” Nye said he sought to puncture what was then a popular view that American power was in decline. Nye then pointed out that as the world’s only remaining superpower, the United States was uniquely suited to lead.

Nye said he decided then to re-examine the conventional wisdom in another 10 years. The result is “The Paradox of American Power.” American power waxed, rather than waned during the 1990s, as Nye predicted, but today many people think America is so far ahead of its closest rival that it can do essentially what it pleases on the world stage.

That’s not the case, Nye says. In a recent interview in his Kennedy School office, Nye gave the new Bush administration mixed marks in its work so far. While the military action in Afghanistan has been successful, enhancing our hard power, the Bush Administration’s go-it-alone approach to dealing with the problem of global warming by rejecting the Kyoto Accords and announcing its intention to withdraw from the 1972 Antiballistic Missile Treaty, as well as other instances when the Bush Administration has turned its back on European and other allies, has hurt our soft power.

Already there is grumbling among European and other nations about Bush’s statements during the State of the Union speech about the “axis of evil”: Iran, Iraq, and North Korea. Unilateral military action against any of those countries would certainly draw less support than the U.S. action in Afghanistan.

Nye laid out a policy blueprint that means consulting allies, taking advantage of international agreements, and acting through international agents such as the United Nations and the World Trade Organization whenever possible. It means protecting international resources, promoting free trade, mediating disputes and promoting economic development. And it means making difficult distinctions for humanitarian action and in regional conflicts: acting in true cases of genocide, staying clear of civil wars of national determination, and deferring to regional allies who may have more at stake.

Nye’s suggestions center, ultimately, on a careful balancing of U.S. interests in both the short and long term, on the needs of the international community and on an awareness that neither the scourge of international terrorism nor the inevitability of global warming is going to go away through the actions of the United States alone.

“Countries are going to need to turn to international institutions to deal with problems that globalization is putting on the table,” Nye said. “These are not problems that one country can solve on its own.”