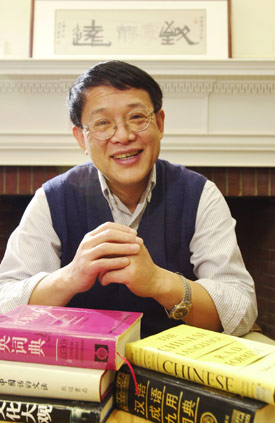

Bringing Chinese to life

Baozhang He says speaking is as important as reading

Baozhang He is trying to change the way Chinese is taught and learned in the United States.

In the past, Chinese was taught by rote – that is, by translating English into Chinese and then memorizing through mechanical drills. Today the emphasis is on living language, using Chinese in conversation rather than “repeating after me.”

“Language is not like math when you can just get the structure right or wrong,” He said. “You can’t just get the grammar and then get reading and writing.”

He, appointed professor of the Practice of Chinese Language last July, directs the Chinese Language Program in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, aims both to dispel stereotypical notions about the teaching of Chinese and to professionalize the field.

Too often, he said, people assume if someone can speak Chinese, they can teach it. Though knowledge of Chinese is obviously critical in being able to teach, so is some teaching ability, He said. Chinese presents its own set of problems to students, who must not only master the spoken language, but also the written language with its thousands of characters. He said a student can do well learning just 4,000 characters, but the written language is complex enough that reading street signs can be quite a task, even for more advanced students.

“In the field, they still have the older notion that if you are Chinese, you can teach Chinese,” He said. “We want to promote teaching Chinese like teaching English as a second language, as a field with research and training.”

Different levels, impossible situation

Chinese is growing in popularity in the United States, He said. More high schools and colleges offer courses in the language, and scholars, who used to learn to read and write Chinese but who had little speaking ability are now learning to speak as well.

“New scholars can communicate with people in Beijing and Taiwan and they can also read and write,” He said.

Here at Harvard one of the teaching problems is the classroom mix of students with different backgrounds in Chinese, He said. Some are complete novices, while some have had some Chinese in high school. Still others, he said, know Chinese because it was spoken in the home, even though they’ve never taken a class.

Professor of Chinese History Peter Bol, chair of the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, said He has tackled that problem by designing different tracks for the different students. Students with some speaking knowledge of Chinese, such as those who speak it at home, can take an accelerated course where they can complete in one year what the track for those with no experience would do in two years.

Students wanting to learn faster can take an intensive program where, like the accelerated program, two years’ worth of material is covered in one year. Rather than being covered faster, more time is allotted for class.

“We have, when we teach languages, a clientele with different levels of competence – some with a family background, some with a little high school background. If you put them in with students coming in cold you create an impossible situation in the classroom,” Bol said.

Bol said He has also led the way in using information technology to teach Chinese and is working to develop Web sites that address different problems students might encounter so the students can seek individualized help on the Web for their particular difficulty.

Another concern in the field is that textbooks from China may not be appropriate for American students, Bol said. He has helped fill that gap by writing textbooks for advanced and advanced beginning students.

From farmland to Disneyland

He’s road to Harvard started with a leg injury on a farm two hours outside his native Beijing. When He was in high school, China’s Cultural Revolution was still under way. Rather than going to college as he had wanted, He was sent to a farm outside Beijing until he hurt his leg.

“As a city kid not knowing how to farm, I injured my leg and got sent home,” He said.

Once back in Beijing, one of his relatives began teaching him English while he recovered. When the Cultural Revolution ended after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, He applied to college, taking entrance examinations in teaching English. He was accepted to the Beijing Languages Institute, where he received a bachelor’s degree in 1982.

Before he received his degree, however, He was told to act as a translator for a Disney film crew in China to film “Wonders of China,” a 360-degree movie on China’s natural beauty intended for screens at Walt Disney’s theme parks. So, for two years, He worked on the project, traveling around the country and learning about the film industry from behind the scenes.

After his experience with Disney, He was asked whether he wanted to work in films in China, but he decided to return to language teaching and took a post teaching English in the Beijing Languages Institute, where he was an assistant lecturer in English from 1982 to 1983.

In 1983, He left China for Ohio, where he began working on a master’s degree in Chinese linguistics at Ohio State University. He received his master’s in 1986 and a doctorate in Chinese linguistics from Ohio State in 1992. Since then, he has taught at the University of Michigan, Middlebury College, and Indiana University before coming to Harvard in 1992 as a preceptor in Chinese and acting director of the Chinese Language Program. In 1996, He was named director of the Chinese Language Program and senior preceptor in Chinese.

“We study how we can best present Chinese to our American students,” He said. “I would think we will be one of the best and strongest [programs] in the nation.”