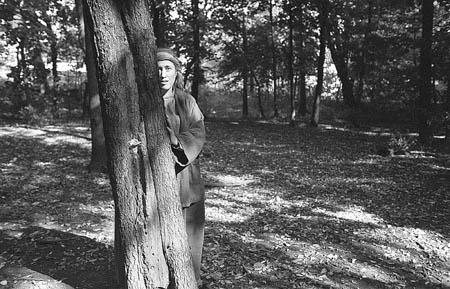

Writer Greer Gilman creates her own world

The Big Picture: A snapshot of the Harvard Community

If you like a challenge, you’ll love the work of Greer Gilman.

A writer whose book “Moonwise” won the Crawford Award for the best first fantasy novel of the year in 1991, Gilman sets all her stories in the same imagined world, called Cloud.

“Cloud has the same root as clod; it’s hill,” she says. “So what you see in the sky are metaphors up there. And I think the doubleness of the language is important to me.”

Important may a bit of an understatement. Double and triple meaning, archaism, synecdoche, equivoque, dialect: you name it, if it’s a kind of wordplay, it probably figures into Gilman’s darkly atmospheric prose poetry with a decidedly folkloric bent. Here’s a sample from the short story “Jack Daw’s Pack”:

“In a game, triumphant, he plucks out the Crowd of Bone, or Brock with her leathern cap and anvil, hammering at a fiery heart, a fallen star. (It brock, but I mended it.) Death’s doxy, he calls her, thief and tinker, for she walks the moon’s road with her bag, between the hedges white with souls; she takes. Here’s a lap, he says, in his shawm’s voice, sharp with yelling out for ale.”

In Gilman’s world a crowd is a fiddle, a chimney sweeper’s a dandelion, and a laithe is a barn. Words such as kist and clagg, rantipole and crowdy, flyte, and thrawn are not uncommon.

“As soon as I discovered there was an OED [Oxford English Dictionary],” she says, “I started reading it. I like words. They’re almost the particle physics of narrative.”

Not what you might expect from a woman who grew up in a rural southeast Connecticut town that bore her name. “Pretty much nobody lived in the village but my family,” she says of tiny Gilman, population “I don’t know, under 100.” But the pastoral setting fed the spirit of this idiosyncratic only girl in a family of four. “I was very, very fortunate in that we lived in the woods,” she says, “and there was no worry in those days about letting children wander around on their own.”

The downside, she notes, is that “the schools were not very good.” But because her parents always made sure she had books, she became “pretty much an autodidact,” ending up with a B.A. in English from Wellesley and a master’s in the field – “Renaissance stuff” – from Cambridge University in England. Since 1985, she has worked at Widener Library, where she is now a forensic librarian and cataloguer in preservation, though she prefers to think of herself as “sort of a utility outfielder in odd languages and classics.”

Gilman became interested in England’s North York Moors because she liked the area’s folksongs and dialect, and says this “wild, bleak, hilly, desolate” region has shaped her language. And, as in all fiction, her language shapes her stories. “Once you’re in a myth,” she says in an interview published in the winter 2000 issue of Century, “there is no out of order: only variations on a stated theme. The art of fugue. Cat’s cradles.”

According to reviews posted on Amazon.com, her readers – every one a puzzle lover – typically return to “Moonwise” year after year, getting something new out of it each time. “It is both like interpreting a dream and unearthing precious jewels” is a typical sentiment, as is “it speaks in the language of the subconscious and racial memory.”

“Dreamlike” is perhaps the most accurate description of Gilman’s ethereal universe. “Damned if I can write a linear narrative,” she concedes in the Century interview. And her readers wouldn’t have it any other way.

We serve the public interest! Interesting people, interesting jobs, interesting hobbies – we want them in the Big Picture. If you have an idea for the Big Picture, give us a buzz at big_picture@harvard.edu