Summer of study

GSE interns teach at Cambridge-Harvard Summer Academy

Summer school occupies one of the darkest chambers of high school’s hall of horrors. There’s the shame of having failed a class – or several – during the year, the agony of waking up early and going to school on beautiful summer days, the ache of spending sultry evenings with homework assignments instead of with friends.

For 170 Cambridge high school students, however, Harvard has helped take the sting out of summer school. “It’s been great,” says Ramon Trinidad, 17, a student at the Cambridge-Harvard Summer Academy at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School. “I’m actually glad I came to summer school.” While not all students share Trinidad’s unabashed glee, he’s certainly not alone.

The Cambridge-Harvard Summer Academy represents a five-year, $1 million commitment of Harvard resources to public education in the city of Cambridge, made by former President Neil L. Rudenstine in May 2001. Harvard’s involvement has enhanced the summer school program for Cambridge public school students by increasing the teacher-student ratio 80 percent and expanding the program from four weeks, four days per week to five full weeks.

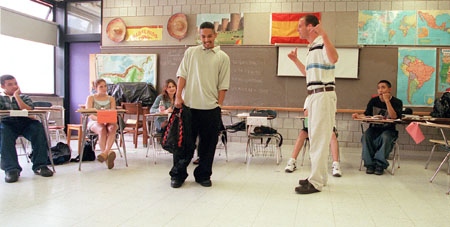

The sugar-coating on the bitter pill of summer school, say participating students, teachers, and administrators, is the Summer Academy’s luxuriously low student-to-teacher ratio, made possible by 40 intern teachers from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education (GSE). The interns work side by side with 10 mentor teachers in math, language arts, and social studies classrooms of students of varying grade and achievement levels.

“It’s impossible to slip by,” says Summer Academy principal Frank Honts, acknowledging that slipping by during the school year is what landed many of the students in summer school to begin with. “The whole process of learning is much more individualized, and kids are being held more accountable.”

With courses structured to emphasize core learning skills, like writing an analytical essay, this individualized approach helps students succeed where they once struggled. “They’re bright and articulate. Conceptually they can do a lot, but when it comes to the structure of writing, they have trouble,” says mentor teacher Damon Smith. His social studies class has been studying the Aztecs; one assignment is to write essays on the impact of the Spanish on the Aztecs of Mesoamerica.

Brendan McGurk, the GSE intern who leads the essay-writing class (Smith’s interns take turns at the helm), helps the students understand the structure of an analytical essay: a thesis, supporting information, and conclusion. “It’s about writing down an argument,” he says of the thesis. McGurk splits the class into teams of three, then he, Smith, and the other interns work closely with the students as they help each other structure their essays. As a student fidgets and protests, unable to escape the teacher’s persistent attention, intern Jennifer Lyders reminds him, “This is supposed to be work.”

Across the hall from Smith’s social studies class, mentor teacher Jed Lippard works with another small group, this one slightly older and seemingly more focused. Momo Chang, Casey Allison, and Mangai Arumugam are intern teachers from the Graduate School of Education; the Cambridge-Harvard Summer Academy and related course work are their introduction to the GSE and, for some of them, to classroom teaching.

Like McGurk and Lyders, they have jumped headlong into the challenges of teaching, working with academically at-risk groups of urban teens, some of whom are nearly twice their size and have attitudes even larger. But mentors such as Lippard and Smith give support to the interns with a safety net of guidance and feedback. The Cambridge-Harvard Summer Academy is structured to provide the Harvard students with as rich a learning experience as their teenage charges are receiving. Interns and mentors split their mornings between teaching and two-hour planning and review sessions; in the afternoons, interns take courses at the GSE.

“It’s a very intense program,” says Chang, who worked as an AmeriCorps volunteer in a high school in California but had not done classroom teaching before. “It’s a really good opportunity for people who haven’t taught before.” This fall, Chang will return to Cambridge Rindge and Latin School for her student teaching; she looks forward to seeing some of the students from her summer school class.

Mentor teachers like Lippard do double-duty teaching, first in the classroom and then in the small groups of interns. As an experienced teacher, he sees the benefit of a program like the Summer Academy quite clearly. The student-to-teacher ratio is “a tremendous luxury,” he says. “In five weeks, we’ve gotten to know these kids better than any teacher’s gotten to know them before.”

Certainly, summer school students are expected to master the social studies or language arts they set out to learn in July. But the Summer Academy seems to be meeting a more elusive goal: with its small classes and individual attention, it’s helping students learn to succeed. “A lot of these kids have been conditioned to fail in school,” says Lippard. “We’re creating an expectation of success.”

Ramon Trinidad is one of them. “This summer school will help me a lot during the year,” he says, admitting that he failed courses this past year because he was lazy. “It’s making me develop a way that I can do my homework.”

“I think I learned more this summer than I learned in the entire year,” says Bobby Normil, 16. “I actually read a book. I haven’t read a book since seventh grade.” Normil, who will pass both his summer school courses with A’s, has been encouraged to take advanced placement courses when he enters 11th grade next year. “I’m a fast learner, but I’m lazy,” he says. “This experience was different.”

Katherine Merseth, director of the Teacher Education Program at the GSE, agrees. “This is a very special opportunity for the kids to really make some tremendous academic gains,” she says, noting that there’s anecdotal evidence, at least, that the summer school students are succeeding. “Exposing the high school kids to young, enthusiastic teachers is a real shot in the arm.”

Merseth has structured the Teaching and Curriculum program at the GSE so that more student teachers will work in urban schools in Boston and Cambridge. “These young people are idealistic and bright and they’re well-equipped to do this,” she says of the GSE students. Their commitment to educating urban students “is huge,” says Merseth. “That’s going to carry them a long, long way.”

On the last day of the Summer Academy, after their classes have ended but before a celebratory barbecue, the students gather in the high school media cafeteria for a closing ceremony. A parade of luminaries at the podium drives home the importance of this enhanced summer school experience. Principal Honts, Merseth, Cambridge School Superintendent Bobbie D’Alessandro, Cambridge Mayor Anthony Galluccio, and Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers each congratulate the students on their achievements.

“Harvard and Cambridge are natural partners,” says Summers after speaking with several students about their educational experiences. “Harvard needs to do everything it can to make Cambridge schools the best they can be.” Drawing on his background as an economist and his experience as secretary of the treasury, Summers impresses upon the students that nothing will have a larger impact on their future lifestyles and earning potential than their level of education.

“I hope and I trust that we will see some people in this room at Harvard,” Summers says. The cheers in the room indicate that some of the summer school students share his hope.

Contact Beth Potier at beth_potier@harvard.edu.