Translating the Renaissance

Texts by Boccaccio, others, are available in English for the first time

James Hankins wants to raise a sunken continent.

We are not talking about physical geography here, but rather a continent of the mind, a vast literary landscape that has become, through a quirk of history, invisible to all but a few scholars.

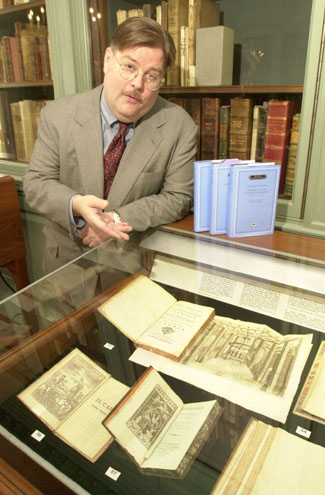

The substance of that lost continent is a vast collection of literary works composed in Latin between the 14th and the 17th centuries. The means with which Hankins plans to raise that sunken mass and bring its contours to light is a new publishing venture called The I Tatti Renaissance Library. Hankins, a professor in the History Department, is the general editor of the series.

“This is a literature that is important to the study of Western civilization, but until now it’s been very hard to find. It’s dropped out of sight, but not because it’s not great stuff,” Hankins said.

The I Tatti Renaissance Library will make this literature, which up until now was only accessible to a small group of specialized scholars, available to all.

To illustrate the impact this initiative will have, Hankins mentions one of the three works that will inaugurate the series – the first volume (books I-IV) of “Platonic Theology” by Marsilio Ficino. Ficino lived in Florence in the 15th century, where he received the support of the de’ Medici family. He was responsible for reintroducing the study of Plato into Western culture. “Platonic Theology” is an attempt to reconcile Plato with Christianity.

What is so significant about Ficino is that his work influenced many Renaissance artists, Michelangelo and Botticelli among them. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescos and Botticelli’s “Primavera” are thought by many scholars to reflect Ficino’s Neoplatonic ideas. Yet, up until now, there has been no English translation of this, his principal work.

The other two works appearing this spring are equally important to the study of Renaissance culture, and, like “Platonic Theology,” have never before appeared in English.

“Famous Women” by Giovanni Boccaccio, the first collection of biographies devoted exclusively to women, influenced the work of many other writers, including Geoffrey Chaucer. Today, Boccaccio’s “Decameron,” which he composed in Italian, is still well-known, but “Famous Women,” along with his other Latin works, is all but forgotten.

The same is true of “History of the Florentine People” by Leonardo Bruni. Famous in his day as a translator, orator, and historian, Bruni was the best-selling author of the 15th century. His “History of the Florentine People” in 12 books (the first volume will present books I-IV) is generally considered the first modern work of history.

How is it that works of this magnitude have never been made available in English translation? The answer has to do with the vagaries of intellectual currents and with politics. Latin, which was once the lingua franca and literary language of educated Europeans, began to fall out of favor after the 17th century as the spirit of nationalism placed greater emphasis on the vernacular tongues.

Later writers dismissed these Neo-Latin works as stilted imitations of classical authors like Virgil and Cicero, but in fact they were much more than that.

“The Romantics had a strong prejudice against Neo-Latin literature because they were strongly nationalistic, but most Renaissance writers believed that they needed both Latin and the vernacular. At that time, there were no grammars or dictionaries for vernacular languages like Italian. There were also numerous dialects. Latin gave writers a standard of elegance and precision,” Hankins said.

While Renaissance humanists studied the great classical writers assiduously and strove to imitate them, many, like the Dutch scholar Erasmus, urged his contemporaries to write Latin in their own distinctive voice.

Nor was writing the only thing Renaissance humanists used Latin for. It was also a spoken language, employed by diplomats, orators, and teachers. Much as Yiddish once united Ashkenazi Jews, Latin allowed men and women from the far points of what had once been the Roman Empire to converse and correspond with one another.

Although the fellowship of Latin was a largely male world, women were not barred from it. Queen Elizabeth I spoke Latin fluently and took delight in scolding male ambassadors who assumed she would need an interpreter to understand them.

Far from being stilted, Neo-Latin prose and poetry, in the hands of a skilled practitioner, could be a powerful medium of expression for the most personal of thoughts and feelings.

“Sometimes Renaissance authors will say things in Latin they wouldn’t say in the vernacular,” Hankins said. “I think it’s because it reminds them of their school days. There’s a certain intimacy about it.”

John Milton, for example, chose English for his poem “Lycidas,” an elegy for Edward King, a young clergyman whom Milton scarcely knew.

“But he wrote a Latin elegy for Charles Deodati, who was a much closer friend – and it’s a more passionate poem,” said Hankins.

The new series, sponsored by the Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies at Villa I Tatti near Florence, is published by Harvard University Press (HUP). Modeled on HUP’s famous Loeb Classical Library, which began publishing in 1912, the I Tatti books will feature the Latin text on the left-hand page and the English translation on the right.

Founded by James Loeb, Class of 1888, the Loeb Library is distinctive for its colorful bindings (green for Greek, red for Latin) as well as for the small size of the volumes. They were originally designed as “handy books of a size that would fit in a gentleman’s pocket.”

In addition to their handsome blue bindings, the I Tatti books differ from their models in size. At 51/2 by 81/4 inches, they are too big for all but the largest pockets. But there is a good reason for this.

“We talked to all the Loeb editors, and the first thing out of their mouths was, do a larger format. The small size makes it hard to include maps, and when you print long lines of poetry they tend not to fit on the page,” said Hankins.

Hankins describes the size that was chosen as “a small octavo,” a format that was invented, appropriately enough, by a Renaissance printer named Aldus Manutius. It was a size developed especially for travel, if not in a pocket, then in a trunk or suitcase.

At $29.95 per volume, the books will not be featured as impulse-buy items alongside bookstore cash registers, but the cost is far lower than that of many specialized scholarly volumes and should have a significant impact on the teaching of Renaissance subjects.

“The main purpose of the series is teaching Renaissance studies,” said Villa I Tatti Director Walter Kaiser. “It means that professors can actually assign these works. It should make a huge difference in the field.”

According to Kaiser, between 15 and 20 more volumes are now in the pipeline. He hopes that there will be three or four new titles appearing each year.

“My dream is to see 150 to 200 volumes of Renaissance Latin literature on the shelf, just like the Loeb Library,” said Hankins. “Then we’ll be able to see the contribution of Neo-Latin literature as a whole.”