Rudenstine’s journey to Harvard began at 14:

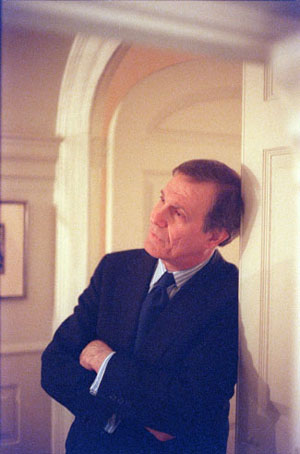

This is the first in a two-part series on Neil L. Rudenstine, who will conclude his 10-year tenure as Harvard’s 26th president on June 30.

At the age of 14, Neil Rudenstine set out on an epic journey. Physically, the distance was only a few miles, but in personal terms it was like traveling to another world.

He had attended local public schools through the eighth grade. Now he was about to enter the Wooster School, a private, college-preparatory institution. Although it was located in Danbury, Conn., his hometown, he would live at the school rather than at home. It was not a turn of events that anyone in the Rudenstine family had anticipated.

“We really didn’t know what a boarding school was,” Rudenstine said, “and we certainly had never heard about Wooster. It was also incredibly expensive. It would have cost practically my father’s whole salary to go to the Wooster School for one year.”

Rudenstine was able to attend the school because he had won a full scholarship, a distinction that created its own set of burdens.

“Academically, I wasn’t at all sure I would survive because it was a very selective school, and it was totally different from anything I’d ever been in before. And because I was going on a full scholarship, I felt that … no one had actually told me this – but I felt that I certainly had to do well.”

Rudenstine was not only the first person in his family to go to boarding school; he was the first person in his immediate family to finish high school, period. In that sense, he was a social and educational pioneer, an exciting position to be in, but a scary one as well. It meant that, in some areas at least, he could no longer turn to his parents for guidance or advice.

“I think that must be an experience for many people who are the first ones in their family to go to private school or college, because it’s a world that hasn’t been penetrated. It wasn’t as if you could turn to your father and say, ‘How was it?’ and he would say, ‘It’s nothing to worry about.’”

While Rudenstine’s parents were unable to give him the inside scoop on the prep school experience, they were a major influence on his getting into one in the first place. His father, Harry Rudenstine, never went further than the eighth grade, but he was a voracious reader who instilled dreams of educational attainment in his children. A first-generation American, the son of Jewish immigrants from Kiev, he joined the Army Corps of Engineers as a young man, learning trigonometry and other skills on the job.

It was while he was stationed in Ossining, N.Y., that he met his wife, Mae, an Italian Catholic whose family had emigrated from Campobasso, a town just east of Naples. As a member of the Corps, Harry traveled extensively, but after he and Mae were married, a more settled lifestyle seemed in order, so he got a job as a guard in the federal prison system. More moves followed, but mostly within the Northeast. The last assignment brought the family to Danbury, where a new federal prison had just been built.

“My father was very thoughtful, very interested in education; read tremendously, especially history and biography. I think if he had gone to college, he would have had an extraordinary career, and he made up for it by reading on his own and by being very powerfully concerned that his children should be well educated.”

Rudenstine did do well at the Wooster School, well enough to be admitted to Princeton, again on a scholarship. But Wooster was far more than a stepping stone to the Ivy League. Founded in 1926, the school, at the time Rudenstine arrived, had only 90 students who convened as a group several times daily – for meals, chapel, evening study hall, and athletics. Rudenstine later was to describe it as almost a one-room schoolhouse. But what the school lacked in size, it made up for in the quality of its faculty, particularly its headmaster, John Verdery.

In 1954, responding to the Supreme Court decision Brown vs. The Board of Education, Verdery decided to integrate the school, although, as a private school it was not legally bound by the court’s verdict.

“It had a real effect on me to see him decide to integrate this little boarding school when nobody was pushing him to do so,” said Rudenstine, who graduated in 1952, but continued to keep in close touch with the school. “In fact, a lot of people didn’t think he ought to do it, but he just felt it was the right thing to do.”

Rudenstine describes his experience at Princeton as “wonderful,” although his four years there did not give him a specific career direction. He chose an interdisciplinary major called Special Program in the Humanities and wrote a senior thesis on the poetry and criticism of Keats, Arnold, and Eliot. He also took history courses and thought about becoming a lawyer, but winning a Rhodes Scholarship meant that he could defer his final decision for another two years.

For a young man who had never been out of the United States, New College, Oxford, was a revelation. Rudenstine sailed to England with several dozen other Rhodes and Marshall scholars, an interlude that allowed the group to get to know one another and form friendships.

A mere 11 years after the end of World War II, England was still recovering from the damage inflicted by German bombing, but at the same time there was an exciting sense of rebirth. Rudenstine benefited from the presence of such distinguished professors as Isaiah Berlin, George Kennan, and W.H. Auden. He also took full advantage of the opportunity to see Europe.

“In those days, the dollar was very strong and Europe was very inexpensive, so a student with very little money could still travel. I would zoom off with two and three friends to one vacation in Scotland, more than one in France, more than one in Italy, one in Salzburg, and so on. You could live in youth hostels or inexpensive hotels and eat modestly on a few dollars a day.”

Rudenstine started out studying modern history, then switched to literature, necessitating his staying an extra year to complete his studies. It was during this time that a friend invited him to tea and introduced him to a young student named Angelica Zander.

The daughter of a Dutch mother and a German-Jewish father who had left Berlin in 1937 and settled in London, Zander was working on a bachelor’s degree in modern languages and literature at the time. The relationship evolved gradually, but by the end of Rudenstine’s third year at Oxford the couple were well along the way to being a couple for life.

They were not alone. Three friends – Americans who had sailed to England with Rudenstine and studied with him at New College – also married English women. The four couples remain friends to this day.

Rudenstine made another important decision at this time. He finally gave up all thought of a law career, deciding instead to go to graduate school in English literature. He applied to Harvard and was accepted, arriving here in September 1960, after six months spent fulfilling his ROTC obligations as an artillery lieutenant at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.