The economics of ‘creative destruction’

Aghion talks about the power of entrepreneurs

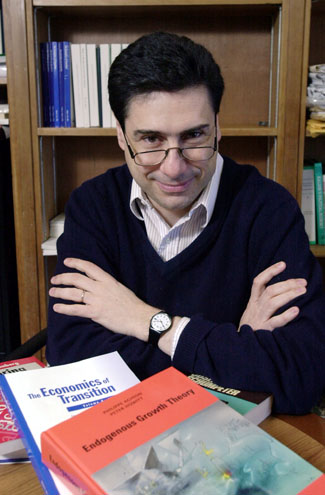

As an idealistic young student in Paris, Philippe Aghion dreamed of making the world a better place, of reducing inequality and environmental damage, and of taking better advantage of technological progress to reduce poverty and illiteracy and increase social well-being.

The path he chose to achieve this end was economics, the science of allocating scarce resources to meet human needs.

What progress has Aghion made toward realizing those early ambitions? “Well, it is very slow,” he admitted. But the obstacles he has encountered have not dampened his enthusiasm or sapped his energy. At the age of 44, Aghion is one of the most prolific and influential economists of his generation. He was appointed July 2000 to a tenured position in the Economics Department in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

“We are delighted and excited about the appointment of Philippe Aghion,” said Oliver Hart, the Andrew E. Furer Professor of Economics and chair of the Economics Department. “He is a world leader in applied theory, having done pioneering work in both contract theory and growth theory. He will be a great addition to the department.”

Aghion focuses much of his attention on the relationship between economic growth and institutions. He has reintroduced into growth theory the concept of “creative destruction,” first formulated by economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950). According to Schumpeter, entrepreneurs are constantly looking for new ideas that will render their rivals’ ideas obsolete. Thus by creating something new, successful innovators destroy the profits that motivated their predecessors.

By focusing explicitly on innovations as a main source of economic growth, this approach opens the door to a deeper understanding of how organizations, markets, trade, competition policy, the financial system, property rights, and the legal framework, both affect and are affected by growth by motivating entrepreneurs to engage in innovative activities.

With his co-author Peter Howitt from Brown University, Aghion has used his Schumpeterian growth model to fit the far more complex and high-powered economy of today in which technological innovation and globalization have accelerated the process Schumpeter first identified. Their approach is elaborated in the book “Endogenous Growth Theory” (1998, M.I.T. Press).

“We were building on the framework that Schumpeter created. We wanted to put him back into the mainstream of economics,” Aghion said.

Aghion has focused particularly on industrial organization and contract theory when asking the question of how to design institutions that foster innovation. Free enterprise cannot do the job by itself, he believes. Rather, what is needed is a finely tuned balance between business and government, between markets and legislations.

“What the market will not do is prevent powerful incumbents from barring entry to new innovators, in particular by lobbying governments to introduce administrative procedures, taxes, trade barriers, and regulations to oppose further technical progress.”

In other words, it is in the interest of successful innovators who displace older entrepreneurs to ensure that they are not themselves displaced by the next generation. They may use their dominance in the market to keep new ideas from reaching the public, or they may influence lawmakers to pass legislation favorable to themselves. Preventing such a situation is the aim of anti-trust laws and of political constitutions aimed at circumventing vested interests.

On the other hand, entrepreneurs must be able to profit from their innovations. Creative destruction may be inevitable, but it must not be achieved too easily, or innovators will not have enough incentive to enter the market. Ensuring that innovators profit from their innovations is the object of patent laws and intellectual property right legislations.

“You want patent protection, but you also want anti-trust laws – both are important. It’s not an easy balance to strike,” Aghion said.

In the process of trying to link growth and institutions, Aghion has also contributed to the field of contract theory and corporate governance. His work concentrates on the question of how to allocate authority and control rights within a firm, or between entrepreneurs and investors. In the latter case the tension is between entrepreneurs, who want investors to keep pumping money into their projects, and wary investors who may want to pull the plug and cut their losses.

For example, previous attempts to resolve the tension between entrepreneurs and outside investors have focused on the comparative incentive effects of standard debt and standard equity, both of which were merely seen as different ways of sharing monetary revenues between the two sides. But Aghion has taken a different approach to financial structure, concentrating on how different types of financial instruments can result in different control allocations between the two parties.

In addition to his academic research, Aghion has been associated with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) since 1990. The organization, based in London, seeks to help the 27 countries of the former Soviet Union and the Soviet bloc nations manage their transition to a market economy.

Aghion continues to serve as research consultant for the EBRD and as a managing editor of the journal The Economics of Transition, which he launched in 1992. He has participated in the creation of an extensive enterprise survey on transition economies and in the publication of an ongoing series of reports and research papers.

“It’s the first time we have been able to collect enterprise data on such a large scale. The project will enable us to compare the progress of firms and industries across these 27 countries as they undergo institutional change. It is like an enormous laboratory which will allow us to analyze the effects of institutional change on economic growth and development.”