Some don’t like it hot

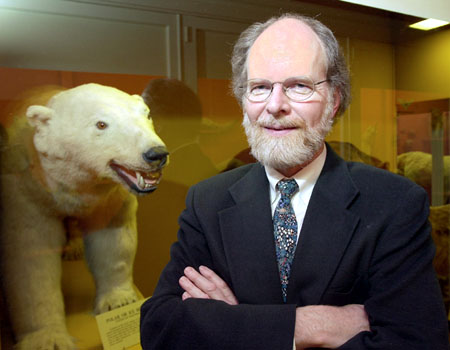

James McCarthy knows what’s around the corner

A 1999 study of polar bears on Hudson Bay showed that rising temperatures are thinning the pack ice from which the bears hunt, driving them to shore weeks before they’ve caught enough food to get them through hibernation.

One of those trying to give the polar bears a break and settle the argument is James McCarthy, Alexander Agassiz Professor of Biological Oceanography and an internationally known authority on climate change. McCarthy was among a handful of top scientists who coordinated a remarkable report by the world scientific community this year that said global warming is real, it’s here, and it’s going to be worse than we thought.

“We already see effects that [indicate] the change in climate has occurred,” said McCarthy, who also serves as director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, head of the concentration on environmental science and public policy and Pforzheimer House master. “And the projection of some of those [effects] into the future are not a pretty scene.”

McCarthy co-chairs of one of three working groups of the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a body established in 1988 to gather information on human-induced changes to global weather. Since its creation, the IPCC has released three assessments.

The Third Assessment Report was released in three parts over the past three months and states more clearly than ever that global warming is occurring. It also states for the first time that the evidence is overwhelming that humans are causing most of the change.

The report comes against a backdrop of international disagreement over how to curb rising levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, largely carbon dioxide.

The United States and Europe are at odds over details of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which provides guidelines for the reduction of greenhouse gases. Opponents of the treaty, which has not been approved by the U.S. Senate, argue that it hurts developed nations and would limit economic growth in the United States.

President Bush added fuel to the debate this month and infuriated environmental groups when he announced he would not fulfill a campaign pledge to impose mandatory carbon dioxide reductions on power plants.

Atmospheric carbon dioxide slows the rate at which heat radiated by the Earth is lost to space. Carbon dioxide is a naturally occurring gas that is released and absorbed in a natural cycle. One illustration of that complex cycle is that animals, such as human beings, exhale carbon dioxide, which is absorbed by plants. The plants use the carbon dioxide and then release oxygen that humans can inhale.

Fossil fuels release carbon dioxide when they’re burned, throwing the natural cycle out of balance and increasing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The Third Assessment Report’s release gained worldwide media attention and prompted speculation about such effects as the flooding of tropical islands, the flow of refugees from agricultural failure into Europe from Africa, and the disappearance of species that depend on specialized environments.

Tropical impacts

The report of Working Group II, which McCarthy co-chairs, talked about the potential impacts of projected global average temperature increases between 1990 and 2100 – which are expected to be in the range of two and a half to ten degrees. This four-fold range reflects varying future scenarios with different human populations, standards of living, and levels of environmentally-friendly energy sources.

The Working Group II report, released in February, painted a picture of tropical farmers unable to grow crops, a spread of tropical diseases such as malaria and cholera, and an increase in flooding from both heavy rains and rising seas.

One of the expected hallmarks of climate change, however, is its lack of uniformity. Talking about rising average temperature is almost misleading, McCarthy said, because the effects will vary in different parts of the world. Common all over, however, will be the increase in violent storms and extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, as the atmosphere seeks to redistribute the new energy in the form of heat that it is absorbing.

Other major global shifts, such as changes to ocean currents, are less likely but possible. Should they occur, they could also have far-reaching effects. If the warm water current that flows across the North Atlantic were to slow or shift south, for example, temperatures in Europe, which typically experiences warmer temperatures than its northerly latitude would indicate, could plunge. Great Britain and Ireland, for example, are at about the same latitude as the southern tip of Hudson Bay, though their temperatures are much warmer. New England, by contrast, is at about the same latitude as the northern Mediterranean.

Barring those kinds of major shifts to the Earth’s circulatory system, the brunt of the negative effects floods, severe storms and drought most likely will be felt by the world’s poor, clustered in the tropical and subtropical latitudes. Exacerbating the problem is that it is the developed world, much of it further north, that has distribution systems and the technology to adapt to changing climate.

“What makes this more complicated is the fact that most of the problem has arisen, and most of the solution must arise, in parts of the world that are not likely to be as severely impacted as parts of the world that did little to contribute to this problem and have little resources to address it,” McCarthy said.

‘A conservative view’

McCarthy’s colleagues at Harvard applaud the work of the IPCC for greatly increasing understanding among policymakers and the public about the scientific underpinnings of global warming.

But as alarming as one might think the IPCC’s findings are, they very well may be understating the danger, according to Daniel Schrag, professor of geochemistry and director of the Laboratory for Geochemical Oceanography.

Schrag said the IPCC is by nature a conservative organization. The breadth that gives its findings weight 3,000 scientists, reviewers, and government officials were involved in drafting the reports means that consensus had to be reached across broad points of view, including those from countries whose economies are based on oil production.

“This is inevitably a conservative view,” Schrag said. “This isn’t something coming from Greenpeace.”

Schrag points out that the IPCC’s projections are just that projections. Humankind is conducting a gigantic experiment to see what happens when you rapidly increase carbon dioxide to levels not seen for 40 million years. And no one knows the outcome, he said.

“This is an experiment that hasn’t been done on the Earth for a very long time,” Schrag said.

John Holdren, Heinz Professor of Environmental Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, credited the IPCC with largely ending the debate over whether human-induced climate change is happening.

Holdren said he believes that global warming which he prefers to term “global climate disruption” will come to be known as an even more difficult problem than people today expect.

“I believe that global climate disruption will come to be understood over the next few decades as the most dangerous and most intractable environmental problem faced by civilization,” Holdren said. “Up until now, it has been undersold more than oversold. Most people, even most scientists, do not understand the degree of dependence of human well-being on environmental conditions and processes that depend, in turn, on the climate.”

Contact Alvin Powell at alvin_powell@harvard.edu