A different direction

Exhibit of Latin American art holds surprises at every turn

What comes to mind when you hear the words “Latin American art”?

If you see images of peasants in yellow sombreros asleep against crumbling stone walls, bullfighters brandishing magenta muletas, or senoritas dancing in a swirl of purple skirts, then you owe it to yourself to visit a new exhibition at the Fogg Museum called “Geometric Abstraction in Latin American Art.”

“Many people assume that Latin American art must be colorful, figurative, representational, what I call ‘Chiquita Banana art,’” said Patricia Phelps de Cisneros in a recent phone interview. Cisneros is an art collector and philanthropist from Caracas, Venezuela, from whose collection the current exhibition has been selected. “One of our missions is to make audiences aware of another direction our art has taken,”

That direction has much in common with what was happening in the art worlds of Europe and the United States during the same period – from the early 1930s to the late 1980s. Paris provided a creative nexus for many of these Latin American artists, as it did for those from Europe and the United States. But it was assuredly not a case of Latin Americans scrambling to catch the bandwagon of the latest artistic trend. In many cases, their innovations paralleled or even preceded those of their European and North American counterparts.

“These works reflect the local character of these cultures, but they are fully engaged with modernism in Europe and America,” said James Cuno, the Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot Director of the Harvard University Art Museums.

For example, there are the Mondrian-like paintings of the Arte Concreto-Invencion movement in Argentina, which flourished in the mid-1940s. This group, which included Tomás Maldonado, Alfred Hlito, and Juan Melé, employed precise geometry, primary colors, a flat picture plane, and an emphasis on rational processes with no reference to nature.

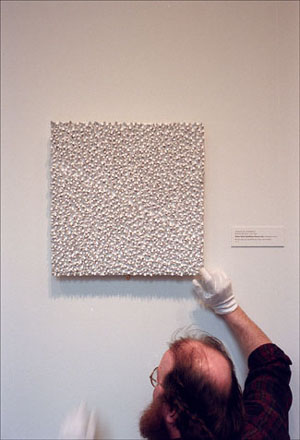

The Grupo Madi, which diverged from this movement, took a different approach, questioning basic assumptions about what a painting should be. “Trio 2” (1951) by Camelo Arden Quin of Uruguay also uses geometric patterns, but the unframed canvas itself is an irregular shape with no predetermined up or down. Its position on the wall is at the discretion of whomever is in charge of hanging it.

Meanwhile, in Venezuela, kineticism was the dominant artistic style. Promoted by the government, which sought to make the oil-rich country a mecca of modernism, kineticism aimed at conveying a sense of energy through the play of light over surfaces that combined qualities of painting and sculpture. In the “Physichromy” series by Carlos Cruz-Diez, for example, parallel colored strips that project out from the picture plane cause the appearance of the piece to change as the viewer shifts position.

Jesus Raphael Soto has improvised a number of variations on this theme, creating paintings that bristle with colored wires, paintings that suggest depth through the use of overlapping grids, and one arresting construction (Untitled, 1958) in which the viewer looks through a screen at a pattern of lines underneath. Any movement on the viewer’s part creates a tantalizing impression of flickering movement.

Gertrude Goldschmidt, known as Gego, a German-born artist who emigrated to Venezuela in 1939, was one of a group of artists who were influenced by the Swiss sculptor Max Bill. Her large, hanging wire sculpture “Sphere” (1976) is, in fact, not spherical at all, but roughly egg-shaped, and perhaps demonstrates her departure from Bill’s strictly geometric approach.

Another artist whose works demonstrate an evolution from hard-edged geometric abstraction to something more complex and organic is the Brazilian Lygia Clark. In her paintings of the 1950s, she moves from black-and-white abstractions which explore the relationship of figure to ground, to paintings that blur the line between canvas and frame, to compositions employing multiple picture planes.

These evolve further into sheet metal sculptures, some of which employ hinges, which allow the piece to be rearranged into a variety of different shapes.

The exhibition opened March 3 and will be on view through Oct. 21. The 60-plus paintings, drawings, and sculptures in the exhibition are only a small part of Patricia Phelps de Cisneros’ collection, which maintains an active worldwide lending program.

Cisneros said that her collecting began when she bought a small print as a student at Wheaton College. She continued to acquire art “out of the need that the soul has to be surrounded by beauty.” It was not until a prominent American art journal called her about 20 years ago to inquire about her collection that she began to think of her artworks in that context.

“As soon as I began thinking of it as a collection, I had to become more responsible. It was still a joy, but I had to start thinking about hiring curators, cataloging, conservation, and showing it to the world, which is a mandate, I think.”

Cisneros, along with her husband, Gustavo, the head of the Cisneros Companies, a media conglomerate, and her brother-in-law Ricardo, are founders of the Fundación Cisneros, a private philanthropic organization dedicated to improving the quality of life in Latin America and increasing global awareness of Latin American culture.

Cisneros said she was particularly grateful to the University Art Museums and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, co-sponsors of the exhibition, and to Neil L. and Angelica Zander Rudenstine, whose support helped the exhibition come about.

For more information, call (617) 495-9400, or visit http://www.artmuseums.harvard.edu.