Memories of Pain Can Come Back To Hurt

Newly found connections between pain and memory are leading to novel ways to control pain.

Nerves carry pain signals to the spinal cord and brain where they excite cells involved with making memories of pain, according to Clifford Woolf, Kitz Professor of Anesthesia Research at Harvard Medical School. This excitation is a main contributor to post-injury pain. It produces an increased sensitivity that can last for months.

“As we search for the molecular basis of pain, we keep uncovering associations between pain and memory,” Woolf says. “Blocking such associations can provide a new basis for treating pain.”

As an example, to decrease excitability, patients were given spinal injections of painkillers before prostate surgery. Compared with those not so treated, they experienced less pain while hospitalized and were more active after surgery. The pain reduction lasted as long as nine and a half weeks.

“When you think about it, the link makes sense,” Woolf points out. “During evolution, animals had to learn to recognize what causes pain and to remember to avoid such things. A one-celled amoeba moves away from too much heat just as a human avoids a hot stove.”

ERKs Signal Hurts

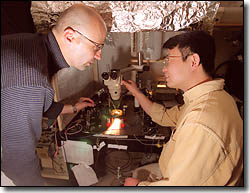

Woolf came to Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston two years ago to research the origins of pain and to apply the results to treating patients. While working in London in 1983, he discovered that pain alters the nervous system in a way that makes parts of it sensitive to pain for hours to months. That memory, he concluded, is responsible for the pain we experience after surgery, a tooth removal, or any wound that makes an area sore to the touch for some time.

But how is this memory made? A few years ago, researchers found molecules they call ERKs extracellular signal-related kinases. These proteins carry signals from the surface of cells to the genes in their nuclei, changing how the cells function by changing the way genes are turned on or off. In others words, an ERK can change the memory of cells in the spinal cord and brain.

In the past few months, Woolf and colleague Ru-Rong Ji put the two findings together to show how ERKs provide a link between pain and memory. If you have abdominal surgery, you dont feel any pain because you are under anesthesia. However, the cutting of skin and muscle produces a barrage of distress signals that travel, via nerves, to ERKs in nerve cells of the spinal cord. The ERKs, in turn, cause short- and long-term changes to nerve cells in the spinal cord and the brain area where the sensation of pain is “felt.”

When you awake from anesthesia, these altered cells retain their excitability, or sensitization, prolonging your pain and soreness. “The post-operative pain is a manifestation of switching on the memory of the pain that occurred during the surgery,” Woolf says.

Giving Drugs Before Pain

That conclusion opens the way for novel ways to treat pain. One obvious way is to give painkillers before patients feel pain, not after, a procedure doctors call “preemptive analgesia.”

In the prostate study mentioned above, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine injected painkillers into the spines of 66 patients before surgery to remove the prostate gland. These patients then compared their pain experiences with those of 30 other men who got general anesthesia only. Allan Gottschalk and his research team reported that the “preemptive analgesia significantly decreases postoperative pain during hospitalization and long after discharge, and is associated with increased [physical] activity levels after discharge” from the hospital.

The powerful drug morphine is now being used this way. “By administering it before, rather than after treatment, we have shown in patients undergoing hysterectomies that much smaller doses can be given,” Woolf points out. “Such acute use of the drug produces no addiction.”

However, morphine has unpleasant side effects, including nausea, sedation, depression, and the potential for abuse. “Its an effective but not an ideal drug,” Woolf comments. “What we want is a drug with the same efficacy but much fewer side effects. We think one answer lies in finding substances that block the action of specific ERKs in the spinal cord.”

Woolf and his colleagues reported in the December issue of Nature Neuroscience that they used this technique to block pain in rats. The animals received injections of capsaicin, the active ingredient of chili peppers that produces an intense burning sensation. Capsaicin is sometimes given this way to humans who volunteer for tests of new painkillers.

Drugs used to block ERKs in rats wont do the job in humans, so Woolf is collaborating with several pharmaceutical companies to develop more selective drugs. ERKs act on practically all cells in the body, and the aim is to find inhibitors that specifically target ERKs in the human spinal cord.

At the same time, the researchers pursue such basic questions as precisely how ERKs produce pain. “We believe we have found the receptor on spinal-cord cells that these proteins act upon,” Woolf notes. “Called NMDA, its a key to controlling the excitability of nerve cells.”

The next step involves learning how ERKs change NMDA to produce the sensation of pain and form a memory of it.

Finally, theres the question of which genes are switched on in nerve cells to produce pain and its memory. “Were becoming gene hunters,” Woolf comments, “hunting for genes that cause both good and bad pain.”

The researchers dont want to turn off the kind of pain that warns you to avoid something thats too hot, sharp, or chemically noxious. People who cant feel this kind of pain may suffer severe mutilation and reduced life spans. The goal is to avoid the increased excitability that produces the hurt of arthritis, postoperative surgery, broken bones, and other wounds and diseases.

“When ether was first introduced in 1846 at Massachusetts General Hospital, it was hailed as an anesthetic that would eliminate pain,” Woolf notes. “After 150 years, this has yet to be achieved; theres still a tremendous unmet need for relieving pain. But by understanding the mechanisms involved at the level of cells and molecules, eliminating pain is becoming a more realistic prospect.”