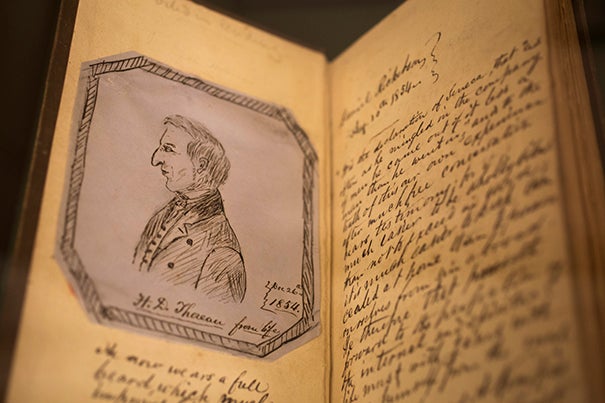

A Houghton Library exhibit contains ephemera related to poet and scholar Henry David Thoreau, such as this annotated 1854 copy of “Walden, or Life in the Woods,” owned by a friend of Thoreau.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The Harvard in Thoreau

As the bicentennial of his birth nears, it’s clear the College influenced him more than he’d have admitted

More like this

Like countless students before and since, Henry David Thoreau, Class of 1837, had his problems with Harvard. It was too fixed on drilling and grades for him, his classmates were too rowdy, and on the whole he would rather have been in the woods of Concord. Indeed, he was in those woods, he wrote in his class book, for “hours that should have been devoted to study.”

In 1840, he dismissed the unearned master’s degree that Harvard offered him, as it did then to all alumni three years after graduation. “Let every sheep keep its skin,” he sniffed. And when Ralph Waldo Emerson said that Harvard taught all the branches of knowledge, Thoreau replied: “Yes, all the branches and none of the roots.”

Now, however, as we celebrate the bicentennial of his birth, on July 12, 1817, it is clear that his protest should not be taken too seriously. Harvard profoundly influenced Thoreau and helped make him who he was, whether he said so or not.

As a student, he devoured its books, reading many of them outside of classes. The library was also indispensable to his later literary career and work as a naturalist. Thoreau told Emerson’s son Edward that Harvard’s library was the “the best gift” the College had to offer. At Harvard he also began his habit of copying passages that struck him, filling 20 “commonplace” notebooks with a million words.

Thoreau was introduced to Transcendentalism when he read Emerson’s new manifesto, “Nature,” in his senior year, became acquainted with “Hindoo” and other Eastern writings, and developed his interest in poetry and in European languages while at Harvard. By the time he left, he could read Greek, Latin, Italian, German, and French.

Thoreau studied the ancient Greek and Roman writers intensely, an immersion that formed his belief that the world of which the poets Homer and Virgil sang is no different from the world today. His love of the classics would also suffuse his writing: While it was often about plants and ponds, Homer, Cicero, and Pliny were never far behind.

David Henry Thoreau, as he was then known, entered Harvard on Aug. 30, 1833, at age 16. The College had fewer than 20 professors or instructors, cost $179 a year, and can scarce be imagined physically on today’s megalopolis campus. It consisted of six brick buildings clustered on the west side of the Yard, across from First Parish Church. All classes were held in Massachusetts Hall. There were three dormitories (Hollis, Holworthy, and Stoughton), the chapel, and Harvard Hall, which held 50,000 books.

Students were given cannonballs to heat and use as bed warmers during cold weather. They lost points, and thus scholarship money, in President Josiah Quincy’s elaborate ranking system if they rolled them down the stairs, which they did anyway, or failed to appear in the unheated chapel for prayer at 6 a.m. (In a liberalizing gesture, this was moved to a half-hour before sunrise in winter.) Dining was not today’s varied affair: only coffee or tea and rolls, which Thoreau said tasted like wool, morning and evening, with a midday dinner of meat.

A fellow student’s poison-pen description of Thoreau walking with downcast eyes and a disdainful expression created the perception that he was morose and aloof at Harvard, but later findings have cast doubt on this. The Thoreau scholar Raymond Adams, writing about the spirited letters Thoreau exchanged with classmates who became close friends, said he “took pleasure in college life” and was not as unhappy as people thought.

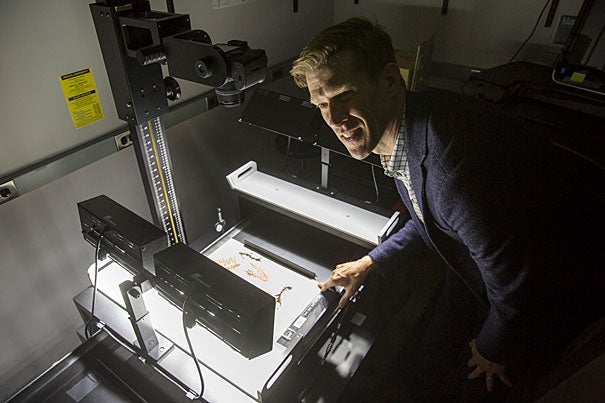

Ronald A. Bosco, the editor of numerous scholarly works related to Transcendentalism and guest curator of a new Thoreau exhibit at Harvard’s Houghton Library, agrees. “Thoreau made lasting friends at Harvard and enjoyed much of the learning process,” if not its regimented style. He also “remained connected to the College through its library” after leaving Harvard. Thoreau successfully petitioned for borrowing privileges in 1849.

Thoreau’s reserve may have contributed to the misperception. While he wrote in his class book that his fellow students had a place “in my heart,” he said it was “too sacred a matter” to speak of directly. Instead, he quoted the Scottish poet Robert Burns on the pain of being severed from friends.

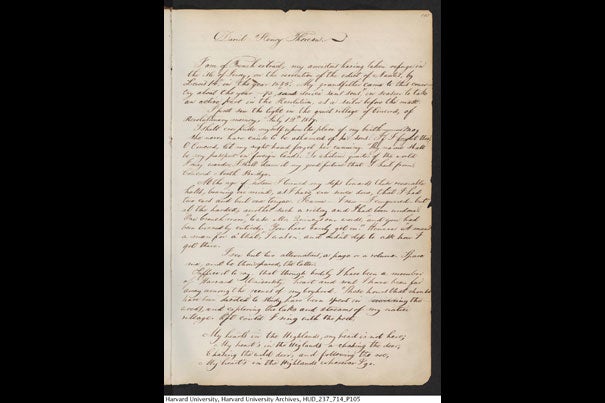

But it is true that in many ways Harvard and Thoreau were ill-suited. He didn’t want to go, and he never liked being away from rural Concord. “Though bodily I have been a member of Harvard University, heart and soul I have been far away among the scenes of my boyhood,” he wrote in his class book, “scouring the woods, and exploring the lakes and streams of my native village.”

The cost of Harvard was hard on his family, which caused him to take a leave to teach school in his third year. No sooner was he back than he had to withdraw again, this time for illness, a preliminary bout with tuberculosis.

But Thoreau’s main beef with Harvard was its emphasis on drilling and rote memory, rather than what he identified as true teaching. He said the College fostered “superficial scholarship” instead of critical thought. Quincy’s arcane, and hated, marking system, which rated students on daily recitations, chapel attendance, and general behavior as well as compositions and tests, especially irked him. Thoreau was one of 34 members of his class who asked Quincy in 1834 to abolish it.

The faculty was small, but it was distinguished. Thoreau had high regard for Edward Channing, professor of rhetoric. Thoreau said he learned to express himself during three years of English with Channing — a rare compliment from him to the College. Thoreau was also impressed by Henry Ware, a liberal Unitarian whose appointment as professor of theology in 1805 caused a fracture with Harvard’s orthodox Puritans. One of the very rare times that Thoreau attended the First Parish Church in Concord as an adult was when Ware preached there in 1840. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who joined the faculty when Thoreau was a senior, deepened his interest in German literature and poetry.

He gained an introduction to natural history his senior year when he studied with Thaddeus William Harris, the College librarian and an early entomologist. Harris called him an enthusiastic student of insects but said it was unfortunate that he had just read “Nature.” Thoreau would have made a fine entomologist, Harris said, “if he hadn’t been ruined by Emerson.”

Cornelius Conway Felton, with whom Thoreau took three years of Greek grammar, composition, and literature, deepened his love of the classics. Felton was distinguished as a teacher of Greek, but he did not distinguish himself as a judge of character in his estimate of Thoreau. He was “a scholar of talent,” Felton said, “but of such pertinacious oddity in literary matters, that his writings will probably never do him any justice.”

Bosco observed that for all its positive influences, Harvard was not where Thoreau was primarily educated. Noting that “Melville admitted that the sea was his college,” he said, “Thoreau truly began his serious intellectual development as a student of Concord and nature.”

In later life, Thoreau never let up on Harvard. In 1854, he mocked claims the College made about the practical application of spherical geometry, which he had studied. “To my astonishment I was informed on leaving college I had studied navigation!” he wrote. “Why, if I had taken one turn down the harbor I should have known more about it.” Instead of helping Harvard, he said, men should consider giving money to their towns to preserve and protect a huckleberry patch.

But Thoreau’s intellectual growth at Harvard was evident at his graduation, at which he was entitled to speak by his grades. In his oration, he sounded some of the themes he would embed in his classic book “Walden” around 15 years later. The “commercial spirit” of the day, he said, rested on a love of wealth that made people selfish and greedy. The world would be a better place, he said, if people “made riches the means and not the end of existence.”

“The sea will not stagnate, the earth will be as green as ever, and the air as pure,” he said in the Yard on Aug. 30, 1837, long before the planet’s pollution became a fixture in graduation speeches. “This curious world which we inhabit is more wonderful than it is convenient; more beautiful than it is useful; it is more to be admired and enjoyed than used.”

Thoreau also ventured that people erred by working six days and resting one — a thought he would develop at length in the “Economy” chapter of “Walden.” “The seventh should be man’s day of toil, wherein to earn his living by the sweat of his brow, and the other six his Sabbath of the affections and the soul — in which to range this widespread garden, and drink in the soft influences and sublime revelations of Nature.”

His classmates’ bacchanal parties roared into the night, but without Thoreau. After receiving his diploma, he returned home to Concord and to his natural studies.

Richard Higgins is author of the new book “Thoreau and the Language of Trees,” published by the University of California Press. He lives in Concord, Mass.