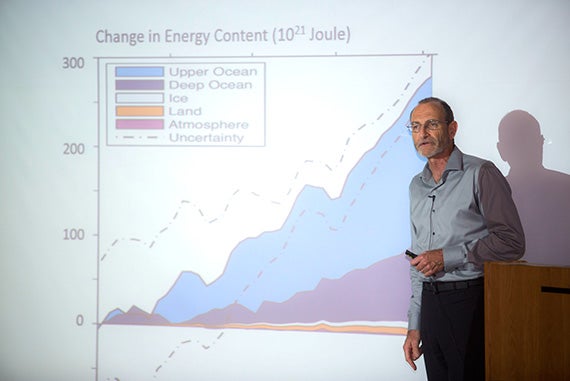

At Harvard’s 10th annual Plant Biology Symposium, climate expert Chris Field ’75 talked about the need to evaluate environmental risks in the coming decades even as many people work to reduce climate-warming emissions.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The era of climate responsibility

Expert says upcoming decades will require assessing risk, overseeing mitigation, managing adaptation

With climate change a settled a fact among the great majority of scientists, people are entering an era of “climate responsibility,” during which the actions they take — or fail to take — will lead to a dramatically different world for future generations, a leading climate expert said Tuesday.

Chris Field ’75, co-chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Working Group II and founding director of the Carnegie Institution for Science’s Department of Global Ecology, said the coming decades will provide an opportunity to curb emissions drastically and to begin efforts to counter risks from changes already “baked into the system” by past emissions.

“We can think of the next few decades as an era of climate responsibility,” Field said. “During this period, the actual evolution of temperature is very different between a world of continued high emissions and a world of ambitious mitigation.”

Over the past century, Field said, the globe has warmed about 1 degree Celsius, and even the most optimistic emissions scenarios have it warming by that much again by 2100.

That means a wide array of effects are already unavoidable, he said, ranging from more-extreme weather events, to longer and more severe heat waves and droughts, to shifting environments for many plant and animal species, to strain on the global food supply, to disappearing global ice, rising seas, vulnerability to insect-borne disease, and more.

Keeping climate change to that level, however, will require dramatic changes to global carbon emissions. From 1970 to 2000 these rose at about 1.3 percent annually, but from 2000 to 2010 they rose 2.2 percent a year, meaning that carbon emissions are increasing, not decreasing.

If those increases are not curbed, Field said, the globe could warm as much as 5 degrees Celsius by 2100, with effects that will be much greater and more difficult to counter.

“The risk of future impact goes up dramatically as the amount of climate change goes up, with increasing risk of impacts that are severe, pervasive, and irreversible,” he said.

Field, who also serves on Harvard’s Board of Overseers, was the opening speaker Tuesday at the Geological Lecture Hall for the two-day, 10th annual Plant Biology Symposium. The gathering was cosponsored by the Plant Biology Initiative at Harvard University and by the Harvard University Center for the Environment. Field was introduced by Andrew Richardson, associate professor of organismic and evolutionary biology.

Though much work remains to be done, Field said there are hopeful signs that needed shifts are occurring. He cited as examples the recent announcement by California Gov. Jerry Brown that the state would further tighten greenhouse-gas emissions standards and the U.S.-China agreement last November on curbing carbon emissions.

The changes may not be good news for the fossil fuel industry, Field said, but could mean economic opportunities for many other sectors. Billions of dollars will have to be spent to renew aging infrastructure across the globe in the coming decades, and with the renewal will come opportunities to incorporate sustainable innovations in design. In addition, he said, there are already signs that governments and their people are taking existing threats seriously and making early steps to mitigate effects and adapt.

In the Netherlands, he said, new flood control infrastructure is an example of a top-down governmental approach against rising seas. Meanwhile, on the island of Tuvalu in the South Pacific, communities are seeking to buffer the impact of rising seas and storms by planting mangrove forests.

These efforts “are unique in that they’re specifically deployed to provide protection from a changing climate, and they’re intended not as final solutions but as initial efforts to provide … learning experiences to build on moving forward,” Field said. “They all represent baby steps from which we can learn.”

The extent of the mitigation and adaptation efforts undertaken, he said, will depend in part on the risks from climate-driven events and the degree to which people, businesses, and governments determine their risk tolerance based on their vulnerability to impact, its potential for damage, and its likelihood.

Asked whether he had any advice for today’s college students, Field said the challenges are many and he can’t imagine a field where the efforts of talented individuals won’t be needed.

“What I hope is one of you guys are going to be the CEO of ExxonMobil, and that’s what’s really going to make the difference, or … governor of Massachusetts, or president,” Field said. “I actually can’t think of any future endeavors that are not involved with climate … The opportunities for contributing solutions to the climate problem are everywhere.”