Ghosts in the machines

The history of the Digital Revolution touches our hearts and heads, Isaacson says

In many ways, the entire Digital Era can rightly be laid at the courtly foot of Lord Byron’s rebellious daughter, Ada. Lady Lovelace was the poet’s only child born in wedlock, inheriting both her father’s headstrong, Romantic spirit and her mother’s practical respect for mathematics.

As the Industrial Revolution bloomed, her appreciation for the beauty of numbers and invention, an analytical approach she called “poetical science,” led her to write what is now regarded as the first algorithm and to help refine a machine that could be programmed to perform many different tasks, an idea that anticipated the modern computer by a century.

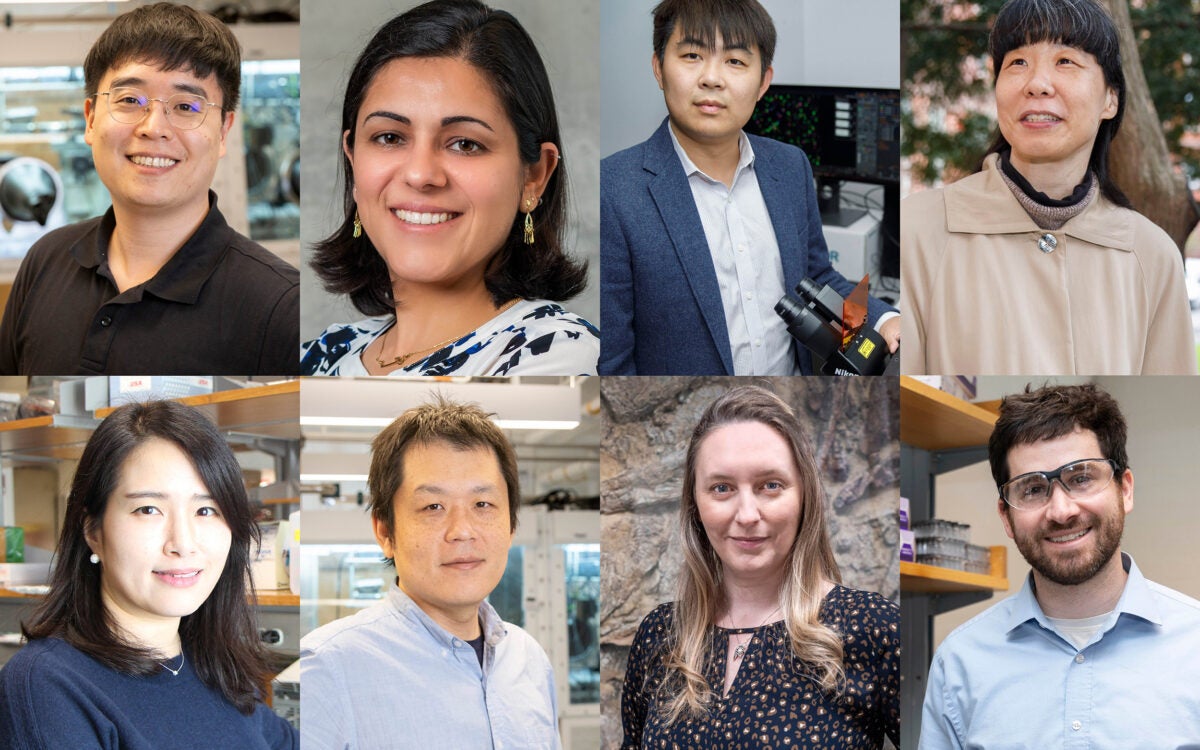

That’s where Walter Isaacson’s latest book, “The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution,” steps off. Nominated for a National Book Award, Isaacson takes a sweeping look at the history of the computer and the Internet as seen through the many creative characters who contributed both breakthrough and incremental advances to our technological evolution. It’s a richly told tale of towering figures like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, but also of unsung innovators, including a team of women at the University of Pennsylvania who secretly programmed the ENIAC computer during World War II.

Isaacson ’74 is the best-selling author of landmark biographies of Jobs, Albert Einstein, and Benjamin Franklin. A former journalist who has headed CNN and Time magazine, Isaacson is currently CEO of the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies think tank in Washington, D.C., as well as a Harvard Overseer. He spoke with the Gazette about what he learned in his research and how truly lasting innovation is often found where our humanity meets our machinery.

GAZETTE: What drew you to a subject as complicated and fluid as the history of the Digital Revolution?

ISAACSON: I was always an electronics geek as a kid. I made ham radios and soldered circuits in the basement. My father and uncles were all electrical engineers. When I was head of digital media for Time Inc. in the early 1990s, as the Web was just being invented, I became interested in how the Internet came to be. When I interviewed Bill Gates, he convinced me that I should do a book not just about the Internet, but its connection to the rise of the personal computer. So I’ve been working on this for about 15 years. I put it aside when Steve Jobs asked me to do his biography, but that convinced me even more there was a need for a history of the Digital Age that explained how Steve Jobs became Steve Jobs.

GAZETTE: You’re known for your “Great Man”-style biographies, and yet this is a story about famous, seminal figures and the lesser-knowns who contributed to the Digital Revolution in some way. Can you tell me about that approach?

ISAACSON: The first book I did after college (with a friend) was about six not very famous individuals who worked as a team creating American foreign policy. It was called “The Wise Men.” Ever since then, I’ve done biographies. Those of us who write biographies know that to some extent we distort history. We make it seem like somebody in a garage or in a garret has a “light-bulb moment” and the world changes, when in fact creativity is a collaborative endeavor and a team sport. I wanted to get back to doing a book like “The Wise Men” to show how cultural forces and collaborative teams helped create the Internet and the computer. There’s no one person you can put up there with Thomas Edison and say, “He or she invented the Internet or the computer.” My biography of Henry Kissinger begins with a quote of his in which he said, while flying on one of his shuttle missions to the Middle East in the 1970s, “As a professor, I tended to think of history as run by impersonal forces. But when you see it in practice, you see the difference personalities make.” I wanted to look at the interplay between the cultural forces, including wartime government funding as well as the explosion of digital concepts, and to what extent that related to the creativity of individual players.

GAZETTE: At a time when the technology sector faces criticism for its lack of gender and racial diversity, you focus on a number of women who played very significant roles in the evolution of technology. Were you surprised at how central women were?

ISAACSON: I think women have been unfairly minimized in the history of technology. Even at Harvard, the great programming work done by Grace Hopper on the Mark I computer that’s in the lobby of the Science Center was instrumental in distinguishing that machine from others at the time that were not reprogrammable. And yet until recently, the panels in front of that machine had no pictures of women, just all of the men who had built it. Even the manual sitting in front of the machine that you can flip through was written by Grace Hopper. Her name’s not on it — it says “by the team” — but she’s the one who wrote it. Now, that display has been revised with pictures of Grace Hopper and some of the other women. I think it’s important to realize that, especially in the area of open-source programming, women including Grace Hopper and the women who programmed the ENIAC at Penn are in the tradition of Ada Lovelace, women who conceived of the power of software programming.

GAZETTE: So many people who were instrumental to this history were unconventional and, in some cases, misfits of their era, either by intellect, interest, or temperament. Is it an accident that outsiders drove the evolution of digital technology, and did that outsider status shape the way tech favors openness and less-bureaucratic institutions?

ISAACSON: Yes, I think there’s a glorious geekiness that comes with a lot of the great innovators in the tech revolution. Their imprint is in the DNA of how the Internet and personal computers were developed. In particular, the fact that a whole group of slightly rebellious, anti-authoritarian graduate students created the protocols for connecting host computers to the original ARPANET helped to create the decentralized and distributed nature of that packet-switch network.

GAZETTE: Harvard probably doesn’t first come to mind for most people when thinking about the history of computers and the Digital Revolution. Can you talk about role the University played?

ISAACSON: The first programmable electromechanical computer is the Mark I, developed at the Harvard Computation Lab and now in the lobby of the Science Center. The notion that it could be easily reprogrammed was pioneered by Lt. Grace Hopper and an ensign named Richard Bloch, who worked on programming that computer. Also, the combination of Harvard and MIT created companies like BBN Technologies in Cambridge that built the original routers for the Internet. I also think Harvard has remained a cradle for connecting bright, creative people to technology, from Bill Gates to Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg.

GAZETTE: One of the book’s foundational themes is the intersection of science and the humanities and how understanding and valuing both has brought us some of the most important innovations. Why is that, and are we in an era right now where the pendulum has swung too far in the direction of valuing S.T.E.M. education and not enough on liberal arts?

ISAACSON: Whenever Steve Jobs had a product to launch, he’d end with a slide showing a street-sign intersection of the liberal arts with technology. And he said, “That’s where the value is — when we can connect our humanity with our machines.” The great theme of the Digital Age is not creating new machines that can think alone, but machines that work in partnership with humans. That ability to connect “that which makes us humans” with machines begins with the interactive graphical displays created for the original air defense systems and goes to Xerox PARC, to Apple Computer, and many other great and beautiful technological innovations. Steve Jobs loved taking calligraphy and dance and art, and the reason he loved a bit-mapped user interface was because he could create beautiful fonts for the original Macintosh. And he had a simple rule, which is that “beauty matters.” It helps make us intimate with our technology.

I think the first phase of the Digital Revolution — the past 50 years — was to some extent engineering-driven. We’re now in a phase in which the connection of creativity to technology is going to drive innovation. I do believe that it’s important for people to have an appreciation for the arts and humanities. But I also think that one problem is people who love the arts and humanities are too often intimidated by science and math, and they don’t appreciate the beauty of science and math. They’d be appalled if somebody didn’t know the difference between Hamlet and Macbeth, but they could happily brag that they don’t know the difference between a gene and a chromosome, or an integral and differential equation, or a transistor and a capacitor. So as much as I’d like to lecture the engineers that they should appreciate the humanities, I also think that people from the tradition of the humanities should embrace the beauty of engineering and science, as well.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.