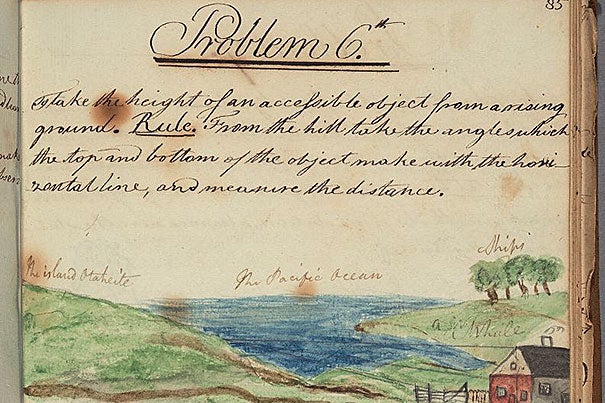

Among the 33,000 Colonial North American images Harvard has digitized so far is “Problem 6th” from the 1795 student mathematical notebook of William Tudor (1779-1830), who graduated from Harvard College in 1796. He used the drawing to playfully transport himself to an island in the Pacific Ocean. Tudor became a leading literary figure in Boston, coined the phrase “Athens of America” for his native city, and helped found the first American railroad.

Images courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

A Colonial goldmine

Two digital projects aim to bring vast numbers of early documents, many unexamined, to light

Historians and archivists know a secret that most of us do not: that vast stores of primary documents about North America’s Colonial era lie untouched and unseen in repositories throughout the United States and Canada.

The papers of the Founding Fathers and other prominent figures are well known, said University Librarian Robert Darnton, who is Harvard’s Carl H. Pforzheimer University Professor and a historian of early modern France. But much archived material — a lot of it related to the economic and social life of the Colonies — has not been fully examined.

With Darnton in the lead, Harvard is doing something about that by digitizing documents for its Colonial North America (CNA) project. “There are fabulous holdings in unexpected places,” he said.

Having 73 libraries gives Harvard the advantage of volume. Taken as a whole, the University’s archival and manuscript repositories house more than 45,000 collections, according to a 2010 survey, which include nearly 190,000 linear feet of boxes. (One linear foot is equivalent to about 2,000 items or pages.) Harvard’s collections contain approximately 400 million items, from single pages to folders. There are 35 miles of manuscripts at Harvard, said Darnton in one report, “much of it unprocessed.”

Of the material surveyed, about 6,900 linear feet — around 30 million pages — date from the 17th and 18th centuries. This includes 1,654 relevant collections at 12 Harvard repositories, according to Ceilyn M. Boyd, a Harvard Library senior project manager. Chief among the Harvard sites for these Colonial archives — about 60 percent of which are in English — are the Harvard University Archives, Houghton Library, and the law, business, medicine, and divinity Schools.

“This is one of the few places in the country where this kind of material has built up over the ages,” said Darnton. “Much has not been seen by historians. As an historian myself, I’m astonished.”

Leafing through journals

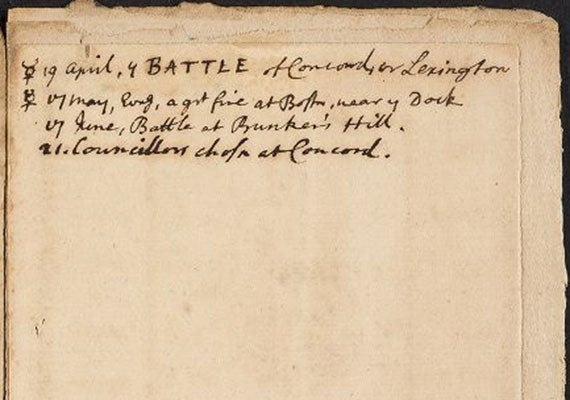

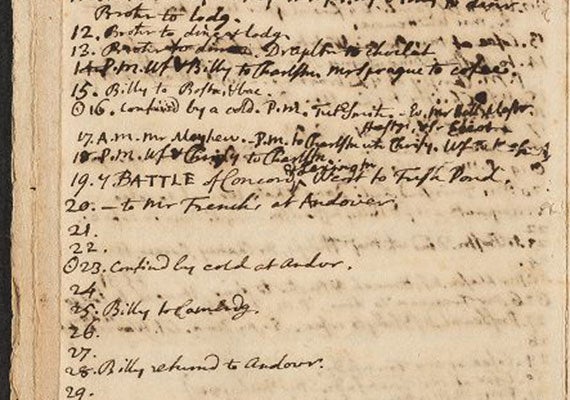

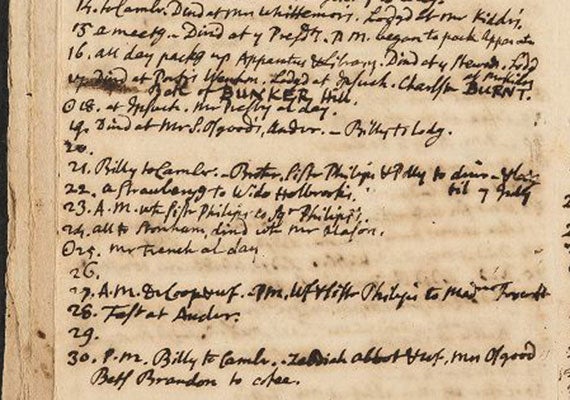

One leaf from a 1775 journal kept by Harvard scientist and professor John Winthrop (1714-1779) in that year’s Bickerstaff’s Boston Almanac. The list notes the battles of Lexington and Concord (April 19) and Bunker Hill (June 17) and Harvard’s one-year refuge at Concord (June 21).

The Winthrop entries for April 1775 juxtapose the prosaic and the historic. “BATTLE of Concord & Lexington,” he notes on the 19th, adding: “Went to Fresh Pond.”

On June 16, 1775, Winthrop “all day packg up Apparatus and Library” for the move to Concord. On June 17, after noting his dining and lodging arrangements, he records “Charlestown BURNT. Batt of BUNKER Hill.”

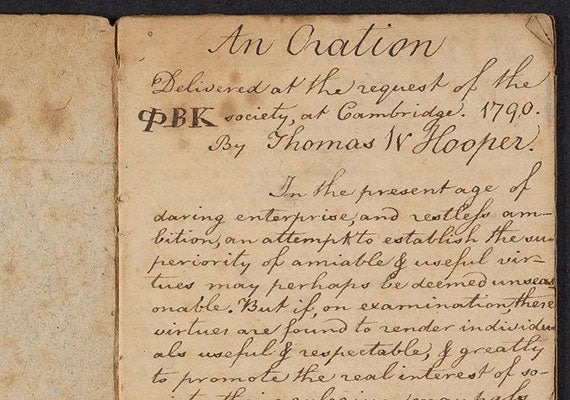

The 1790 Phi Beta Kappa Oration by Thomas W. Hooper (1771-1816), who defined the post-Revolutionary American age as one of “daring, enterprise and restless ambition.”

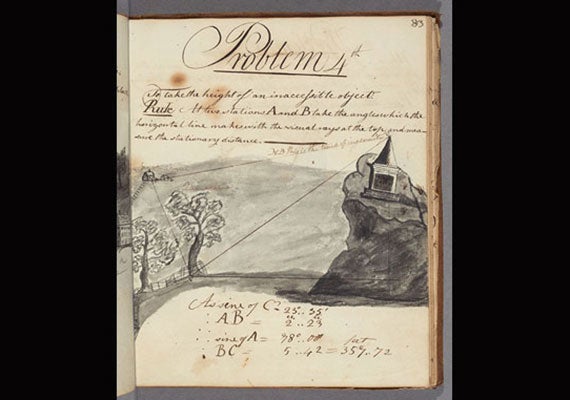

In “Problem 4th” of his 1795 student mathematical notebook, William Tudor adds some undergraduate wit: a spire perched on a high rock speckled with weeds.

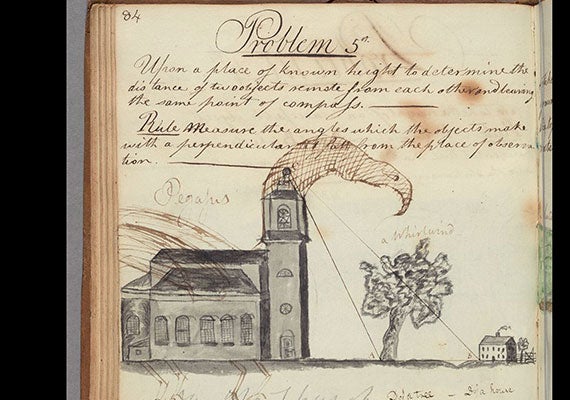

Later doodles on William Tudor’s “Problem 5th” transform a Cambridge church into a giant Pegasus, complete with legs and sweeping wings. But the divine horse of Greek mythology is given the head and beak of a raptor, peering hungrily at what might be Massachusetts Hall.

By December, the CNA project, which is supported by the Arcadia Fund, expects to conserve and digitize at least 109 of the relevant collections, said Boyd, who added that a Nov. 1 progress report said about 33,000 images have been digitized so far from three Harvard repositories.

Great age and a certain historical centrality are also factors in how large the University’s Colonial holdings are. “This is where education began in what is the United States,” said Darnton. “And to a considerable extent, this is where the United States began.”

But the Harvard collections are only part of what is a vast array of similar archival material in repositories throughout the continent, most awaiting digitization. So another project is in the planning stages. The Colonial Archives of North America project (CANA) will draw on collections at Harvard and at partner historical societies, archives, and libraries. Among them are the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Boston Public Library, the New York Public Library, and Montreal’s Bibliotheques et Archives nationales du Quebec, which already has digitized much of its holdings.

The project is an ambitious collective enterprise. “We will create a gigantic database that will give us digital access to the entirety of [[archives]] in the Colonial world,” said Darnton, “on a scale that has not before existed.”

The database, Harvard experts pointed out, will be in the form of shared metadata linked to digitized collections at the partner institutions that own the actual documents. This “data about data” — a sort of 21st century card catalog — makes items easier to find by person, date, period, or some other contextual clue.

The project will reunite collections that were scattered starting hundreds of years ago. Darnton joked about the apparent opportunity Harvard had in 1787 to be the sole repository for the papers of Boston-area Founding Fathers. “Think of it,” he said.

Since then, some of those papers have returned to Harvard in “haphazard ways,” said Darnton, while others remain in archives in Boston, New York, Montreal, and elsewhere.

University archivist Megan Sniffin-Marinoff remembered that 1787 moment too. “The library was still developing” then, she said, and not in the business of actively collecting many of these archival documents, giving historical and genealogical societies of the 18th century — many of them with Harvard associations — “a jump on Harvard.” (It was only in 1851 that Harvard began systematically documenting even its own history.)

Now comes the digital age, said Darnton, and with it the possibility that scattered papers and archives can be reunited virtually. With them will come a flood of documents that have lingered in the scholarly shadows, but that have the potential for illuminating the age that gave North America much of its present social and geographic character. Among those documents are many records on businesses, poverty, public health, and relief to the indigent.

Darnton is taken with the idea that such archives might also illuminate the lives of Colonial women and working classes, since he is a believer in the idea of “history from the bottom up.” But Darnton also admits the difficulty historians face in understanding the common man. In a 1984 essay called “The Meaning of Mother Goose,” he even advocated a new look at fairy tales as a means of uncovering the lost daily realities of the past.

Darnton is a staunch defender of traditional print (publishing “The Case for Books” in 2009). But he is also a champion of digital’s potential for scholars, classrooms, and readers. (Darnton is one of the moving forces behind the Digital Public Library of America, which went live in April and recently held a Boston conference.)

The digital age can help to recover lost worlds, said Darnton, going well beyond the stories of great men and big events. He pointed to the recent discovery at Harvard’s Houghton Library of manuscript petitions from 1767 Boston, signed pledges to boycott British goods. The signatures of men and women are freely mixed, and provide a stunning new portrait of the city’s patriot class. “I was amazed,” said Darnton. “There were many signatures of women.”

Such discoveries will be accelerated for Colonial-era researchers by the volume, the serendipity, and the interconnectivity of the archive’s metadata. “There is enough in this for graduate students to write Ph.D.s indefinitely,” he said.

As an example, Sniffin-Marinoff discussed the 18th-century papers of John and Hannah Winthrop at Harvard. Assembled, they provide a rich portrait of the first prominent scientist to teach at Harvard. John Winthrop was one of the foremost scientists of his time. But the documents also reveal the inner workings of the Winthrop household.

In a June 16, 1775, diary entry scrawled in an almanac, Winthrop recounts spending the day packing up Harvard’s library and scientific instruments for the move to Concord ahead of British troops. (For safety, the students spent 1775-1776 there.) On the 17th, he noted in bold letters, was the Battle of Bunker Hill.

On other days, the journal records meeting for coffee (pointedly, not British tea) with John Adams, John Hancock, and other revolution luminaries. The Winthrop papers, digitized as part of the archive project, “make more accessible the perspective of a Harvard professor being deeply engaged in the affairs of the country,” Sniffin-Marinoff said.

The digitizing also holds the promise of providing access to a more detailed picture of Native Americans, she said. “Some of those details are hidden in plain sight within Harvard’s administrative records.”

Sniffin-Marinoff and Darnton pointed to other discoveries already digitized, including whimsical and revealing Harvard student notebooks from the 18th century. (Both have examples hanging in their offices.) The notebooks with illustrated mathematical problems sometimes provided an excuse for students to draw Harvard as it was, or an opportunity for teenage doodling.

“We are getting on with it no matter what,” said Darnton of Harvard’s own digitization project. The larger project is moving along too. It already has a technology committee and is putting in place structures for content and administration.

The larger, bi-national archive project — with its partners at public archives, public libraries, and historical societies — “takes what we are doing at Harvard and moves it out into the world,” said Sniffin-Marinoff.

The next step is for the partners to finish writing a joint application for a grant.

Darnton is optimistic that funding will come for an international archives project that is at once so vast and so vital, providing an opportunity to dive deep into the Colonial realities that made North America. “I can’t imagine,” he said, “being turned down.”