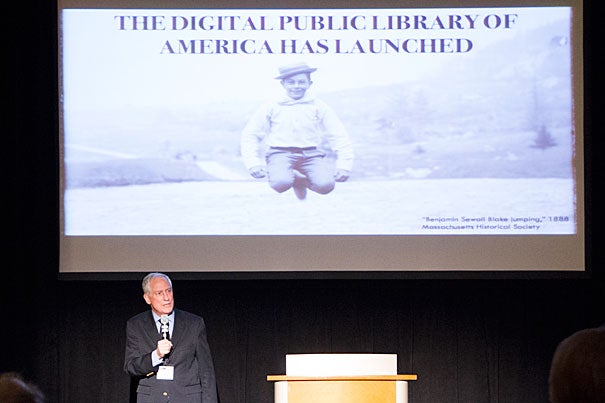

Robert Darnton, Carl H. Pforzheimer University Professor and University Librarian, spoke at the opening reception of the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) at the Boston Public Library last week (photo 1). David Weinberger of the Harvard Library Innovation Lab (photo 2) explained StackLife, a digital browsing tool developed at Harvard that allows a user to see at a glance the popularity of a given book, to Amanda Page, a library assistant at Countway Library.

Photos by Michelle Jay

National digital library gains traction

Conference celebrates strong early growth, plans for wide-ranging future

For a 6-month-old, the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) already has grown quite large: from an initial 2.4 million available items in April to more than 5 million.

Fame came fast too, “even in our infancy,” said DPLA Executive Director Dan Cohen. This free online portal into American culture was less than three weeks old when Time magazine named it one of the best 50 websites of the year.

DPLA is an enormous free public library under a digital roof. With a few clicks of computer keys, users can access millions of links to online books, photographs, movies, and other cultural artifacts from collaborating institutions, including digital collections at the Harvard Library.

Member libraries, museums, and exhibits contribute links for digitized materials — “metadata” — to nine regional or state aggregators, called service hubs. Twelve such contributors, each with 250,000 items or more, are content hubs that provide metadata directly to DPLA, which is a metadata repository rather than a repository of images, books, or any other physical content.

Early partners were already busy gathering digital data for the future of libraries. The participants include the Library of Congress, HathiTrust Digital Library, and Internet Archive.

Late last week, in a two-day meeting, 700 librarians from across the United States and a few from Europe gathered in Boston to see what was new, and to see what was ahead for DPLA. (Donating venues were the Boston Public Library, Northeastern University College of Social Sciences and Humanities, and Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science.)

One new aspect was a nearly $1 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to underwrite digital training for local librarians. (About 1,700 local libraries are plugged into DPLA so far.) Also new was the fact that three data-aggregating partners signed on in New York, North Carolina, and Texas. And DPLA has added features, including StackLife, a digital browsing tool developed at Harvard that allows a user to see at a glance the popularity of a given book.

What was ahead is “much work and many challenges,” said Doron Weber of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, a key early funder of DPLA. The conference, divided into workshops, revealed future needs and action steps.

Among those needs were more service and content hubs, more access to DPLA in local libraries, more connections with library-hungry community colleges, more advocacy volunteers and partners, links to European digital counterparts, “tool kits” for navigating copyright pitfalls, and more diversity in both collections and board members.

Once just a dream

Though a librarian’s dream for decades, a digital library on the scale of DPLA was conceived only three years ago at an exploratory seminar at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. It took the 40 experts in attendance just a few minutes to craft a mission statement word by word, one that’s still in place: to create “an open, distributed network of comprehensive online resources that would draw on the nation’s living heritage from libraries, universities, archives, and museums in order to educate, inform, and empower everyone in current and future generations.”

Then, Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society convened experts to work on a technical and administrative architecture for DPLA. By two years ago, a steering committee was in place at the Berkman. Two key staffers, including Cohen, were hired by the end of last year. Then the wheels were spinning fast. Weber compared DPLA to “a young nation just growing up.”

Now with a permanent staff of five and thousands of volunteers, the DPLA celebrated itself for the first time Oct. 24-25. The initial gathering, a reception and briefing, was in the Boston Public Library, the first large and free municipal library in the United States. It opened in 1854 in a schoolhouse and made 5,000 books and periodicals available for loan. Anyone over 16, with the right character reference, could borrow one book at a time for two weeks.

“New” and “large” apply to the DPLA too. There are Harvard footprints all over the project, but who really started it? “My answer is: It’s collective,” said Robert Darnton, Harvard’s Carl H. Pforzheimer University Professor and University librarian, who convened the Radcliffe seminar three years ago. “Everyone agreed it was a good idea and we would make it happen.”

Transparency and a sense of collective effort still rule, he said of the DPLA, which maintains a distributed, horizontal structure — not something that would work “from the top down.”

In a time of considerable government dysfunction, the DPLA also can provide a lesson in the efficiencies of public-private partnerships. “We don’t go to the government,” said Darnton. “Right here, we can prove we can get the job done.”

He and others resisted hyperbole about the DPLA, which has already drawn comparisons like “the mother of all libraries.” Former Berkman Center Executive Director John Palfrey, a DPLA board member, provided a cautionary note. “What we have is a tiny, tiny starting point,” he said. “We have centuries to go in this project. Honestly.”

The future of libraries is already at hand, according to one breakout session. One of the moderators, Harvard’s Jeffrey Schnapp, challenged those in attendance — approximately 40 in a seminar room at Northeastern University — to brainstorm two ideas in small groups: something immediate and practical, and something futuristic and wild-eyed. Schnapp, a Dante scholar, is co-director at the Berkman Center and faculty director at the metaLAB (at) Harvard.

Sober and futuristic, ideas bubbled up and were captured later on a Google Docs site. Among the ideas were: Use city libraries as portals to city data, from history and crime stats to where storm drains are. Open libraries to DPLA fellowships, so journalists, artists, interns, and writers-in-residence can tell local stories. Open more “maker spaces” in libraries, or move digital libraries to satellite spaces like cafes and town halls.

Giving communities voice

Darnton helped run another session, on how the DPLA can draw more contributions from communities, and in turn can be more helpful to them. “One of the main missions of DPLA is to give voices to communities,” he said.

With him were Kathryn Blackmer and Lillian Castillo-Speed of the Latino Digital Archive Group in California, which illustrated a problem of scale. During a heritage fair that the group sponsored, two people showed up with a few digital photographs to scan, and 90 minutes of stories to tell. “What do we do with what we get?” asked Blackmer. How does something on the scale of DPLA capture moments that small and fine?

“We’ve got a long way to go,” said Darnton, but the service hubs are the key, and the DPLA needs more of them to aggregate metadata from small sources that in the session came to be called “hyperlocality.”

Another key to gathering links and data, local history groups, emerged from the audience of 50 in the Northeastern classroom. One such group is the History Harvest out of the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, whose co-director, Patrick D. Jones, was in the audience. “It’s a unique way to get at those local histories,” he said, and they could be streamed into DPLA-rich vaults of digital Americana.

In a flurry, other models were discussed at the session, including local history initiatives at Northeastern, the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, the University of Florida, and the Maine Memory Network. Gathering oral histories can happen in schools, in libraries, and in community centers, said Jones, who remembered a local center for immigrants. It owned little, he said, but “what they really had was stories.”

“The idea,” Darnton understood, “is to make local communities feel like they’re full partners.” He was happy at the idea of DPLA content at such a local level, and said the History Harvest and others were rich sources for the service hubs gathering metadata.

A theme that rose out of the session on communities involved what the DPLA can do for library-poor community colleges, where almost 14 million adult students are enrolled and where the DPLA should have “a special mission” to help, said CM Winters-Palacio, a professor and director of the library at Malcolm X College, City Colleges of Chicago.

Winters-Palacio summed up the session’s last leitmotif too. “I want to see the (DPLA) board more diverse,” she said of the nine-member group. “It’s not rocket science.”

Darnton said, “The DPLA belongs to everyone.”

Late in the afternoon, Darnton took what he called his “to-do list” and joined other group leaders — and hundreds of librarians — in summing up the day’s ideas, visions, complaints, and action items. Suggestions included getting scholars to contribute metadata directly, bringing in more multimedia, linking to research data, spurring policy debate on licensing and other issues, planning for a DPLA on a global scale, attracting future partners, and targeting scientific audiences.