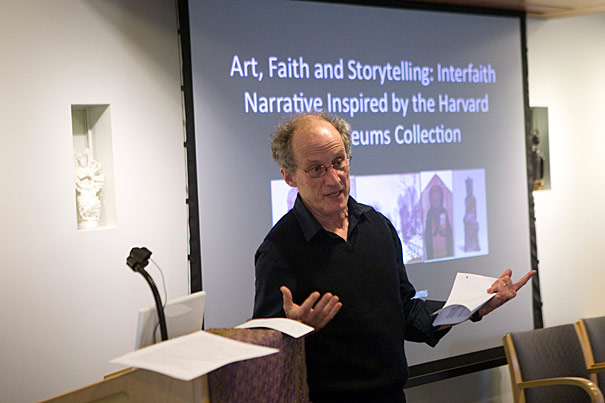

“There’s no visual art in the Jewish tradition that actually focuses on God,” said Harvard Hillel chaplain Rabbi Norman Janis, who called the assignment a challenge.

Photos by Brooks Canaday/Harvard Staff Photographer

Lasting power

Tales of art, faith, inspiration at Divinity School event

An intimate discussion at Harvard Divinity School’s (HDS) Center for the Study of World Religions on Monday (April 11) examined the intersection of art and faith as Harvard scholars shared personal stories inspired by works from Harvard Art Museums’ collections.

“My hope is that these stories will resonate with each of you,” said HDS student Asha Kaufman, who organized the event. Kaufman, an intern in the museums’ education department, and the Harvard speakers together explored the collections to identify certain works that stuck a chord. The scholars then created personal narratives inspired by those works.

This project “awakens the fact that this art, even in a neutral space, brings religious issues back to life,” said Francis Clooney, the center’s director.

An image of a hooded monk conjured up the vision of a motorcycle-riding monk clad in a black leather jacket and boots, and a sacred cardboard box, for Stephanie Paulsell.

The Amory Houghton Professor of the Practice of Ministry Studies chose to focus on the museums’ 13th century statute of St. Dominic by an unknown Italian painter. The depiction of the bearded monk dressed in a dark habit reminded her of a longtime family friend, a Trappist monk who loved his motorcycle. Upon leaving the country to become a hermit, in Papua New Guinea, he entrusted her father with his “box of treasures.”

Inside were sermons, retreat talks, letters, and notes that she remembered poring over as a young girl.

She recalled a newspaper clipping of a picture of a Vietnamese girl whose clothes had been burned off in a napalm attack, and the image of her monk putting on his habit in preparation of a 235-mile walk to Washington to protest the Vietnam War.

The box was also full of letters from peace activists.

“From their letters I learned what passionate commitment sounded like, and received thrilling information about the power of the well-placed four-letter word.”

Paulsell said it was “consoling to remember how much real treasure was packed into that one cardboard box,” one that lifted her heart as a young girl.

I wonder, “Am I filling the box of my life with treasures that would lift a child’s heart?”

The sculpture of an elephant-headed Hindu deity from the museums’ collections inspired Harvard’s Hindu chaplain to examine the wide-ranging impact of the Hindu god Ganesha.

Ganesha was a ubiquitous presence for Swami Tyagananda, who grew up a Hindu in India — one that he took for granted. “Looking at it and thinking about it consciously,” he said, “was a new exercise.”

The image may challenge ideas of normalcy, said Tyagananda, who added that an elephant-headed vision of the divine might appear strange to some. But it may also serve to strengthen the interfaith tradition and the importance of tolerance and understanding.

It reminds us that “what may seem to be very normal and natural for me, need not automatically appear normal and natural to everyone.”

Ganesha, he said, has also transcended the Hindu tradition and been adopted by people of various religions as a symbol of protection and power.

Tyagananda recalled meeting a Congregational minister who eagerly showed him his ring carved with an image of the Hindu god.

“Don’t tell anybody,” the minister said, ”he is very powerful. He has protected me on many occasions.”

The god is also firmly established in Indian pop culture, making him accessible to an even wider audience, said Tyagananda, who played a clip of a hip-hop song devoted to the deity.

“Ganesha makes everything possible,” the musician rapped, “because elephant powers are unstoppable.”

Looking closely at art within a religious context was a difficult task for Harvard Hillel chaplain Rabbi Norman Janis, who called the assignment a challenge.

“There’s no visual art in the Jewish tradition that actually focuses on God,” said Janis, citing the Second Commandment, which prohibits the creation of images of God.

Instead Janis chose to focus on Claude Monet’s “Road toward the Farm Saint-Siméon, Honfleur.” The early work by the Impressionist master depicts a couple walking along a snow-covered lane that curves out of view.

“This kind of thing I’ve always responded to. … It’s the human path that draws me in and then can sometimes lead to an experience of God.”