Sports betting worries grow as wagers skyrocket

Experts see rise in gambling problems, possible wider cultural fallout

Americans have taken an increasingly dim view of sports betting in the seven years since the Supreme Court overturned a federal ban, as online wagers have skyrocketed, igniting concerns over the personal and social costs.

According to a recent poll from the Pew Research Center, 43 percent of U.S. adults say the fact that sports betting is now legal in much of the country is a bad thing for society. That’s up from 34 percent in 2022.

Harvard experts and others suggest that gambling addiction appears to be growing as a public health concern for individuals, and some see the likelihood of wider economic fallout.

Counselors have reported an growing number of patients with gambling problems. And a February study in JAMA Internal Medicine noted that internet searches for gambling-addiction help have risen 23 percent nationally from the 2018 court ruling through June 2024.

“When new forms of gambling appear, the rate of savings go down, then you see the rate of credit card defaults going up. And you see the rate of mortgage defaults going up. So these are long-term financial and societal costs with broad implications,” said Malcolm Sparrow, professor of the practice of public management at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

“Having it on your phone with push notifications and constant advertisements is able to kind of hijack your brain in a really fascinating way. Before, you’d have to drive to a casino, and I think that served as a bit of a barrier.”

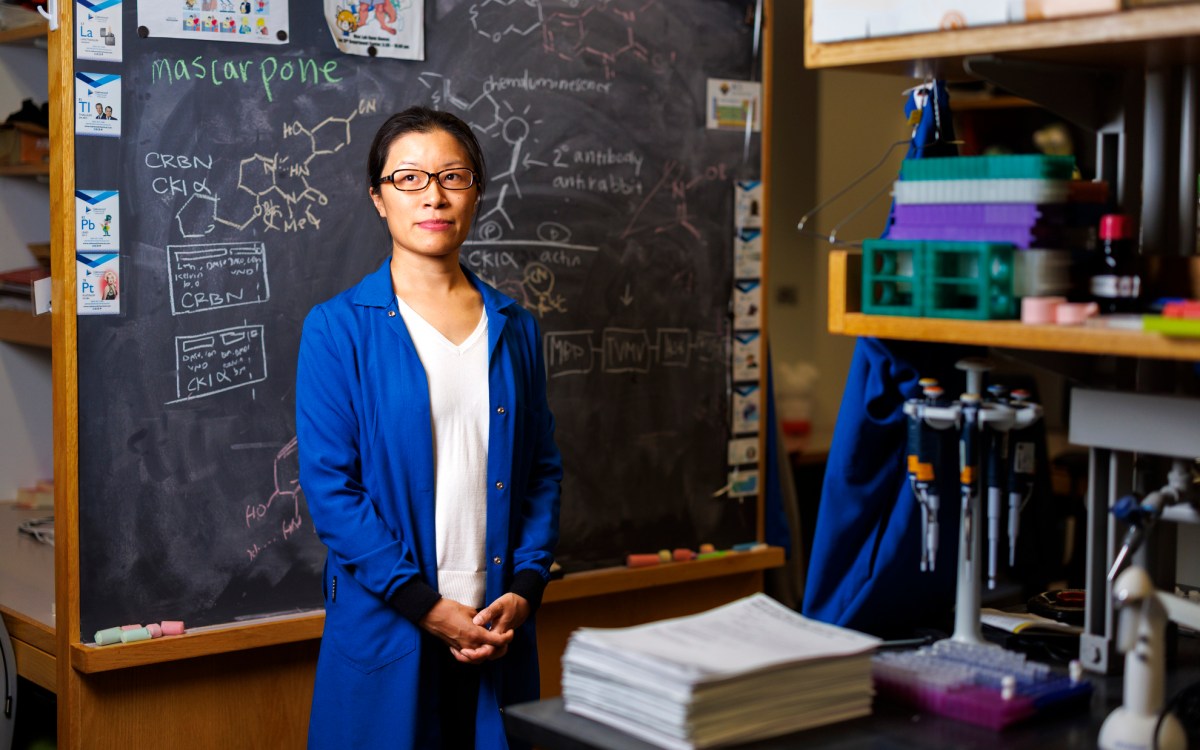

Spencer Andrews

In the U.S., the floodgates for sports betting were opened in 2018 following a Supreme Court decision to overturn a federal sports gambling ban and turn over regulation to state governments. Currently, 39 U.S. states have passed legislation legalizing sports betting in some form.

The JAMA study found that total sports wagers increased from $4.9 billion during 2017 to $121.1 billion during 2023, with 94 percent of wagers during 2023 being placed online.

“It takes between five and seven years before countries become more painfully aware of all the misery that increased access wreaks on public health, public finances, and so on,” said Sparrow, much of whose work involves studying the regulation of societal risks, including gambling.

The initial push for legalization stemmed from a desire for state governments to create an alternate form of tax revenue. Lobbyists for sports betting companies have downplayed the addictive nature of the behavior, experts say.

“It made a lot of sense to do. It was popular, and everyone was going to make money off of it,” said Spencer Andrews, a student fellow at Harvard’s Petrie-Flom Center. Andrews, who spent several years as a research fellow at the National Institutes of Health, is the author of a two-part series for the Bill of Health Blog regarding the dangers of sports gambling.

“I just think it was a short-sighted decision,” he said. “In the end, as ubiquitous as it is now, it’s clearly gotten out of hand.”

In his series Andrews picks up on an aspect of sports betting that, according to psychologists, lends itself to addictive behavior.

“Having it on your phone with push notifications and constant advertisements is able to kind of hijack your brain in a really fascinating way,” he said. “Before, you’d have to drive to a casino, and I think that served as a bit of a barrier.”

Debi LaPlante, director of the Division on Addiction at the Cambridge Health Alliance and an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, said she thinks it may be hard for clinicians to spot and treat negative sports betting behaviors because most have so little experience with it.

“Many healthcare providers don’t have the knowledge, skills, or tools to address gambling-related problems among their clients and patients,” she said.

LaPlante suggests making screening for gambling widely available for healthcare professionals to better connect people to help.

“Sometimes people don’t recognize when gambling is causing a problem,” she said.

Sparrow added that research suggests that even mild participation in sports betting may be harmful.

“We suspect up to 50 percent of gamblers suffer some degree of harm and regret, and a much broader definition say it’s having an adverse effect on their life, and they’ve tried to stop but can’t,” he said. “Now that’s not enough to get you designated as a problem gambler, but it still means it’s having a lasting detrimental effect in one dimension of life or another.”

Some safeguards have been implemented in recent years. Some sports betting apps allow users to set loss limits, and nearly every advertisement for sports betting across the U.S. is accompanied by addiction helpline information.

Andrews added that banning advertising during sports events may help state governments cut down on risky betting.

“It’s kind of like a cigarette brand advertising at a nicotine lovers conference or something. It’s a cheat code,” he said. “At the end of the day, the government owes their consumers a protection from being led astray by private interests. And I think taking a step back and letting anything happen here is just not the answer.”

Sparrow said another strategy is for states that haven’t approved online sports betting to stand firm.

“The industry would like to have us all believe that it’s inevitable all 50 will get there eventually,” he said. “The economic benefits are grossly over-emphasized in the policy debates leading up to legalization or increased legalization, and that’s a deliberate tactic on behalf of the industry.”