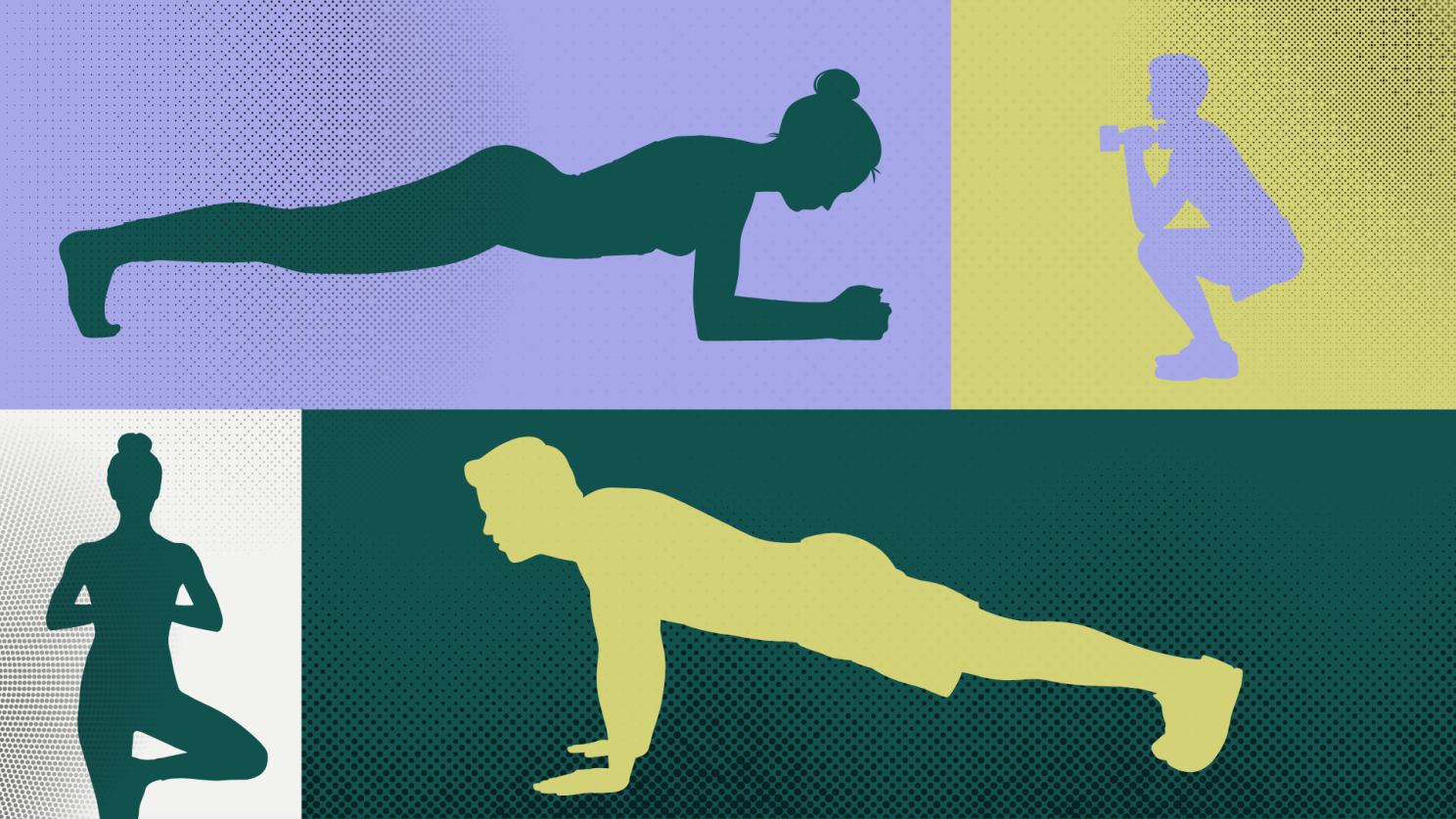

Illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

How to get stronger

If you’re not failing all the time, you’re doing it wrong, says fitness expert

Part of the Wondering series

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Edward Phillips is an associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School and the Whole Health Medical Director at VA Boston Healthcare System.

As Americans, we’re in miserable shape. Only about half the U.S. population meets the Physical Activity Guidelines for cardiovascular activity, which is 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week, and even fewer, less than one in three, meet the recommendations for resistance training, which are to engage in strengthening activities involving all muscle groups at least two days per week. We have much less physical demand in our day-to-day life than we did decades ago, which means we need to be more intentional about physical activity.

But most people haven’t gotten the proper training on how to lift weights, and form does matter. You can get some pretty good instructions just from YouTube videos. I also often refer to physical therapists (who are licensed professionals and usually covered by your health insurance). You can also find a certified strength and conditioning specialist or exercise physiologist, who can meet you where you’re at and prescribe you a course of training.

Here are some tips to get you going:

Anything is better than nothing.

Your body doesn’t know how much money you spent on a gym membership or a personal trainer or if you’re wearing Lululemon: Any stress that you put on your body that it’s not accustomed to, your body will respond and get stronger. It doesn’t have to be dumbbells. Many parts of a standard yoga workout — holding a plank, or a standing pose — are great resistance exercises. Bodyweight exercises, things like squats, push-ups, or heel-raises, can be done at home with no equipment.

Work to failure.

The most scientifically accurate advice is also the worst for marketing: Work to failure. We’re success-oriented creatures; nobody wants to work to failure. But to see maximal results, you want to work to the point where you would not be able to do any more reps. You should aim to be able to do eight to 12 reps before you have to stop. If you can’t make it to eight reps, you probably need to modify your movement or use lighter weights; if you make it to 12 reps and you’re still not struggling, you’re ready to use heavier weights. Another way to look at it is cadence: If you’re slowing down by more than 20 percent, you’re reaching your limit.

Sore? Congratulations.

Now, what if you get delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS)? Good job! That means you’ve successfully worked out. For relief, try heat or cold, compression garments, and over-the-counter analgesics. You can still work out, though maybe at a lesser intensity — or take DOMS as a cue to do a different kind of exercise. Get in the pool, get on a bike, or go for a walk instead.

Both cardio and resistance training are important parts of overall physical health, but there are benefits from resistance training that you won’t get from cardio. People don’t like to hear it, but the natural diminution of muscle mass begins in our 30s, and a stronger body is better able to do fun things, like pick up a grandchild, and to stay independent later in life. Additionally, if you’re on a GLP-1 agonist or on a diet, it’s imperative to do resistance training to mitigate the loss of muscle mass as you lose weight.

Your body is an adaptation machine: The way you stress it is the way that it will respond. So if you want to run faster, you need to run faster. If you want to get stronger, you need to produce stress that is not usual for your body, and your body will respond by getting stronger. In short, the more you do, the more you can do.

— As told to Sy Boles, Harvard Staff Writer