‘It just feels good when you solve the hard problems’

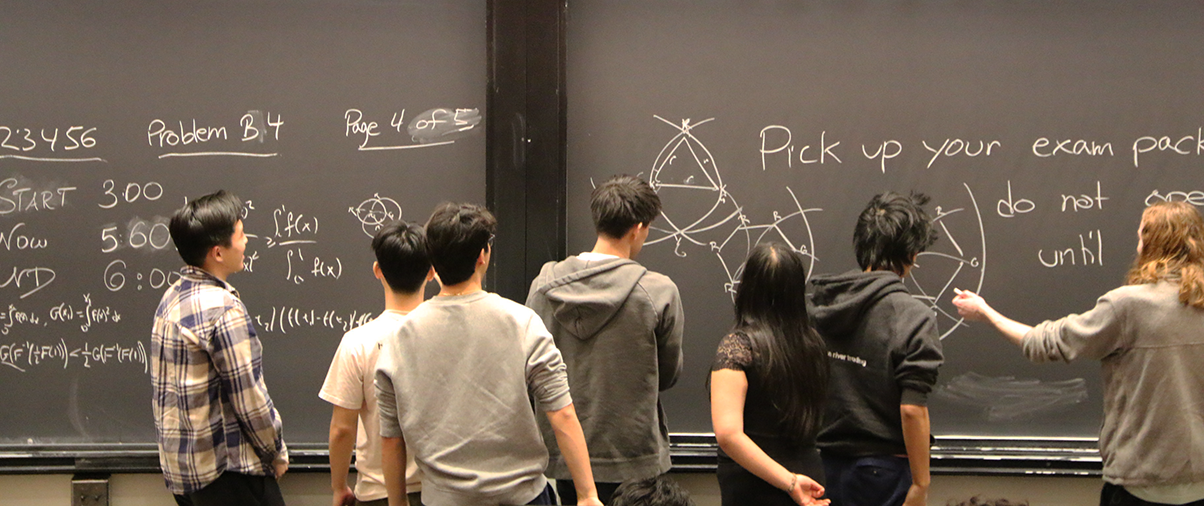

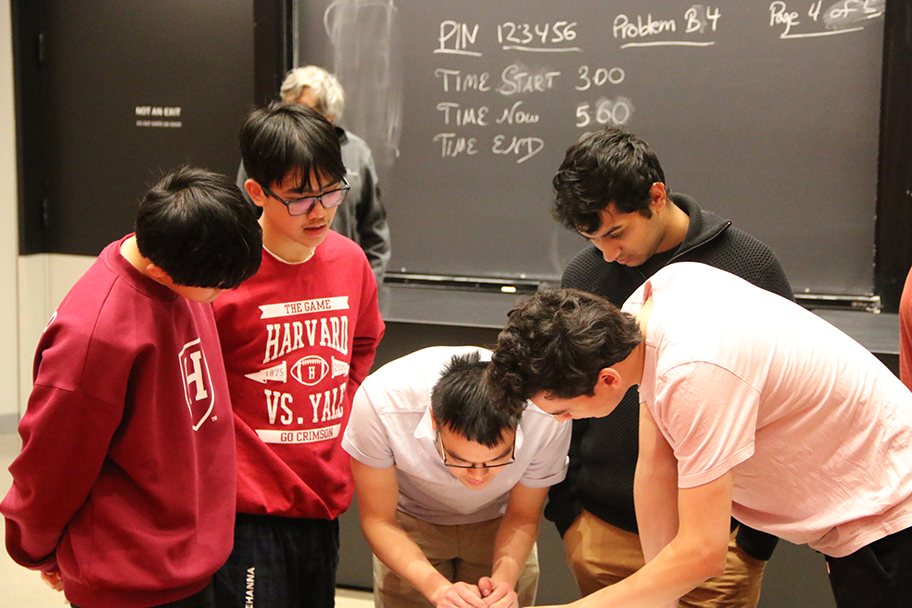

Students compare answers after taking the Putnam exam.

Photos by Megan Martinez

Why do students volunteer to take this notoriously difficult math exam? For the fun of it.

At crunch time at the end of fall semester, Easton Singer ’26 had many things piled on his plate: an orchestra performance, final exams and projects, a senior thesis, and applications for graduate school. Yet he put all that aside to spend a precious Saturday in the middle of reading period voluntarily taking yet another exam — one that had nothing to do with his classes nor any impact on his transcript.

The Kirkland House resident was among more than 50 Harvard students who participated in the William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition, the premier math contest for college undergraduates in North America. Now in its 86th year, the Putnam has a storied history, and many top finishers have gone on to become prominent mathematicians, professors, and winners of Nobel Prizes and Fields Medals.

“I take it just because it’s fun,” said Singer, a math concentrator with a secondary in computer science. “It’s the best chance to do math problems. I get the sense that other people also do it not because of a particular competitive drive, but more because it’s fun and because their friends are also doing it.”

Fun? The Putnam exam is notoriously difficult even for people who normally consider themselves pretty good at math. The six-hour exam has 12 questions worth 10 points each. A perfect score of 120 is a rare feat achieved only five times since the competition began in 1938. Last year, only five students in the world scored 80 or higher. Only 45 people — barely 1 percent of the competitors — managed to get even half the available points.

Among nearly 4,000 students in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico who took the exam in 2024, the average score was only 8; half of the test-takers scored 2 or lower. Results for the 2025 test will be released around February.

Contrary to common assumptions, the test does not require much higher-level math, although some can be helpful. But it does test problem-solving ability, time management, and mathematical intuition for shortcuts that can quickly arrive at short proofs — and bypass more laborious, time-consuming routes to the same answers.

“It just feels good when you solve the hard problems,” said Andrew Gu ’26, who has twice finished among the Putnam’s top 16. “In some problems, discovering the little trick that they put in there just feels magical.”

“In some problems, discovering the little trick that they put in there just feels magical.”

Andrew Gu

Historically, Harvard has the most first-place and top-five finishes in the team competition. In recent years, however, MIT has dominated the Putnam. Last year, our crosstown rivals claimed 69 out of the top 100 finishers and the entire top five (who are honored as “Putnam Fellows”) for the fifth year in a row.

In the 2024 team competition (the sum of the ranks of the top three finishers at each school), Harvard finished second with a team composed of Gu, Kevin Cong ’26, and Eric Shen ’25. Harvard last won in 2018 and has placed second behind MIT in four of the last five years.

“It’s worthy to note how well Harvard does despite the lack of departmental-organized practices and training, especially against large universities that hold Putnam workshops and classes,” said Cindy Jimenez, the undergraduate program coordinator for the Department of Mathematics.

MIT places greater emphasis on the Putnam and offers a preparation class for credit. In contrast, the Harvard Department of Mathematics has made a deliberate choice not to push the exam or organize any official prep sessions. Aside from advertising the event and handling registration, the department hosts only one event related to the competition — a “Putnam Postmortem” to review the questions on the last exam led by Professor Noam Elkies, who was a three-time Putnam Fellow as an undergraduate at Columbia in the 1980s.

“I think it makes sense to de-emphasize competition mathematics,” explained Elkies. “As one progresses from grade-school math to college and beyond, one moves further from the domain of competition problems that are guaranteed to be solvable within an hour or so under the constraints of a closed-book exam.”

The exam is held in early December, typically a busy time for Harvard students during reading period at the end of the semester.

Cong has never missed a Putnam.

“It’s sort of a fun hobby,” he said. “It’s also somewhat nostalgic, having done that stuff in the past.”

Cong became interested in math as a child after discovering some math texts and series of books on math topics called “The Art of Problem Solving.” He found he was good at math contests, won numerous competition medals, earned invitations to national training camps, and a spot on the 2022 USA team for the International Mathematical Olympiad, where he won a gold medal, alongside Gu, who won silver.

The tournament chops mastered in high school continue to serve him well. Like most of his Harvard friends, Cong doesn’t do much preparation for the Putnam. This year his only departure from his normal routine was going to bed and rising a bit earlier than normal before the test.

“Not many people here, as far as I know, do it seriously,” said Cong, a math and statistics double concentrator who finished in the top 25 of the 2024 Putnam. “I think most people just view it as a cool competition that they can spend six hours of their Saturday doing once a year. They’re really cute problems.”

Likewise, Singer did not do much preparation. But he too is steeped in the subject: He did math competitions during high school, serves as a course assistant for classes such as Math 55, and co-authored a paper titled “Factorization in Additive Monoids of Evaluation Polynomial Semirings.”

“I just woke up early enough so I could be awake by the time I got here,” he said after the exam. “Also, so I could eat breakfast, which I don’t normally do.”

“I did not successfully eat breakfast!” Cong chimed in with a laugh.

After the exam, the Science Center hall buzzed with energy and bursts of laughter as students gathered to compare answers. Some wrote solutions on the chalkboard. There were a few palms slapped to foreheads when people realized solutions they had missed.

“It was really cool seeing other methods people use, because there are so many different ways to get the same answer.”

Matteo Salloum

“It was really cool seeing other methods people use, because there are so many different ways to get the same answer,” said Matteo Salloum ’28. “It’s very illuminating, because math is very collaborative. It’s very interesting to see the ways different ways people take to get the solution.”

Singer — who was taking the exam for the fourth and final time as a Harvard student — felt content. “I’m happy, because I think solved six in total,” he said, expressing hope that he had managed to achieve his best score yet.

Then he looked at the clock.

“I should not be here right now,” he said. “In fact, I need to go to rehearsal — Harvard College Opera. I’m playing the piano.”