Tracy K. Smith thinks poetry could help bring us together, if we let it

Two-time U.S. poet laureate recalls her national project to encourage ‘notion that your life must be as important to you as mine is to me’

Photo by Andrew Kelly

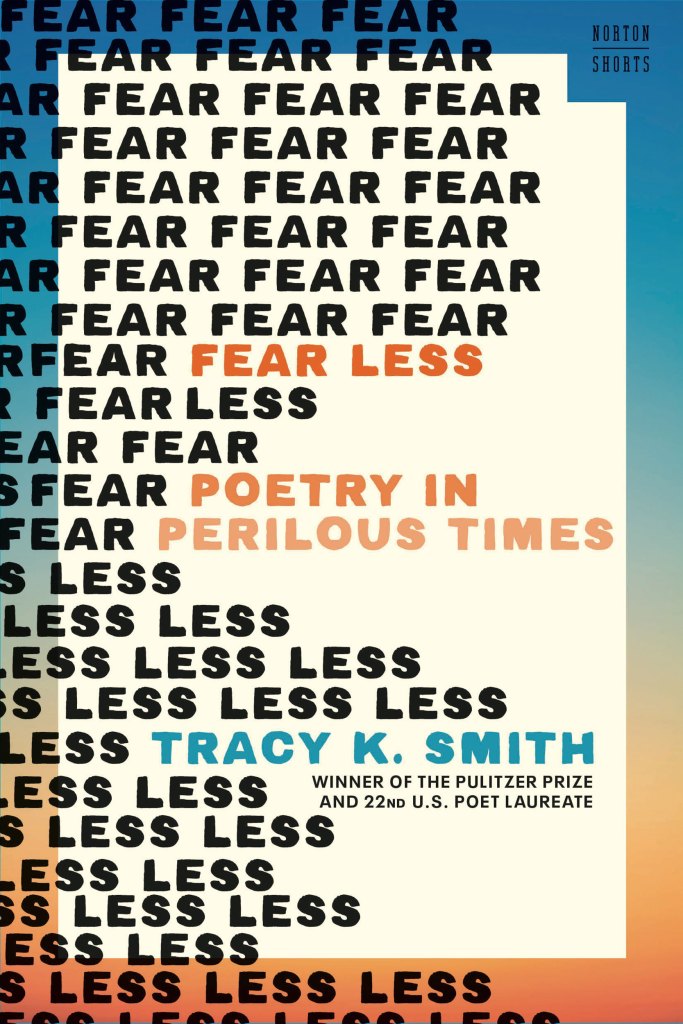

Reprinted from “Fear Less: Poetry in Perilous Times” by Tracy K. Smith ’94, Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory, professor of African and African American Studies, Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

In 2017, I was appointed poet laureate of the United States by Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. The opportunity to act as an ambassador between the art form I practice and the nation to which I belong came at a delicate time in American history. Maybe all times are delicate, but by 2017 we’d come to find ourselves in a climate of language — I’d call it a national vocabulary — grounded in fear, derision, and the notion of an intractably divided nation. The guardrails of courtesy were gone, and the limits of shame — or was it shamelessness? — had been set further out than almost ever before. Or so it felt. At the same time, so much talk — on podcasts and radio and TV — added unceasing fodder to the rumor that unless we lived in the same place and prayed to the same deity and voted the same way, we in this country had nothing whatsoever to say to one another. It was a bruise on the collective imagination, a threat to the sense of hope and possibility.

But I thought about the poems my students and I discussed with one another each week. The near-holy hush in the room as we read aloud from the work of poets like Elizabeth Bishop, Gwendolyn Brooks, Robert Hayden, and contemporaries Claudia Rankine, Natalie Diaz, Patrick Rosal, and others. It wasn’t only delight that held us in such a state; it was the desire to listen at the widest possible angle, and the proper tilt of the imagination, in order to catch what the voice on the page was asking us to hear, feel, see, remember, and recognize. At such a pitch of attention — which is not passive but active — so much of your energy is invested in maintaining the signal that another voice is transmitting. You may have questions. Doubts, eventually, too. But in good listeners, those things emerge as the result of having first submitted fully to the voice and the imagination before you. Considered in this way, the audience of a poem is undertaking something like a trust-fall. Come what may, we are ideally willing to say to the poem, I’m here, I’m in your hands.

This isn’t, generally speaking, the mode in which we dwell. It’s not the way we go about gathering the information that informs so many of our small and large decisions. It’s certainly not the way we tend to take in another person’s opinion about sports or parenting or politics, where our listening is tense as we await the chance to launch our own argument or defense. Almost daily during the long and histrionic news cycle leading up to the 2016 election, I had found myself thinking, Poetry wouldn’t allow us to behave this way. I just knew that poetry, a kind of mother to so many, would find a way to jostle us out of our rote engagement with one another. Poetry would insist that our listening be permitted to lead us, even briefly, out of our rigid stances, our staunchest habits. Already I could hear Mother Poetry saying: Come. Sit. Calm yourselves and attend more generously to one another. So when the opportunity arose to create a national poetry project with the Library of Congress, I determined to push back against the inescapable narrative of America as a divided nation — the narrative that says people in the rural heartland have next to nothing in common with those of us in urban centers, and that differences of race, class, religion, and citizenship status had sawed us into a puzzle that would never be pieced back together.

I also wanted to test out my own theory that Americans of all backgrounds might have something quietly urgent and humanizing to offer to one another, if only we could turn down the volume on all the many sources seeking to sell us on the notion of an unmendable divide — to hook us on a product, which is strife. In order to get to community, we have to go quiet, slow down, allow ourselves to be both vulnerable and brave, and approach one another with an idea as simple as, I’m me, you’re you, we are not the same, and yet perhaps we can feel safe here together talking about something as simple as a poem, which encourages the notion that your life must be as important to you as mine is to me. If we let them, poems also encourage the more difficult notion that your life ought to be as important to me as my own life is; that I can only truly honor and protect myself by honoring and protecting you.

That was my theory. And what I found, on each of the trips making up the national poetry project, which we ended up calling American Conversations, was wildly heartening. We hosted events in public libraries, community centers, rehab facilities, detention centers, churches, retirement homes, and theaters in Alaska, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, New Mexico, South Carolina, and South Dakota. We passed out copies of American Journal, the anthology I edited for just such a purpose during my time in the laureateship. And then, we’d do the simplest thing: We’d read poems to each other and talk about what we noticed, remembered, wondered, and felt. And we found our way to a counter narrative of careful listening and mutual respect as fostered by poetry. Poems proved to be amazing tools for reminding us of the things we share while also highlighting the differences between us, advocating implicitly for the validity of our differing perspectives.

A nine-year-old girl in New Haven, Kentucky, came by herself to a Saturday morning conversation at her local public library, her home away from home. She sat in the front row with a house key on a string around her neck. She stared up toward the seam between the ceiling and the wall the way children sometimes do when they’re thinking. Or she’d look down at her feet or her lap, but not idly; there was still a kind of attention operating within her body. When she turned to face whoever was speaking, it was as if she wanted to make sure nothing was lost or intercepted on its way to her. Adult women spoke frankly about their memories and their hopes. It was different there now than it had been for them growing up. That this is true of most every place doesn’t solve the dilemma of how to accept change, and whether or when to push back. How to mourn a loss that comes as an effect of opportunity. What to hope for your kids. When finally she raised her hand, the little girl asked, “When did you realize you had stories to tell?” I told her I was just about her age when I wrote my first poem. Then I asked her, “Do you feel like you have stories to tell?” She nodded and told us one about a teacher in her school. A story — perhaps she realized this then, or has by now, or soon will — about change and loss, pain and need. “You can grow up to be a writer if you want to,” I told her. And she nodded, then went back to her listening, which, now that I’m telling it, was exactly how a writer listens.

After an event at Old Summerton High School in South Carolina, one of the public schools desegregated by the US Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, Black members of the first integrated graduating class described how they had written poetry back when they were students, and how the poems we’d read and the experience of talking about them with each other had inspired them to reclaim the practice. “I used to fill notebooks,” one woman said, and her hands floated up toward her chest as if she was holding one again. How much gets poured onto a page, into a notebook? And how much realer to herself might a person become on the heels of such an act?

A man in the audience at a similar session I was invited to host in Jackson, Wyoming, raised his hand midway through a conversation to nearly shout, “I get it! When you read a poem, you’re just kind of pouring it through your own filter to see what gets caught there. My filter is different from your filter. And different things will get caught in your filter at different times, depending on who and where you are when you read the poem.”

Soon after we’d handed out copies of American Journal in a juvenile detention center near Juneau, Alaska, a teenager interrupted to ask if we could please read a poem called “Reverse Suicide” by Matt Rasmussen. Just a few moments with the volume in his hands, and it was as if the poem itself had sought him out, offering to provide a fresh vocabulary for talking about the hardest parts of a life.

I will never forget the profound uncertainty I felt at a home for veterans and pioneers about an hour outside of Anchorage, Alaska. Apart from one or two members of the audience, nobody volunteered to speak. I would read a poem, and it would be followed by a longer-than-was- comfortable silence. Sometimes as I was reading, an audience member would audibly groan. It wasn’t a reaction I was used to, and it was difficult at times to sit with the long stretches of wordlessness. But afterward, staff members were elated. It turned out that a sizeable portion of the audience was made up of nonverbal residents of the facility’s Alzheimer’s unit. Those moans and the inaudible movements that accompanied them were concrete indicators of the ways poems had spoken to and gotten through to audience members. Without realizing it, I had been in the presence of a remarkable response to the power of poetry. One thing that has stayed with me from that evening is the realization that the success of such a project didn’t hinge upon me performing well or hitting it off with people in these different places; rather, it was about giving people space to engage with poems in their own ways and in the terms most meaningful for them.

There is no formula for reading and responding to poetry. How could there be when the lyric tradition exists in celebration of the individual self and its singular experience of the world? The earliest lyric poems were songs for a single voice. Not the sweeping epics of heroes at war or stranded at sea, but intimate accounts of life’s most memorable feelings. Sappho, whose ancient Greek fragments survive from as early as the 7th century BCE, and who would have sung them to the accompaniment of a lyre, bears witness to the particular terms and dimensions of an individual life within the frame of a single moment:

A Girl in Love

“Oh, my sweet mother, ’tis in vain,

I cannot weave as once I wove,

So ’wildered is my heart and brain

With thinking of that youth I love.”

Perhaps a detail like “I cannot weave as once I wove” offers you just enough of a window into the young speaker’s life for you to recognize her hands idle at the loom, and her thoughts adrift in new longing. Whatever it is that draws you in, this momentary brush with a stranger’s experience also gifts you with a remembered or an imagined or a wished-for piece of your own. Her heart racing with anticipation carries over for a moment into you.

Almost three thousand years later, it is still a poem’s speaker who calls to us from the frame of their singular experience. And what we seek in granting them our attention is decidedly not the formulaic, unthinking motions of a prescribed and unchanging rite. No, even when delivering verse in its most methodical traditional forms, like the sestina or the haiku, poetry resists the formulaic in its bid to reawaken us to the miracle and the mystery of our lives. But much of the anxiety surrounding the art form seems to stem from the worry that there exists an authorized way in which a poem ought to be read, and that to set out without such a code of conduct is to be doomed from the outset. One of my hopes is to help put such a notion to rest.

How, then, should you go about reading poems? As you might read a letter from a friend, paying eager attention and trusting that much rides on each word. As someone who has lived most of my life reading, writing, and thinking about poetry, I know there are many points of entry for every poem. Trust the one that speaks to you, and follow where it leads.

Having witnessed how the simple act of reading and talking about poems with others can lead to a sense of trust and ease with one another, I’m left wishing we could make more space for exactly that in our classrooms, in our day-to-day lives, and in the culture we steward together. I wish we could let go some of the need for certainty and the desire to demonstrate our own authority in our interactions with the world. I wish we could abandon the impulse to judge, rate, and rank like incorrigible consumers and instead, together in whatever versions of community we can muster, allow ourselves to wander the wilderness of new feelings — and old feelings in new forms.

Copyright (c) 2025 by Tracy K. Smith Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.