Life and times of ‘the birth certificate of the U.S.’

Professor David Armitage with Anne Sun ’29, Sarah Jiang ’29, and Yasmim Barros ’29 at Houghton Library.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

First-years spend semester delving into 1770s texts, influences that shaped nation, its founding document

“We can call it the birth certificate of the U.S.”

David Armitage, Lloyd C. Blankfein Professor of History, was guiding students back to the world of 1776 as part of his “Declarations of Independence” course, which turns a wide-angle lens on the one-page document that revolutionized global politics, starting in the very nation it announced.

Armitage, author of “The Declaration of Independence: A Global History” (2007), situates the document on a continuum of international calls for rebellion, secession, and natural rights. His syllabus traces its intellectual forebears to the 14th century. The first-year seminar also features analyses and appreciations dated as recently as 2015.

“A birth certificate is an official document which includes the name of the new baby,” Armitage continued. “This is the first public printed document in which the very words ‘United States of America’ appear.”

“This is the first public printed document in which the very words ‘United States of America’ appear.”

David Armitage

The semester’s first few weeks were spent digging into letters, pamphlets, and addresses produced around the time the U.S. took its first breaths as an independent republic.

The “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking Up Arms,” published by the Continental Congress in July 1775, outlines the familiar grievances — on taxes, trade, and military aggression — that had driven the colonists to violence in Lexington and Concord earlier that year.

Soon, the congressmen were logging 12-hour days from their base in Philadelphia, running a military campaign against the world’s leading superpower while laying the foundations for an entirely new way of governing.

“Today we think the outcome was inevitable,” Armitage said in an interview. “But it all could have gone badly wrong. I try to recover that sense of impending doom at the same time as flourishing possibility.”

The founding of the U.S. is top of mind as the country nears a big milestone in 2026. “I wondered about teaching this course in the spring,” shared Armitage, who last offered the curriculum to College first-years about 10 years ago. “But now these students can be experts in time for the 250th birthday next year.”

At the course’s first session, 11 first-years shared their motivations for applying to the course.

Air Force ROTC student Anne Sun ’29 of San Marcos, California, was among those expressing an interest in government and democratic stewardship.

“Knowing my service to the country, I really wanted to understand its roots and ideals,” she later said.

Others were primed by 21st-century cultural products. Credited as inspiration were Nathan Hale’s “Hazardous Tales” graphic novels, the PBS animated series “Liberty’s Kids,” and of course, the Broadway musical “Hamilton,” which just celebrated its 10th anniversary.

“‘Hamilton’ has been vital in animating a sense of how alive and current and engaging the founding period can be,” Armitage said.

The British-born, naturalized U.S. citizen first turned his attention to the Declaration of Independence circa 2003, a time of increased isolationism in U.S. politics.

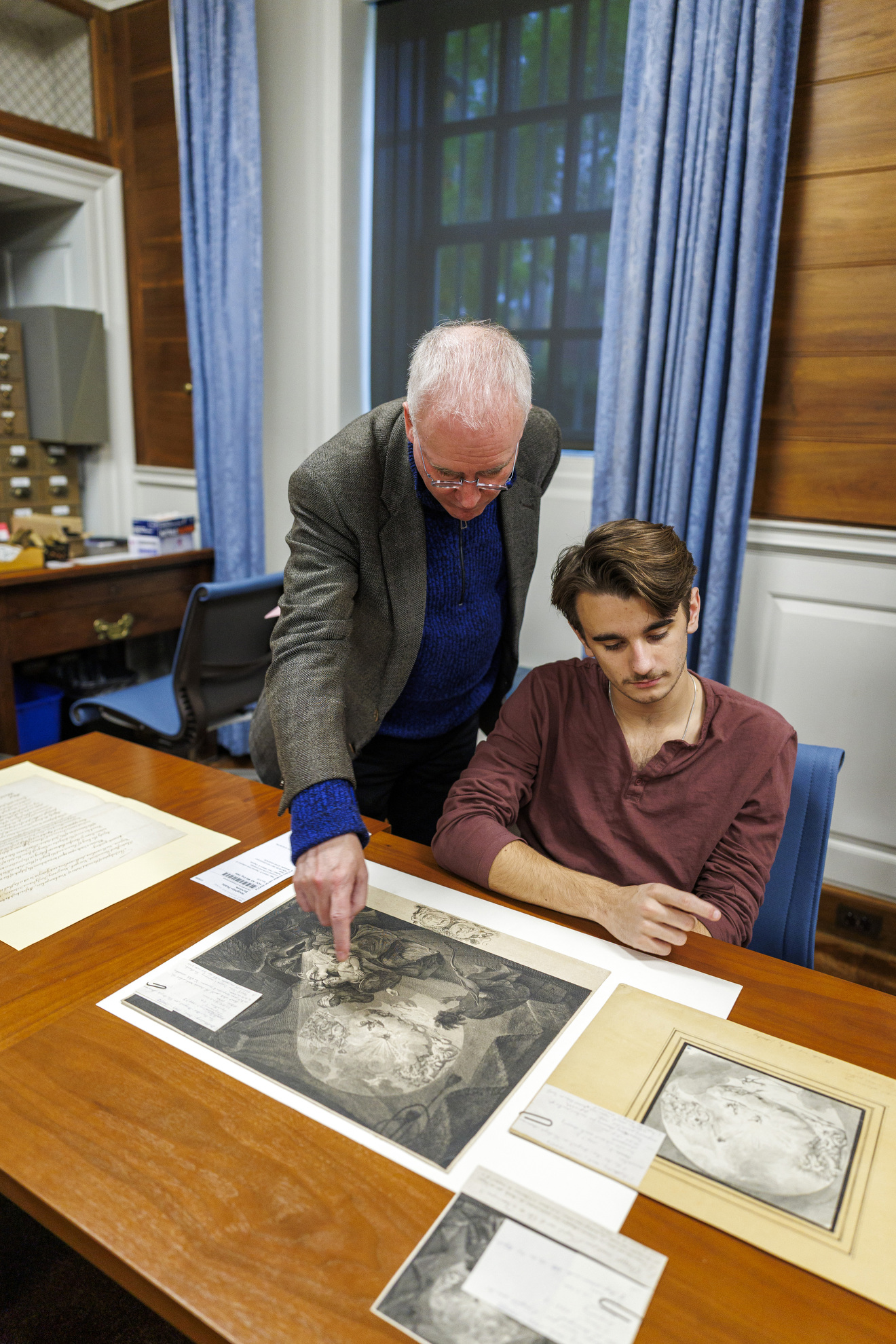

Armitage with Jackson Barr ’29 looking at the William B. Osgood Field collection of European prints and drawings.

A detail from the print.

Chuka Okwumabua ’29 (left) and Mark Guzelian ’29 study volumes from the collection.

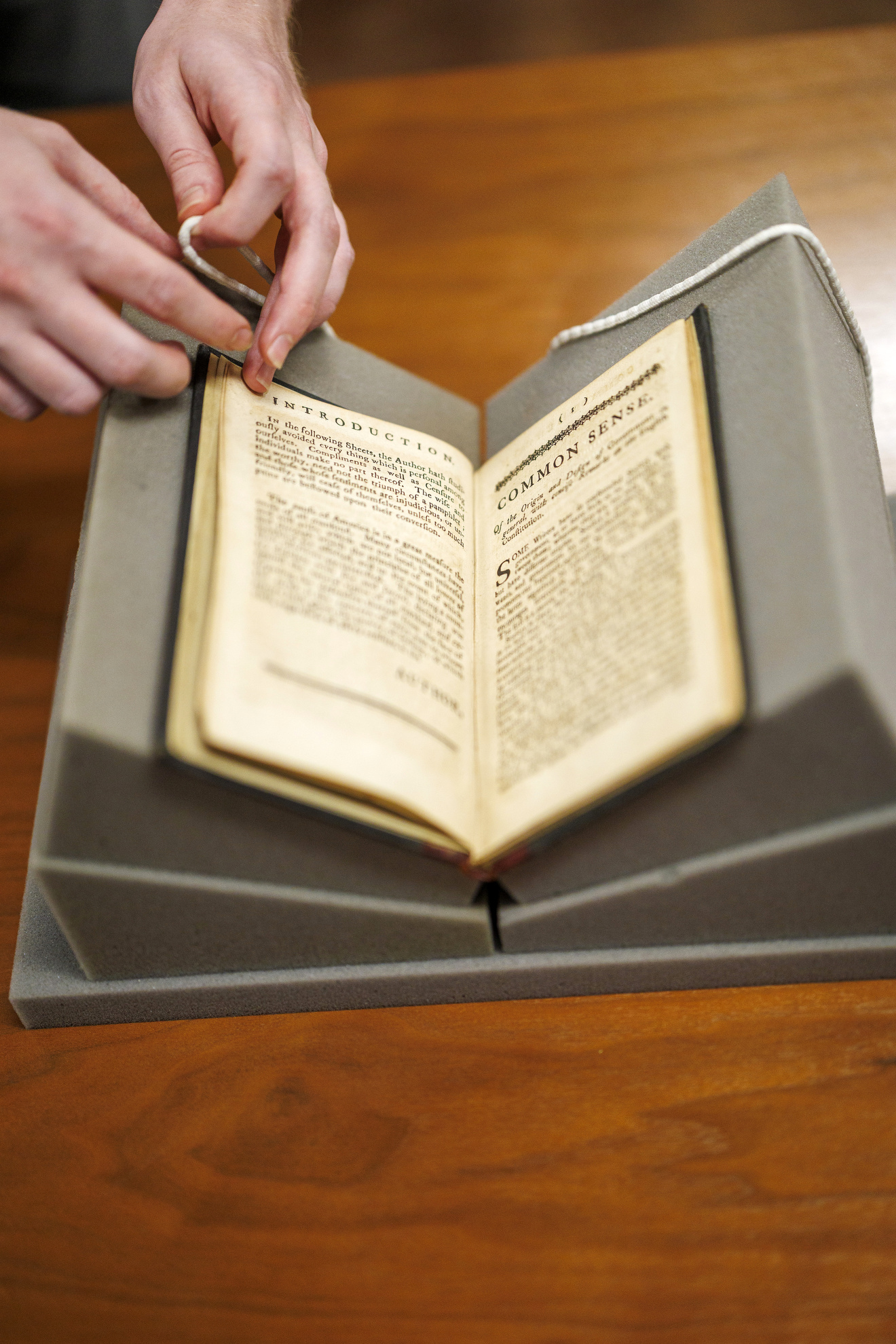

Thomas Paine’s pro-independence “Common Sense” pamphlet.

“I felt very strongly that it was imperative to globalize American history,” Armitage said. “My claim was that if you could show that for the single most important, prestigious, and resonant statement of American values at the very moment of the United States’ birth, then you could globalize pretty much any other aspect of American history.”

His scholarship showed Thomas Jefferson, primary drafter of the Declaration of Independence, to be an adherent of a style typical of the era’s diplomats. Residents of the 13 colonies saw their belonging in a world of deeply interconnected trade and empire. The document’s assertion of state rights would have been paramount.

Eighteenth-century white Americans were less concerned with the “self-evident” truths that helped propel later struggles for racial and gender equality, though African Americans of the time were quick to see the promise.

“The document’s major purpose was putting up a shingle to the rest of the world and saying three things,” Armitage explained. “No. 1, we’re open for business. Two, you can make alliances with us. Third, we are going to be good members of the international community, and we will respect its laws and its rules.”

The 1,400-word Declaration is arranged into five sections, with its poetic statements on liberty and equality situated in the second. The third and longest section functions as a charge-sheet against King George III. As Armitage explains in his book, the climactic accusation concerning “domestic insurrections” features coded 18th-century language suggesting the monarch had encouraged uprisings by enslaved Black populations. It’s packaged with more overtly racist phrasing condemning Britain’s alliances with Indigenous North Americans.

“They did consciously profess liberty, justice, and equality while still hindering the liberty and equality of people of color,” observed Chuka Okwumabua ’29 of Atlanta. “But they recognized this hypocrisy; they were not naïve. Jefferson talked about the fact that in the future there would be more progress and equality for all.”

Learning about 1776, in the language of 1776, upends romanticized notions of U.S. history.

“I had no idea that the colonists thought of themselves as fellow British citizens who really wanted reconciliation before independence,” Sun said. “I didn’t know that the British king forfeited his right to rule, that he was the one who declared Americans to be rebellious.”

The uneven reach of Europe’s great Enlightenment-era thinkers also surprises.

“I always thought the Founding Fathers were all reading the same texts,” Okwumabua said. “In actuality, there was a societal consciousness being developed across mankind during this period, with people from all around the world coming to share certain ideas.”

The U.S. may have formalized the world’s first Declaration of Independence. But it was hardly the last. Armitage’s quest to globalize American history has also meant tracking the document’s impact across five continents.

“I’ve found about 140 or 150 other declarations of independence,” he told the class. “In fact, more than half of the countries now represented at the United Nations have a document they call a declaration of independence.”

Students saw for themselves during a whirlwind visit to Philadelphia to catch the Museum of the American Revolution’s “The Declaration’s Journey” exhibit, for which Armitage served as a consultant.

The show, mounted in celebration of next year’s 250th, features an original 1776 broadside as well as objects connected with declarations of independence for Haiti (1804), Chile (1818), Mexico (1821), India (1947), and more.

“To see that the formatting, the wording, was almost a direct replica of our Declaration of Independence was incredibly inspiring,” Sun shared.

A special viewing was also arranged at Houghton Library, which holds one of 24 known surviving copies from the Declaration’s original printing.

Also displayed for the class were other Revolution-era objects, including a first edition of Thomas Paine’s pro-independence “Common Sense” pamphlet and John Hancock’s July 6, 1776, letter to a Boston-based general, instructing him to read the Declaration to troops on Cambridge Common.

The general public will be able to see some of these treasures when Houghton opens its own semiquincentennial exhibit next summer.

“I like to introduce my students to the physical forms in which these ideas and documents originally circulated,” Armitage explained. “I want them to see, oh, a broadside, single sheet of the Declaration is very different from a little book.”

America’s birth certificate appeared downright modest, its proportions akin to a placemat. A burst of rust-color stains cloud the document’s title. Wrinkles show where it was once folded, perhaps for placement in a pocket.

Yet the ideas it articulates, in tiny lettering, keep changing the world.

“It’s sobering to realize that the founders weren’t these gods, these deities who created a perfect nation from scratch,” Okwumabua said. “They put some of the pieces in place. But we, as contemporary Americans, have equal power to continue that legacy.”