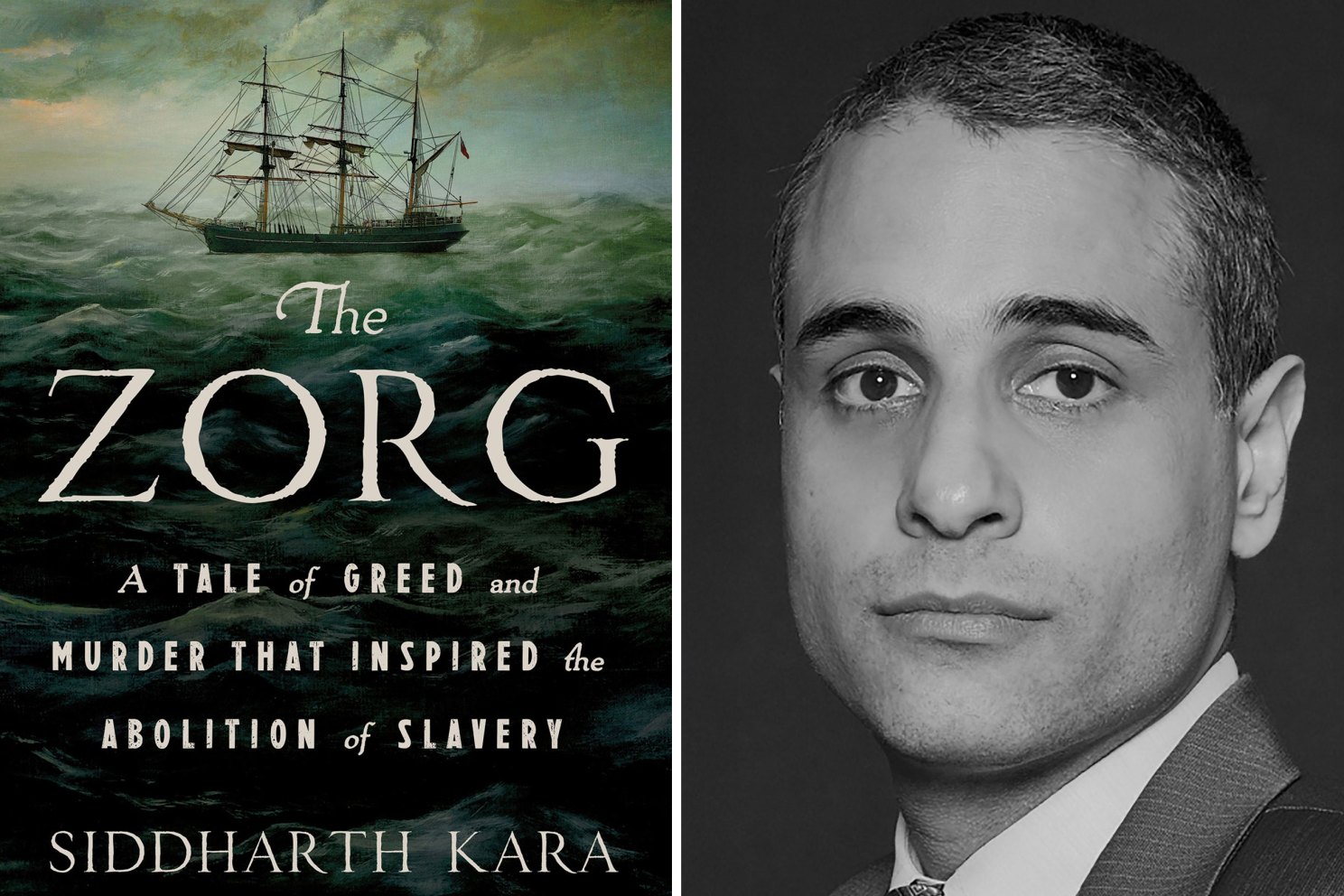

Horrific massacre that fueled drive to end slave trade

Photo by Lynn Savarese

New history traces nightmare voyage, high-profile British trial over insurance claim to collect for jettisoned ‘cargo’

Excerpted from “The Zorg: A Tale of Greed and Murder That Inspired the Abolition of Slavery” by Siddharth Kara, Harvard Kennedy School fellow, ’13, ’16-18, T.H. Chan School of Public Health fellow, ’12-’24

Newly appointed captain Robert Stubbs had wagered that he could reach Jamaica in time. The stakes included the lives of everyone on board the Zorg, the profit of the venture, and the futures of men like the incapacitated captain and physician Luke Collingwood, deposed navigator James Kelsall, and Stubbs himself. Stubbs prudently followed the strong northwest trade winds toward his destination. Laughing gulls and tricolored herons accompanied the ship as it glided over the balmy Caribbean waters.

Two or three days past Tobago, “on or about the twentieth or twenty first of November,” someone on board the Zorg made a surprising discovery. Perhaps one of the Dutch crew members who was used to a more methodical monitoring of provisions under the printed instructions provided by the MCC, the Dutch slave-trade enterprise, to former captain Jan Wilton finally decided to conduct his own examination of the ship’s supplies. Or, like so many other incidents that impacted the Zorg’s journey, it may have just been a random event. Whoever it was, one of the sailors on board the Zorg uncovered that the previous check of the water supply made back near Tobago had been inaccurate.

At some point during the journey, perhaps during a bout of violent weather, “a large quantity of the water had leaked from the lower tier of water casks.” Were these the casks that had been loaded back in Accra when the cooper was ill, and if so, were they not properly trimmed and prepared by the native coopers? Or did they just get damaged at some point along the way? Upon the discovery, the crew conducted a more careful survey of the water supplies, which revealed that there were only “twenty butts of water remaining.”

Twenty butts amounted to about 2,400 gallons of water. Assuming the same consumption rate of 0.5 gallons of water per person per day and 392 people on board (380 slaves + 11 crew + 1 Robert Stubbs; baby of enslaved mother Sia would be nursing), the ship had a 12-day supply of water on board. Given that the Zorg should have been no more than seven or eight days from its destination, the crew could feel confident that they had “a sufficient quantity” of water “to last the voyage to Jamaica.” The discovery of the water leakage was a surprise, but not a catastrophic one.

Prudence dictated an obvious step. Any experienced captain would have taken it. Robert Stubbs should have ordered everyone on board put on a “short allowance” of water. In the event the journey to Jamaica took longer than anticipated or there was some other leakage or loss of water, ordering the crew and Africans to one-half or one-third water allowance would extend the duration of the Zorg’s water supply while maximizing survival rates. Everyone on board would be thirsty, but they would survive.

Robert Stubbs took no such step. If Collingwood or Kelsall suggested it, he didn’t listen. The crew of the Zorg had failed to check water supplies even once during the journey. When they finally happened to notice a leakage, no one did anything about it. The Zorg sailed into the heart of the Caribbean Sea with no land in any direction for hundreds of miles. Day after day of nothing but blue. The ship’s routines almost certainly broke down. There would be no more washing of slaves, emptying of buckets, or adequate time on deck for fresh air. The ship would have been in a state of distress. The sickly, exhausted crew were doing just enough to survive. Collingwood remained incapacitated to the point of lunacy. Kelsall remained confined to quarters. Scurvy and dysentery ravaged the ship. Stubbs drove the vessel onward in a desperate bid to reach Jamaica in time.

On November 27, 1781, with only a few days of water remaining, the Zorg finally spotted land. The ship had traveled nine days since Tobago. It had to be Jamaica, but they needed to be sure. The only other possibility was the adjacent island of Hispaniola, which consisted of the French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti) and the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo (modern-day Dominican Republic). The Zorg faced the same dilemma as it did near Tobago. If they landed in enemy territory, the journey would be a financial failure, and the crew might be detained. They had come too far to take the risk now.

To determine which island they had spotted required a measurement of longitude by dead reckoning. Ideally, Stubbs had been taking longitude measurements every six hours since the ship passed Tobago. It is possible that a delusional Luke Collingwood had been crawling out of his cabin to take the readings, although it is unlikely. Given the enormity of the stakes, he would have relied on abler navigators to take the readings, or at least double-checked his readings with them, especially given how unwell he was. Collingwood was as desperate as anyone to reach land, as he would have been anxious to return home to his family. Out of his own survival instinct, Kelsall would have taken the readings had he been asked to do so, but he remained confined to quarters. The only other person on board with sufficient navigational experience to take the readings, a man who had captained more than one ship across the Atlantic, was Robert Stubbs.

It was most likely Robert Stubbs who dropped the knotted rope and log into the Caribbean Sea on November 27, 1781, to take the longitude reading. He either backtracked this single reading for the entire course since Tobago, or he added it to whatever readings he might have been taking since Tobago. Either way, the reading came back as “74 degrees west,” which placed the ship near the southwest corner of the island of Hispaniola. Latitude put the Zorg as “south nine leagues” (27 miles) from the island. The positional readings indicated that Jamaica was one more day to the west.

The Zorg sailed west. One day later, Jamaica was not to be found. After a second day of sailing, Stubbs sent a sailor up the ratlines, but he was “not able to see land from the foretopmast head.” The longitude reading by dead reckoning had been dead wrong. They had not been south of Hispaniola at all but of their intended destination of Jamaica and that, too, the western edge of the island. Had the reading been accurate, the Zorg could have docked safely in Kingston or whichever port was closest. Instead, the “strong currents which drove [the Zorg] with great rapidity” for two days meant that on November 29, 1781, the Zorg was “distant from Jamaica about three hundred thirty miles.”

To reach Jamaica, the Zorg would have to turn back and sail into the prevailing trade winds. At an optimistic pace of thirty to thirty-five miles a day, which would require expert use of the lateen sail, it would take the Zorg about ten days to reach Jamaica. However, the “few white people … on board were weak and sickly and unable to work the said vessel.” Even worse, the ship was down to “five and a half Dutch butts of water,” which was at most a four-day supply. There was one other option. Cuba was just a day or two to the north. It was a Spanish territory, so landing there once again risked seizure of the vessel, but at least everyone would survive.

Robert Stubbs had brought the Zorg to the precipice of disaster. He chose not to stop in Tobago to replenish provisions. He failed to put the ship on short allowance once the water leakage had been discovered. He almost certainly botched the longitude reading. As a result, the Zorg was hundreds of miles off course with only a few days of water left. The only man who could have avoided these errors had been confined to quarters the entire time.

The final and most definitive evidence that James Kelsall was the ablest navigator aboard the Zorg, that he had been the primary man at the wheel since the ship departed the Cape Coast roads, and that he had not been consulted on the longitude reading, is that on November 29, 1781, Kelsall was “restored … to his former station of chief mate and he accordingly then took charge of the vessel again in that capacity.” During the fifteen days that Kelsall had been suspended from duty, everything that could possibly go wrong did. The decision by Collingwood to suspend him, and whatever influence Stubbs had on the decision, had been a monumental mistake. One can only imagine the conversation, in which a repentant Collingwood and Stubbs pleaded with Kelsall to save them.

Although James Kelsall was back on duty and able to steer the Zorg to its destination, the fact remained that the ship was ten days west of Jamaica with only four days of water left. A decision had to be made.

On the evening of November 29, 1781, the surviving crew of the Zorg gathered on the quarterdeck to discuss “how to act in that situation considering the small stock of water they had left.” A proposal was made, precisely by whom will never be known. This much, however, is for certain — following a discussion on the quarterdeck, “it was then determined by the general voice of the crew that part of the slaves should be destroyed to save the rest, and the remainder of the slaves and crew put on short allowance to save them from perishing.”

To save themselves, the crew of the Zorg chose murder.

Copyright ©2025 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group