Why was Pacific Northwest home to so many serial killers?

In ‘Murderland,’ alum explores lead-crime theory through lens of her own memories growing up there

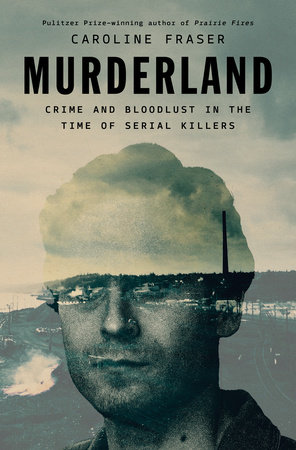

In Caroline Fraser’s 2025 book “Murderland,” the air is always thick with smog, and sinister beings lie around every corner.

Fraser, Ph.D. ’87, in her first book since “Prairie Fires,” her Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of “Little House on the Prairie” author Laura Ingalls Wilder, explores the proliferation of serial killers in the 1970s — weaving together ecological and social history, memoir, and disturbing scenes of predation and violence. The resulting narrative shifts the conventional focus on the psychology of serial killers to the environment around them. As the Pacific Northwest reels from a slew of serial murderers, Fraser turns toward the nearby smelters that shoot plumes of lead, arsenic, and cadmium into the air and the companies, government officials, and even citizens who are happy to overlook the pollution.

Of the Pacific Northwest’s most notorious killers, Fraser ties many to these smokestacks. Ted Bundy, whose crimes and background are discussed more than any other character, grew up in the shadows of the ASARCO copper smelter in Tacoma, Washington. Gary Ridgway grew up in Tacoma, too, and Charles Manson spent 10 years at a nearby prison, where lead has seeped into the soil. Richard Ramirez, known as the Night Stalker, grew up next to a different ASARCO smokestack in El Paso, Texas, long before committing murders in Los Angeles.

Fraser’s own experiences growing up in Mercer Island, Washington, add another eerie dimension. A classmate’s father blows up his home with the family inside. Another classmate becomes a serial killer. Her Christian Scientist father is menacing and abusive, and Fraser, as a child, considers ways to get rid of him, possibly by pushing him off a boat. The darkness is unrelenting; something is in the air.

To what extent environmental degradation directly led to the killings described in the book, Fraser leaves up to readers. “There are many things that probably contribute to somebody who commits these kinds of crimes,” she said in an interview. “I did not conceive of it as a work of criminology or an academic treatise on the lead-crime hypothesis. I really just wanted to tell a history about the history of the area — what I remember of it — and create a narrative that took all these things into account.”

“I did not conceive of it as a work of criminology or an academic treatise on the lead-crime hypothesis. I really just wanted to tell a history about the history of the area — what I remember of it — and create a narrative that took all these things into account.”

Fraser has been thinking about these ideas for decades. Before “Prairie Fires” was published, she had already written some of the memoir portions of the book, recalling the crimes and unusual occurrences near her family’s home. She was long interested in why there were so many serial killers in the Pacific Northwest and whether the answer was simply happenstance.

Though she had some knowledge of the pollution in Tacoma as a kid — the area’s smell was referred to as the “Aroma of Tacoma” due to sulfur emissions from a local factory — it wasn’t until decades later that she learned the full scope of industrial production and pollution.

Some revelations came by chance. When looking at one property on Vashon Island, across the Puget Sound from West Seattle, she came across a listing with the ominous warning — “arsenic remediation needed.”

“That just leapt out at me,” she said. “How can there be arsenic on Vashon Island?” After more research, she discovered that arsenic had come from the ASARCO smelter, on the south end of the same body of water. The damage reached much farther; the Washington State Department of Ecology says that air pollutants — mostly arsenic and lead — from the smelter settled on the surface soil of more than 1,000 square miles of the Puget Sound Basin.

“Much of Tacoma, with a population approaching 150,000, will record high lead levels in neighborhood soils,” Fraser wrote in the book, “but the Bundy family lives near a string of astonishingly high measurements of 280, 340, and 620 parts per million.”

The connection made Fraser focus more on the physical environment in which these serial killers lived and less on other factors — like a history of abuse — on which true-crime writers have historically placed greater emphasis.

In this ecological pursuit, Fraser points readers toward once-ubiquitous sources of pollution like leaded gas and the industry forces that popularized them against advice from public-health experts.

American physicians raise concerns that lead particulates will blanket the nation’s roads and highways, poisoning neighborhoods slowly and “insidiously.” They call it “the greatest single question in the field of public health that has ever faced the American public.” Their concerns are swept aside, however, and Frank Howard, a vice president of the Ethyl Corporation, a joint venture between General Motors and Standard Oil, calls leaded gasoline a “gift of God.”

Though Fraser doesn’t explicitly support the lead-crime hypothesis, the core of the idea — that greater exposure to lead results in higher rates of crime — remains central. In the book’s final chapter, Fraser cites the work of economist Jessica Wolpaw Reyes, Ph.D. ’02, who concluded in her dissertation that lead exposure correlates with higher adult crime rates.

Regardless of exactly how much this hypothesis can be assuredly proven, Fraser thinks the connections between unapologetic and unfettered pollution and violent crime warrant scrutiny. In “Murderland,” she gives the idea, and an era of crime, a nimble, haunting narrative.