How market reactions to recent U.S. tariffs hint at start of global shift for nation

Economist updates literature on optimal American import-tax rate in world of interconnected trade, investment

President Trump’s tariffs, announced on April 2, upset the global economy in new ways.

“The financial meltdown they triggered was really striking,” said Oleg Itskhoki, a professor of economics. “What happened to the stock market, what happened to bond yields, what happened to the dollar exchange rate. They’re all connected. You can’t study tariffs anymore without considering what happens in the financial market.”

In a new working paper, Itskhoki and longtime collaborator Dmitry Mukhin of the London School of Economics explore what they call “the optimal macro tariff,” or the import tax rate most favorable to U.S. economic interests. The international macroeconomists are known for their work detailing how today’s globalized financial market drives currency valuations. Now they’ve expanded that approach to study tariffs for a variety of U.S. policy objectives.

The academic literature was due for an update. The last time the world saw tariffs on this scale was the 1930s, when countries including the U.S. sought to protect jobs amid the Great Depression’s high unemployment.

“There was no wave of protectionism after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and ’09, when unemployment in the U.S. exceeded 10 percent,” Itskhoki noted. “It seemed like the developed world had shifted to an equilibrium without tariffs.”

We sat down with Itskhoki recently to ask how tariffs function in a world of deeply interconnected trade and investment. The conversation was edited for length and clarity.

What, exactly, is an “optimal macro tariff”?

The economic literature on optimal tariffs typically asks, “What policy gives a country the most favorable terms of trade with the rest of the world?” That literature typically assumes trade balance, but the last time the U.S. had anything close to balanced trade was 1991 or ’92.

At the same time, macroeconomists tend to think about trade imbalances without considering tariffs too much. What we do in this paper is combine the two.

You’ve bridged two very different traditions within economics.

Yes. Because we’ve seen not only the globalization of trade, we’ve also seen the globalization of financial markets with countries holding large portfolios of foreign assets. As it turns out, this is consequential for the optimal tariff.

Your paper focuses on optimal macro tariffs for the U.S. What should we know about the country’s place in the global economy at this very moment?

Macroeconomic research over the last 20 years focused on what is sometimes called the “exorbitant privilege” of the United States.

The country may have had a persistent trade deficit and consequently accumulated fewer assets than liabilities. But its foreign assets tended to be of the riskier sort, like direct foreign investments and portfolio holdings. They generated high returns relative to liabilities — which are, to a large extent, U.S. Treasuries.

And the federal government enjoyed paying low returns on U.S. Treasuries until recently because they were viewed as the world’s safest asset. That’s what allowed the U.S. to run a trade deficit and the U.S. government to run a large fiscal deficit without dire financial consequences.

Higher interest rates mean that required yields on U.S. Treasuries are now quite high, so the government can no longer borrow cheaply. Interest rate payments on federal debt are now around half the country’s massive fiscal deficit, by itself larger than the trade deficit.

We typically see developing countries going into periods of big trade deficits and big fiscal deficits. It’s very unusual to find the world’s dominant country in this position.

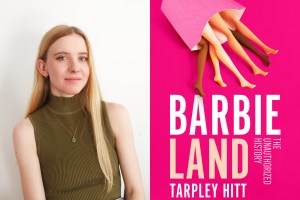

Oleg Itskhoki.

Veasey Conway/Harvard Staff Photographer

What happens when you add tariffs to the mix?

The dollar appreciated, in line with theoretical predictions, with most previous tariff announcements. With tariffs, Americans buy fewer imports. Less foreign exchange is needed to pay for them, so there are more dollars left over, and the currency becomes stronger. That, in turn, hurts U.S. exporters, because American goods became more expensive overseas. Hence, foreigners buy less, resulting in a new equilibrium with less trade on both sides.

In addition, dollar appreciations are akin to a financial transfer from the U.S. to the parts of the world that hold U.S. assets — the so-called “valuation effects.”

Therefore, in a financially globalized world, the optimal tariff for the U.S. is smaller than in previous eras. Furthermore, holdings of U.S. assets offer an effective insurance for countries like China and Japan against a possible trade war with the U.S.

But that’s not what played out after April 2. Instead, we saw a depreciating U.S. dollar. Why?

This was surprising indeed. Dollar depreciation happened along with a large meltdown in the U.S. stock market and increasing yields on U.S. Treasuries. At first there was a theory that foreigners were dumping Treasuries. But in reality, there was not much else for them to buy. Maybe they wanted to sell U.S. Treasuries and buy, say, German Bunds of equal quality. In reality, there are 10 times fewer German bunds than U.S. Treasuries out there today, making it difficult to shift portfolios away from the U.S. assets.

Instead what we saw was a clear turn in the currency market. In the past, Asian investors in particular but also European investors to some extent were willing to buy U.S. Treasuries without holding currency insurance. The market expected the U.S. dollar to always appreciate in bad economic times. But April 2 was the first time the dollar massively depreciated in bad times, as global markets turned to pessimism on the announcement of the trade war.

The U.S. dollar now resembles the British pound following the 2016 Brexit vote. Before April 2, Japanese pension funds, for example, may have been willing to hold U.S. assets without buying currency insurance. Now they want to sell that risk of U.S. dollar depreciation to the market. And the required premium for selling that risk resulted in a weaker dollar.

Has the U.S. benefited at all from the trade war?

Well, the U.S. is collecting tariff revenues. But for these very immediate, and very small, monetary gains, the government has potentially triggered a much bigger process that will eliminate some of the benefits the country has enjoyed. I mean, you can call French President Emmanuel Macron or U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer to negotiate on tariffs. But you cannot call up the financial market and tell it to have faith in the dollar.

“It doesn’t mean the U.S. will immediately lose its central place in the global financial market, but it is clear that the tariffs marked the start of some sort of realignment.”

It doesn’t mean the U.S. will immediately lose its central place in the global financial market, but it is clear that the tariffs marked the start of some sort of realignment. The fact that we’re discussing a tax bill that is meant to increase the deficit, in this environment, is just insane.

What should laypeople know about the model you’ve constructed to study optimal macro tariffs?

The model provides a formalized environment where you can ask questions and get coherent answers. You can play around with different objectives, like raising revenue or boosting manufacturing employment. We found that indeed there is an optimal tariff for the U.S. — somewhere between 25 and 35 percent — if one ignores the financial market.

But even then, it only works if the government convinces the rest of the world not to retaliate, because there’s a much bigger loss if everybody starts doing tariffs. That’s pretty much how the world lived before the Second World War, before all that collective effort was done to bring down tariffs.

Suddenly, the very myopic optimal tariff has won the day once more. Once we factor in the financial market, the optimal tariff is actually much smaller, at something like 9 percent. And this only takes into account the direct financial losses from valuation effects, without capturing the consequences of the U.S. losing its dominance in the global financial market.

You mentioned playing around with different policy objectives. According to your model, what is the optimal tariff for boosting employment in U.S. manufacturing?

We really thought there would be an optimal tariff for manufacturing employment. It shows you how biased we are. Because make no mistake, tariffs are a trade tax. They reduce the size of the tradable sector, meaning they reduce both imports and exports. It’s true that increased trade with China hurt U.S. manufacturing. But today, a tariff on trade with China will hurt U.S. manufacturing even further.

If the goal is boosting tradable employment, what you actually want are subsidies. Maybe particular regions are targeted. Maybe we decide that certain industries are important — for security, for defense, for maintaining our technological leadership. Ideally, U.S. society would need to decide through the democratic process what activities to subsidize within a balanced budget, given the high costs of borrowing right now. But we are obviously very far from this ideal.