From ‘joyous’ to ‘erotically engaged’ to ‘white-hot angry’

Stephanie Burt’s new anthology rounds up 51 works by queer and trans poets spanning generations

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

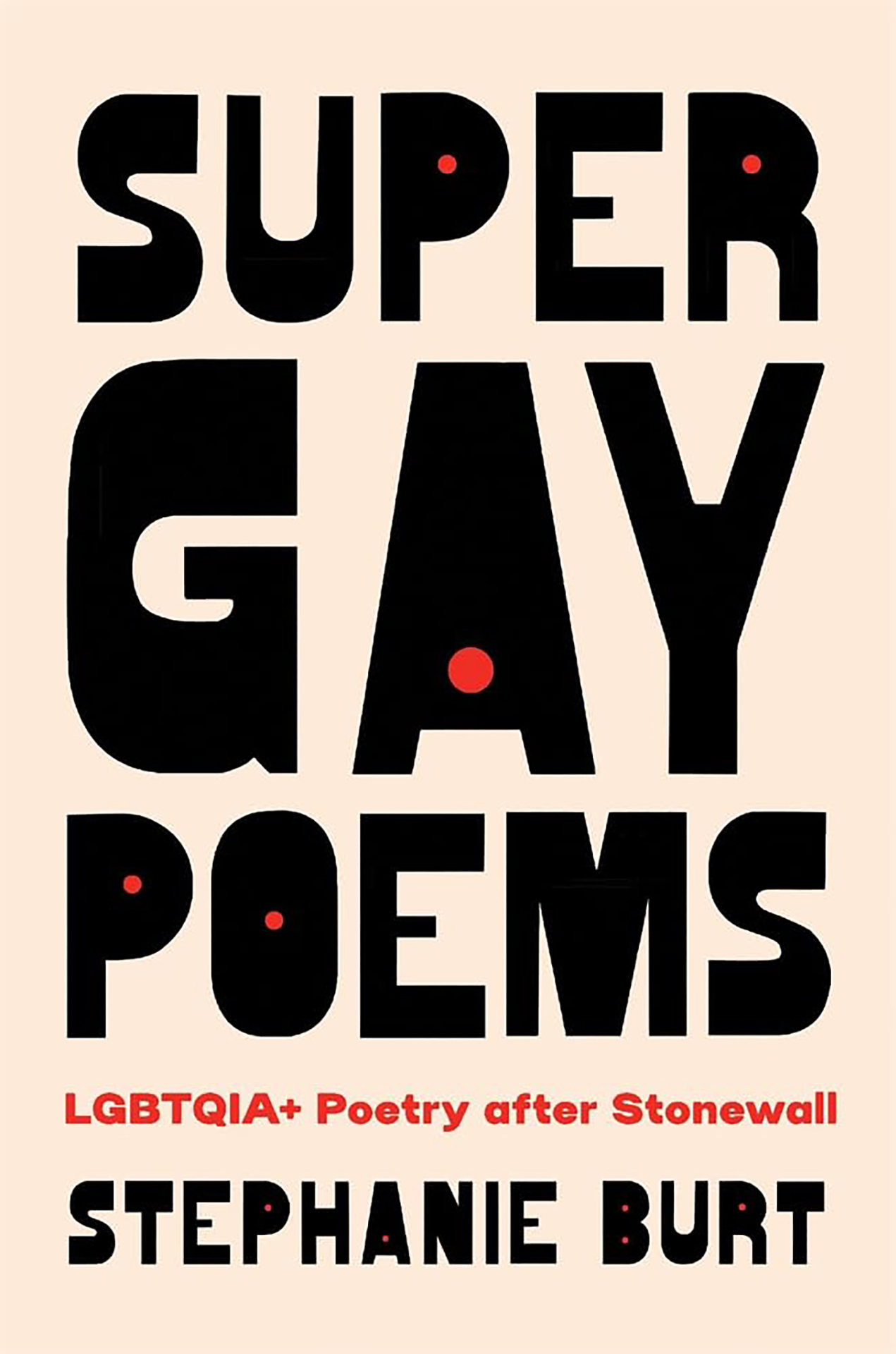

As Stephanie Burt sees it, queer lyric poetry mirrors the patterns of queer life. She offers many examples in “Super Gay Poems: LGBTQIA+ Poetry After Stonewall,” a new anthology of 51 works by queer and trans poets from the last 55 years.

“I chose only poems I admire and wanted to write an essay about,” said Burt, Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor of English, who paired each work with an original essay providing analysis and historical context. “I looked for stylistic range, from concise to effusive, rhymed-formal to free and chaotic, weird-and-challenging to apparently pellucid. I also looked for emotional range, from joyous to erotically engaged to white-hot angry, quietly curious, resolved, mournful, inviting, shy, and extroverted.”

Burt’s chosen poets span generations, from Frank O’Hara (1926-1966) to Logan February (born in 1999), and address major moments in modern queer history — from Paul Monette’s “The Worrying” (1988) responding to the HIV/AIDS crisis, to Jackie Kay’s “Mummy and donor and Deirdre” (1991), which explores the increasing visibility of queer families.

The anthology also reflects a wide geographic range, from Puerto Rican writer Roque Salas Rivera to Singaporean writer Stephanie Chan. Some names, like Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich, will be familiar to many readers, while others may offer new discoveries.

In this edited conversation with the Gazette, Burt discusses shifts in the poetry landscape, the thrill of discovering new voices, and the power of poetry to capture historic moments.

Could you talk more about the notion of time in LGBTQIA+ poetry?

Many of us grew up with a very clear, normative set of expectations about how life works: You’re a child, then a teen, and then an adult, and then you’re old. You hang out in same-sex friend groups, and then you date, and then you “get serious,” and then you get married and have kids and raise kids, ideally 2.6 of them.

Often queer time, as encapsulated and addressed in queer poems, works differently. You don’t “grow up” if growing up means abandoning your intimate same-sex attachments in favor of straight-passing dating. Or you, as an adult, derive your energy from the kinds of exciting parties adults are supposed to abandon. Or maybe you go through puberty twice and feel (or act) like a baffled, excitable teen when you’re an adult. Even if you do end up monogamously connected to one stable partner for decades, as several of my poets did, the poetry about that connection works differently: It can feel more hard-won or feel like a former secret.

What changes do we see in LGBTQIA+ poetry after the 1969 Stonewall Uprising?

Post-Stonewall, we see more people come out. More people celebrate, openly, long-term relationships. People raise kids and attend to a next generation. During the 1970s, lesbian poets celebrate lesbian-only or women-only spaces; later on, not so much. During the 1980s and early 1990s, a whole generation — especially, but not only, gay men — lose half or more of their friends to HIV/AIDS, which is still a killer in much of the world but shows up less often in poems.

During the 2010s, people come out as trans or nonbinary. Also during the 2000s and 2010s, more people in the Global South come out and write poems about how their multiple identities and forms of belonging intersect. Sometimes they feel welcome where they grew up, and sometimes — as is the case with Logan February, whose poem “Prayer of the Slut” (2020) is included in the book — they do not and cannot.

Did you make any new discoveries while compiling this book?

Yes, I had never encountered Cherry Smyth, whose poem “In the South That Winter” (2001) is included, or Logan February. I hadn’t paid enough close attention to Melvin Dixon (“The Falling Sky,” written 1992, published 1995), nor to Judy Grahn (“Carol, in the park, chewing on straws,” 1970) until this book gave me the chance to re-examine their work.

Do you see poetry as a tool for documenting LGBTQIA+ history?

All art forms document history because all works of art come from historic moments. I picked the poems here because I loved them all, but some parts of global queer history in English don’t show up because I didn’t or couldn’t find awesome poems about them: queer liberation in the Republic of Ireland, for example, or the relationship between the Filipino diaspora and Filipino/a/x bakla identities. For that latter I recommend Rob Macaisa Colgate’s amazeballs book, published after “Super Gay Poems” went to press.

I did happily — but also sadly — include poems tied to big-deal historic moments such as Paul Monette’s AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power verse [“The Worrying”] which really needs another look these days. That said, some of my favorite poems have nothing to do with big chapters in public history — they construct aesthetic refuges from it, or alternatives to it. May Swenson’s “Found in Diary Dated May 29, 1973” (first book publication 2003), for example, an allegory of lesbian love via plant roots. You can connect it to history if you like, but that’s not what the poem invites us to do first or last.

What do you hope readers will take away from this anthology?

New favorite poets! New favorite poems! And a sense of the queer and trans and ace and intersex and pan and so on possibilities out there today, even at this troubled time for so many of us — possibilities that include fears and catastrophes but also resilience, community, solidarity, and joy.