From bad to worse

Photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Harvard faculty recommend bios of infamous historical figures

Writing biographies of bad people is challenging, said Harvard historian Fredrik Logevall. “Somehow monsters must be made to be human and complex if we are to understand why they behaved as they did.” To that end, we asked Logevall and other Harvard faculty members to recommend books about controversial historical figures that help us better understand humanity’s worst impulses.

‘James Henry Hammond and the Old South’

by Drew Gilpin Faust

Jonathan Hansen

Senior Lecturer on Social Studies

James Henry Hammond — who served as the governor of South Carolina from 1842 to 1844 and as a U.S. senator from 1857 to 1860 — was, Hansen said, “arguably one of the most articulate apologists for slavery in American history and a real shit.”

“He was born very poor and did something that virtually nobody was able to do at the time, namely, he married out of his class to a wealthy Southern belle, becoming immediately rich. He was an absolute polymath, as bright and talented as Jefferson, as interested (and accomplished) in agronomy, say, as he was in economics and politics.

“The tragedy here, as so often in American history, is that he took the racial rather than the class route (think Edmund Morgan, ‘American Slavery, American Freedom’); had he combined with other poor folk in his neighborhood (state, region, nation), there is no telling what he might have done. In Faust’s telling, his godawful life is a not-unfamiliar American tragedy. Hers is a pellucid, sympathetic recreation of a brilliant, pathetic, ultimately dejected man.

“It’s a triumph of what I like to think of as history as an exercise in moral imagination. In Faust’s hands, Hammond’s life becomes a tragedy, what coulda, shoulda, mighta been if Hammond’s path had gone another direction.”

‘Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man’

by Garry Wills

Joyce Chaplin

James Duncan Phillips Professor of Early American History

“He is ‘President of the forgotten men,’ figurehead of ‘affluent displaced persons who howled at … rallies, heartbroken, moneyed, without style,’ self-described ‘rugged individuals,’ linked in ‘compulsory technological interdependence.’ Thus Garry Wills skewers a man (and his supporters) in his biography of a bona fide bad person: Richard Milhous Nixon,” Chaplin said.

“Before Watergate, ‘Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man’ (1969) prophesied the 37th president’s dark potential. Nixon was the last true liberal, Wills argues. But, by the 1960s, classical liberalism lacked moral authority. Nixon’s endless self-praise as a self-made man charmed few. Having wealth and position with no effort was back in style, and radical protest against power and privilege was ascending — two decidedly non-liberal positions were colliding. Indifference to Nixon’s upward mobility — or, worse, mockery of it — ‘would gall him and breed resentment.’ Was Watergate the apotheosis? Only for Nixon. The aggrieved ‘rugged individuals’ in ‘compulsory technological interdependence’ are still with us.”

‘G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century’

by Beverly Gage

Ariane Liazos

Lecturer, Harvard Extension School

Liazos often assigns books about complicated or terrible people in her course on writing biographies to help students understand that their job is not to “celebrate heroes or condemn villains” but rather “to craft nuanced accounts that help us better understand complicated individuals and the worlds they inhabited.” Beverly Gage’s biography of J. Edgar Hoover, she said, does just that.

“Today, Hoover is infamous for his abuses of power as director of the FBI for 48 years. He instigated unprecedented levels of government surveillance and repression. He orchestrated illegal wiretaps, spread false rumors, and even planted evidence to suppress groups he deemed subversive, aggressively targeting alleged communists and Civil Rights activists in particular. While he professed to be a nonpartisan law-enforcement administrator, he used the FBI to support those who shared his own political views.

“Gage certainly does not hesitate to document his many abuses of power, but she also strives to make sure her readers see Hoover as ‘more than a one-dimensional tyrant and backroom schemer.’ As she writes, ‘This book is less about judging him and more about understanding him.’ She does this, as all good biographers do, by helping her readers see his humanity, beginning with a compelling account of his deeply troubled childhood. She presents a portrait of a highly intelligent, ambitious, ruthless, flawed, and deeply contradictory man.

“Yet the additional and crucial message that Gage so expertly conveys is that, despite his reputation today, Hoover was extremely popular not only with political elites but with much of the American public. In doing so, she forces us to avoid demonizing one individual and instead look more honesty at our shared history. As she notes, ‘To look at him is also to look at ourselves, at what America valued and fought over during those years, what we tolerated and what we refused to see.’”

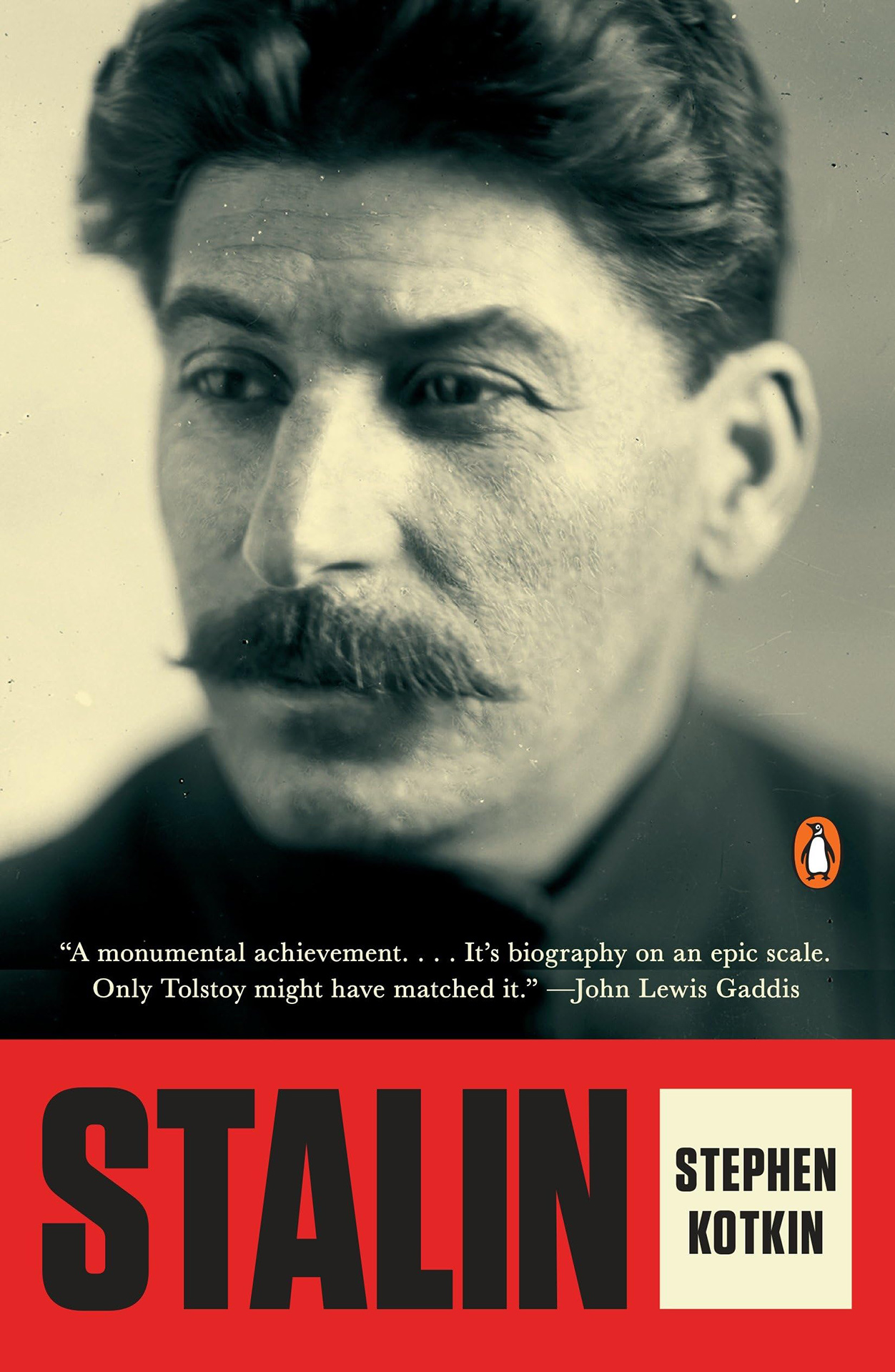

‘Stalin’

by Stephen Kotkin

Fredrik Logevall

Laurence D. Belfer Professor of International Affairs, Professor of History

“It’s challenging to write in-depth studies of terrible people,” Logevall said. “Somehow monsters must be made to be human and complex if we are to understand why they behaved as they did. One work that succeeds marvelously in this regard is Stephen Kotkin’s ‘Stalin,’ a multi-volume biography of the Soviet dictator.

“This is biography on a grand scale, a textured, analytically nuanced narrative drawing on immense research in a wide array of sources. It is, moreover, a true ‘life and times’ study, in which Kotkin uses his skills as historian to contextualize Stalin’s life, situating him within the broader environment in which he rose to power. In so doing, Kotkin adroitly balances the roles played by individual agency on the one hand, with deeper, structural forces on the other, while also revealing much about those with whom Stalin shared the stage, not least Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky. The two volumes bring out what the third will also surely show, and what more recent history amply demonstrates: that if circumstances make the leader, the reverse can be no less true.”

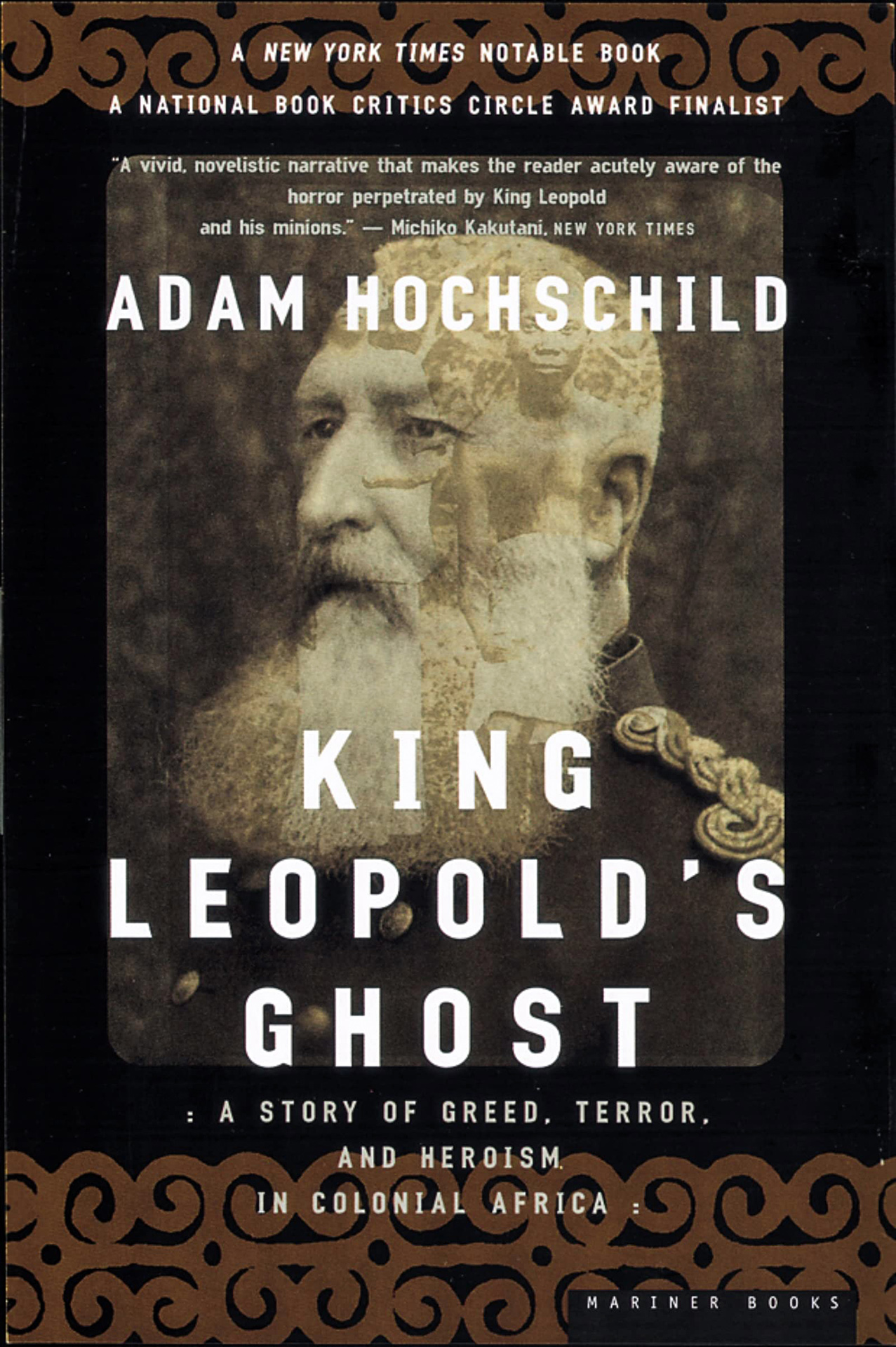

‘King Leopold’s Ghost’

by Adam Hochschild

Louisa Thomas

Visiting Lecturer on English

“There are villains, and then there is King Leopold II, the man at the center of Adam Hochschild’s brilliant and disturbing account of the Belgian who seized the territory surrounding the Congo River, plundered it, and destroyed its people,” said Thomas. “‘King Leopold’s Ghost’ not only brought to light the long-overlooked crimes of the despot, but it also tells stories of people who suffered from them and of those who resisted them. That project is now, and always, necessary, if we are to remain aware of the moral dimension of human affairs.”