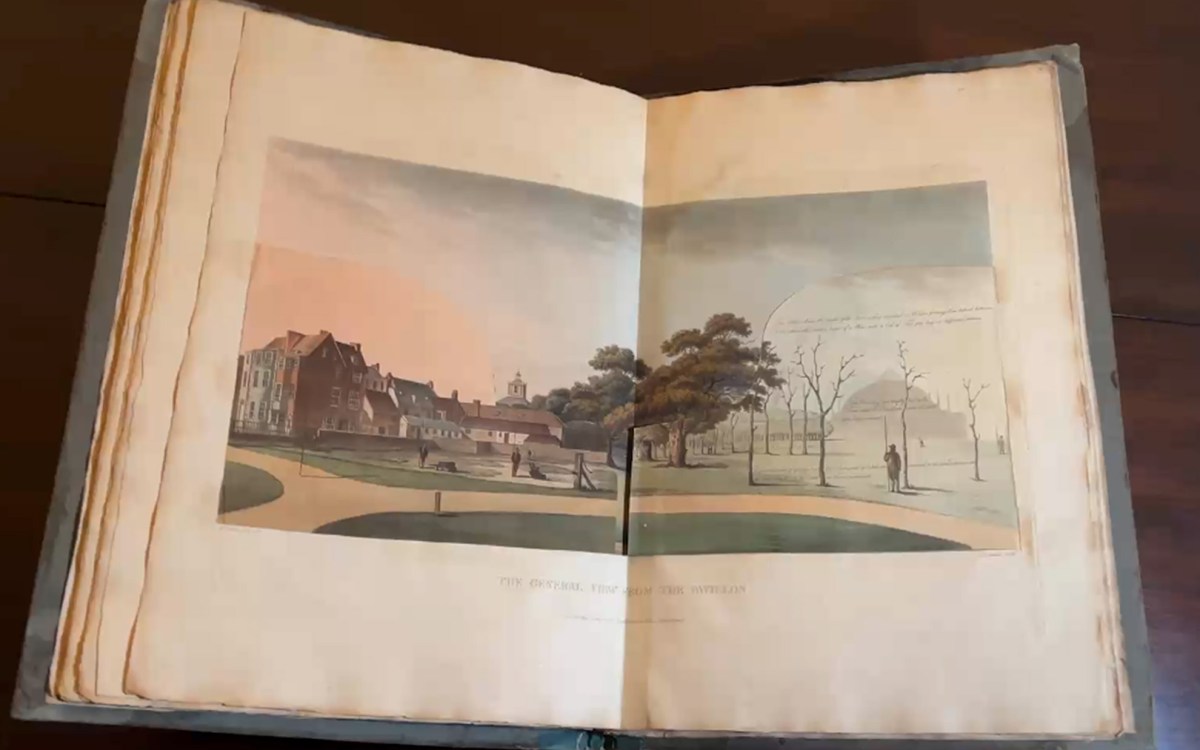

Krista River and the Arneis Quartet.

Photos by Dylan Goodman

Talking about music doesn’t have to be difficult

Yeats poem inspires 3 songs and deep listening, discussion at Mahindra event

Music can be difficult to talk about. But WordSong, which styles itself “Boston’s premier interactive concert organization,” confronts the fraught relationship between music and words directly.

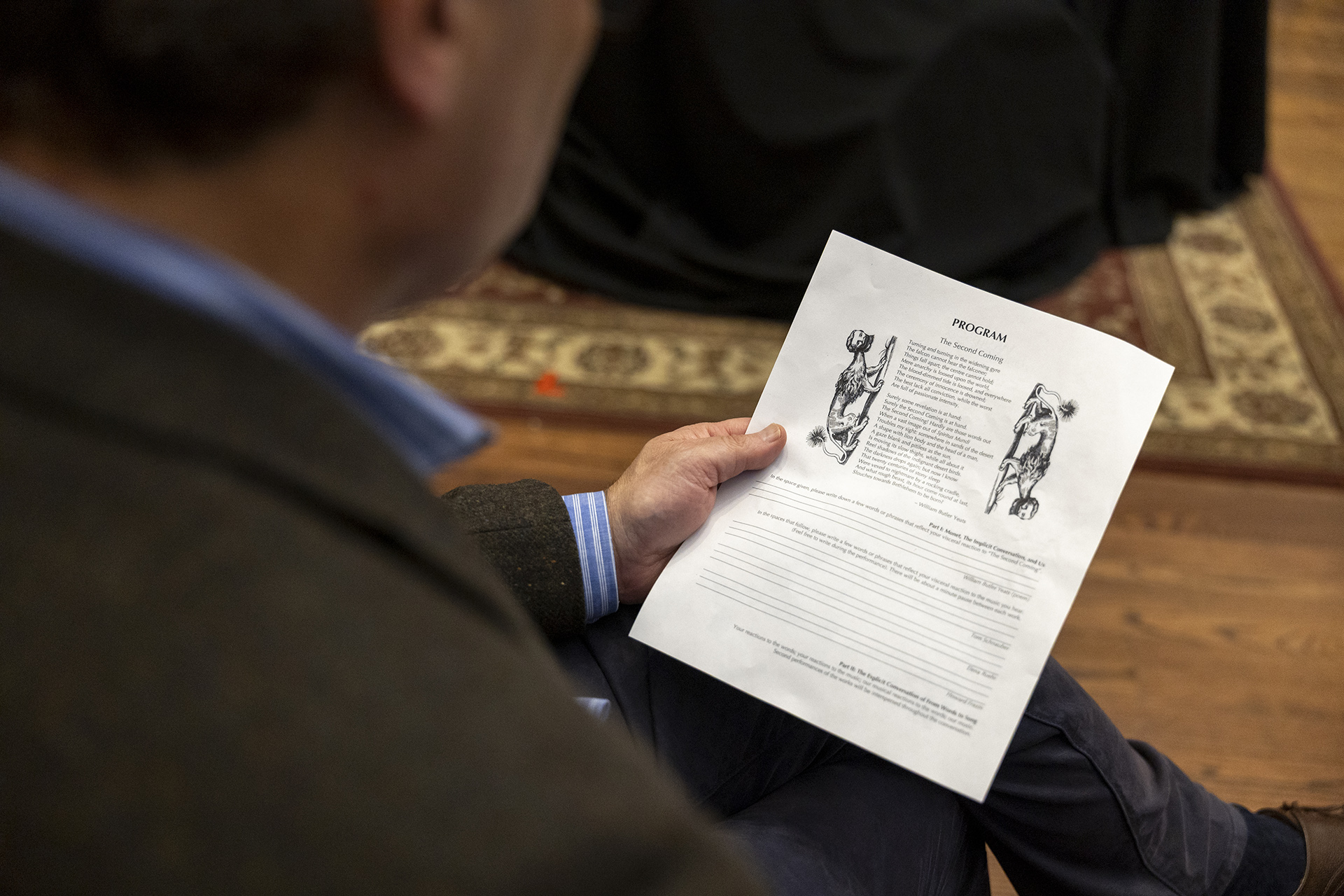

Earlier this month the Mahindra Humanities Center hosted a WordSong performance and discussion centered on William Butler Yeats’ “The Second Coming.” By commissioning multiple composers to set a single text to music and then inviting discussion about the poem and its varied musical settings, the series invites deeper listening of both poetry and contemporary composition.

The occasion, co-sponsored by Arts and Humanities Dean Sean Kelly, marked the premiere of short pieces by Boston-area composers Elena Ruehr, Howard Frazin, and Tom Schnauber. All three works were performed in Holden Chapel by the local Grammy Award-winning mezzo-soprano Krista River and New England-based Arneis Quartet.

“It’s difficult to talk about music, but we believe that everybody can,” said Schnauber, who founded WordSong with Frazin in 2008.

However, the German American composer added: “It is easier to talk about words than about music.”

With that in mind, the program began with a reading of Yeats’ poem. Its imagery of disconnection and a strange Sphynx-like creature waking as a moment of doom approaches, was written in 1919. That tumultuous time, following the horrific destruction of the first World War as well as Ireland’s struggles for independence, echoes into our own era, as audience members quickly noted.

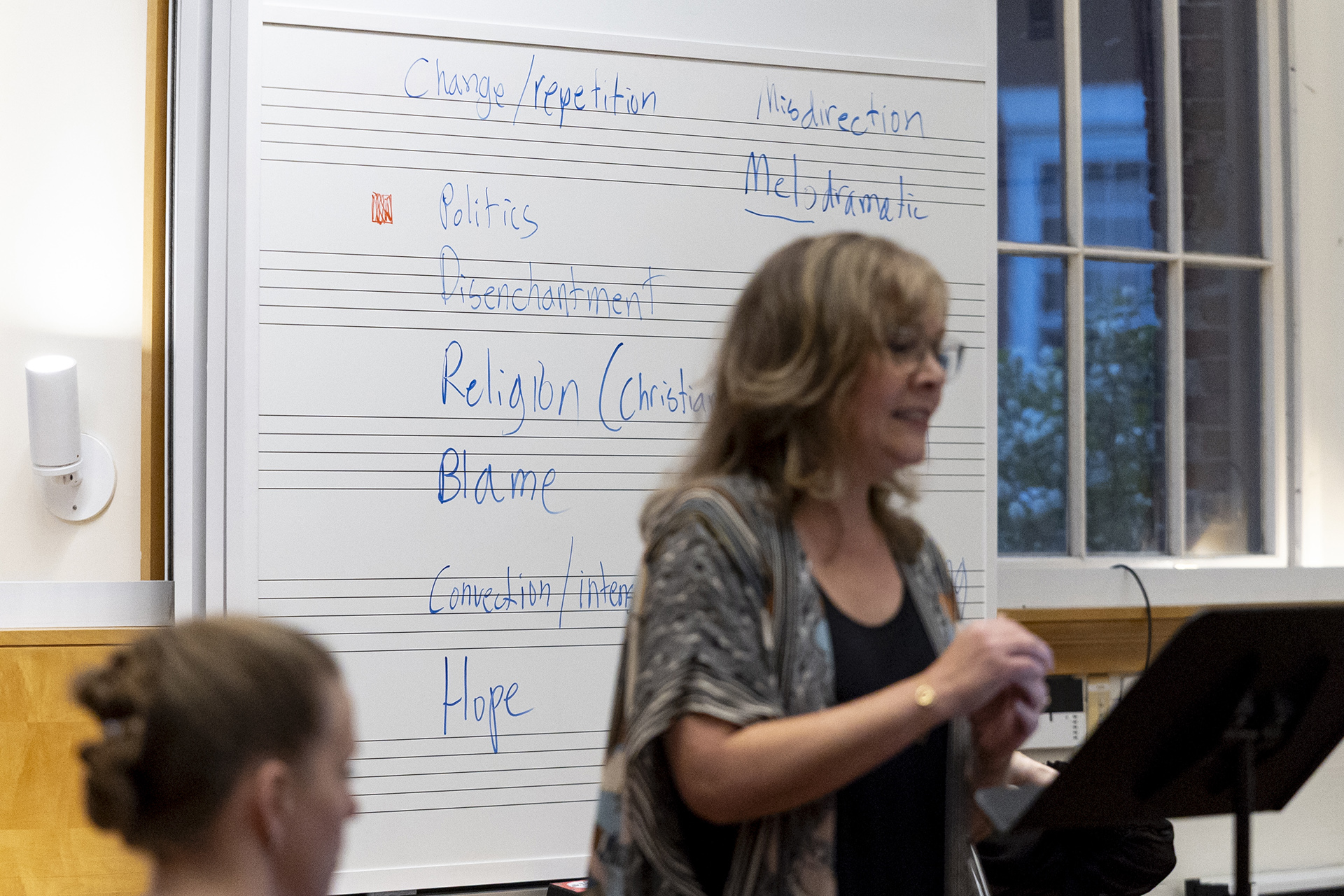

As attendees chimed in about what the poem evoked for them, Schnauber jotted down themes on a white board. They included politics, disenchantment, and blame as well as religion and Einstein, whose theory of relativity was relatively new when the poem was written. Also brought up was Yeats’ animal imagery (“the falcon cannot hear the falconer”) and the poem’s structure, including its use of repetition.

The three compositions took different approaches to the text.

Schnauber’s setting was performed first. A cappella sections, which left River’s voice exposed, were used to accentuate phrases, as when the soprano mused over the title line. Pizzicato passages played up the disconnection that is a theme of the poem.

Ruehr’s composition took a more lyrical approach. Perhaps in response to the circling falcon of the first stanza, repeated (or circling) motifs gave way to the disruption of harsh staccato passages. The music of the string quartet then turned almost dreamy for the poem’s contemplative second stanza.

Frazin’s piece started with River singing a cappella before a dramatic entrance by the strings, the instrumentals accenting the long, held vocal phrasings. This piece also made use of a few repeated motifs passed between the viola and the cello, the instrument most associated with the human voice.

After the three pieces were performed, the composers invited audience comments. Attendees remarked how different musical settings played up various emotional responses.

At times, the conversation focused on what imagery each musical piece highlighted. When Ruehr noted that the natural imagery was important to her, a listener said that had been clear in the music: “I heard the falcon swooping in yours.”

During the conversation, each piece was performed for a second time, provoking more conversation about what each composer sought to emphasize, and which were the most successful. Comments ranged from technical critiques, with some listeners saying they heard echoes of early religious or Irish folk music in the compositions, to emotional reactions.

When Schnauber and Frazin got to the monstrous “rough beast” of the second stanza, one listener noted, the effect was “cataclysmic.” In Frazin’s piece, that listener said, the effect was more “resigned.”

As the conversation turned once again to the events of Yeats’ time, Frazin emphasized how relevant the poem, and the pieces it inspired, are today.

“We’re living through a time not so unlike his time, and there are very complicated emotional conflicts,” said the composer, who also serves as WordSong’s artistic director. This raises its own questions. “Even if you don’t like something, what you are going to do about it is complicated. We are having to step back and say, how did we get here?”

As the conversation continued well past the event’s scheduled end time, it was clear that neither the text nor the music had left the audience at a loss for words.

“Listeners know a lot more than they think they do,” said Frazin. He credited people’s “intuitive artistic understanding,” an understanding that is aided by the sharing of ideas.