Maria and Julia Lisella (from left), Josh Kurtz, and Kenny Likis collaborate and reflect on their writing during a workshop in Harvard’s Woodberry Poetry Room.

Photos by Grace DuVal

Making universal connection through the intensely personal

Woodberry Poetry Room workshop project on tradition of elegy inspired by loneliness, grief of pandemic

Elegy, a form of poetry traditionally meant to honor the dead and lament the loss, is often composed in solitude. On a warm recent Tuesday afternoon in Lamont Library, a small group — some poets, most not — gathered to write, read, and workshop elegies of their own.

The workshop, led by Karen Elizabeth Bishop and David Sherman in partnership with the Woodberry Poetry Room, is part of the duo’s ongoing “Elegy Project.” The event late last month was paired with a reading that evening in Houghton Library’s Edison Newman Room by poet Peter Gizzi, author of the T.S. Eliot Prize-winning collection “Fierce Elegy.”

“The Elegy Project is a public poetry initiative,” Sherman said. “We put poem cards in public places for strangers … Our intention is to make grief less lonely.”

The Elegy Project was the recipient of the Poetry Room’s 2023 Community Megaphone grant. Using funds provided by poet Tom Healy ’83, the Poetry Room began offering stipends to individuals and nonprofits in the Boston area to support their work and creative contributions to the community.

“Elegy is perhaps the most primal and human of poetic impulses — the need to mourn, to praise, and to console all springing from the inescapable human predicament: to be alive is to experience loss,” said Mary Walker Graham, associate curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room. “Elegy not only makes this loss more bearable, it enlarges our capacity to experience the full spectrum of human emotion.”

Started in spring of 2022, Bishop and Sherman said they were inspired to create the Elegy Project when they noticed the loneliness and grief caused by the pandemic and thought there must be a way to show people that they weren’t alone.

“During the pandemic we wanted to do an anthology of elegy. But the publishing world works at glacial speed,” Bishop said. “Everybody was in their houses. And so we thought to do a deconstructed anthology that would be immediately free and accessible, and ‘aggressively randomly accessible,’ as Dave says.”

Both Bishop and Sherman distribute poetry cards wherever they go.

“I walk around with thumbtacks in my pocket and the cards, and I put them on wooden utility poles, or leave them in the post office, on the train, or the bus, or maybe a bench, and it’s aggressively contingent and random,” Sherman said. “It’s unsystematic. It’s aggressively embracing randomness.”

Both Bishop and Sherman say they use elegy in their professional work as well. Bishop is an associate professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature at Rutgers University, where she researches and teaches modern poetry and narrative. Sherman is an associate professor of English at Brandeis University, where he researches elegy and the politics of commemoration.

“I think that elegy performs this beautiful kind of stretching toward something that’s gone or something that’s gone missing,” Bishop said. “Isn’t that the nature of death? That you want to reach out, you want to kind of make that movement forward.”

Kenny Likis (center) and other participants use the Poetry Room’s collection and prompts by workshop leaders for inspiration.

Xiaolong Yang (left), a student at the Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, compares notes with poet Hajjar Baban.

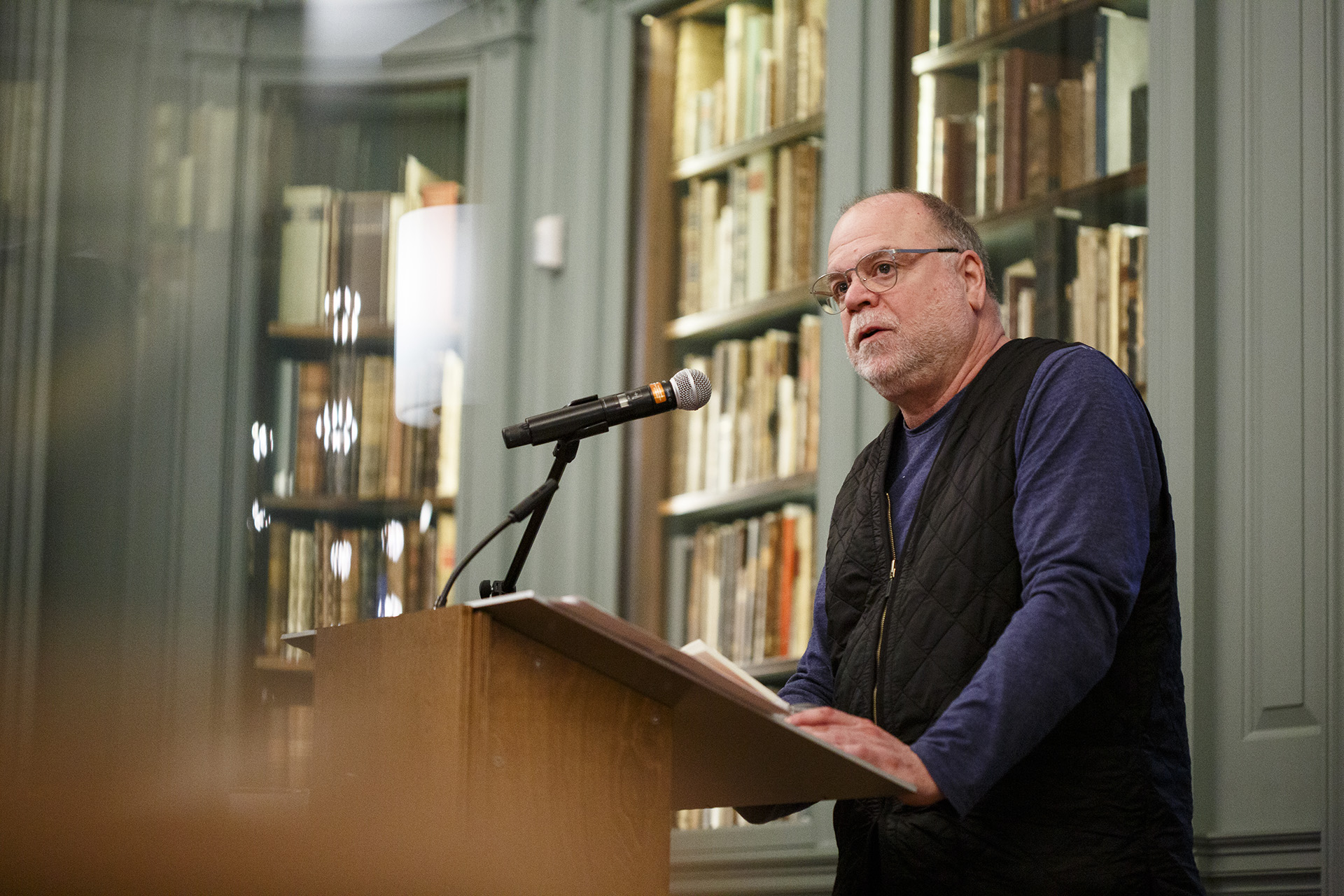

“Our intention is to make grief less lonely,” said Elegy Project co-founder David Sherman (right).

This most recent workshop was the second between the Elegy Project and the Poetry Room. Last spring they did poetry workshops with invited guests. This time around, there was an open call for anyone interested in crafting a poem.

“I think these are people who probably use poetry privately and maybe share with a few friends, and want to expand that experience by a significant step,” Sherman said. “These were people who are busy with life, busy with real experiences where poetry is useful for processing, and they just want to write in community.”

The group assembled ranged from doctoral candidates in physics to retired painters. They were asked to use the Poetry Room’s collection and prompts by Sherman and Bishop for inspiration.

“Elegy is perhaps the most primal and human of poetic impulses — the need to mourn, to praise, and to console all springing from the inescapable human predicament: to be alive is to experience loss.”

Mary Walker Graham

“The thought behind the steps was to create a dynamic conversation between people and books, between people and people, between lines and other lines, so that something unexpected would emerge,” Sherman said. “It was exploring openly, exploring new books on the shelves, and then feeling the desire to say something back of your own.”

Bishop added that using prompts and exploring texts can help get the creative juices flowing, too.

“It takes a little bit of the pressure off sitting around waiting for a line to appear or waiting for your brain to come up with something,” she said. “I think that that kind of scaffolding is really useful for people to get into to writing a poem or just engage poetry in some way.”

Graham, the Poetry Room’s associate curator and co-organizer of the event, said workshops like the Elegy Project’s are important to engage the community and bring poetry out from the stacks.

“Poetry belongs to everyone, not just to the authors of published books,” she said. “We all have an equal right to access it, not only to receive it but to create it. Workshops like this one nurture the poets in us all.”