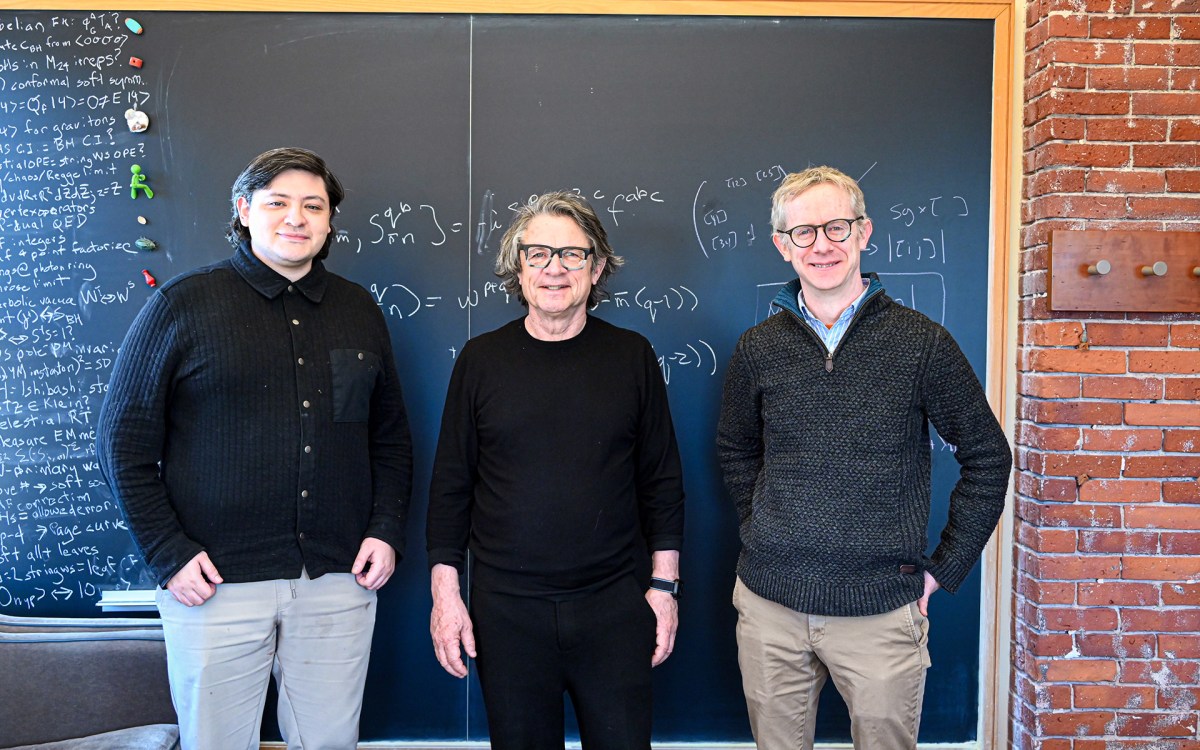

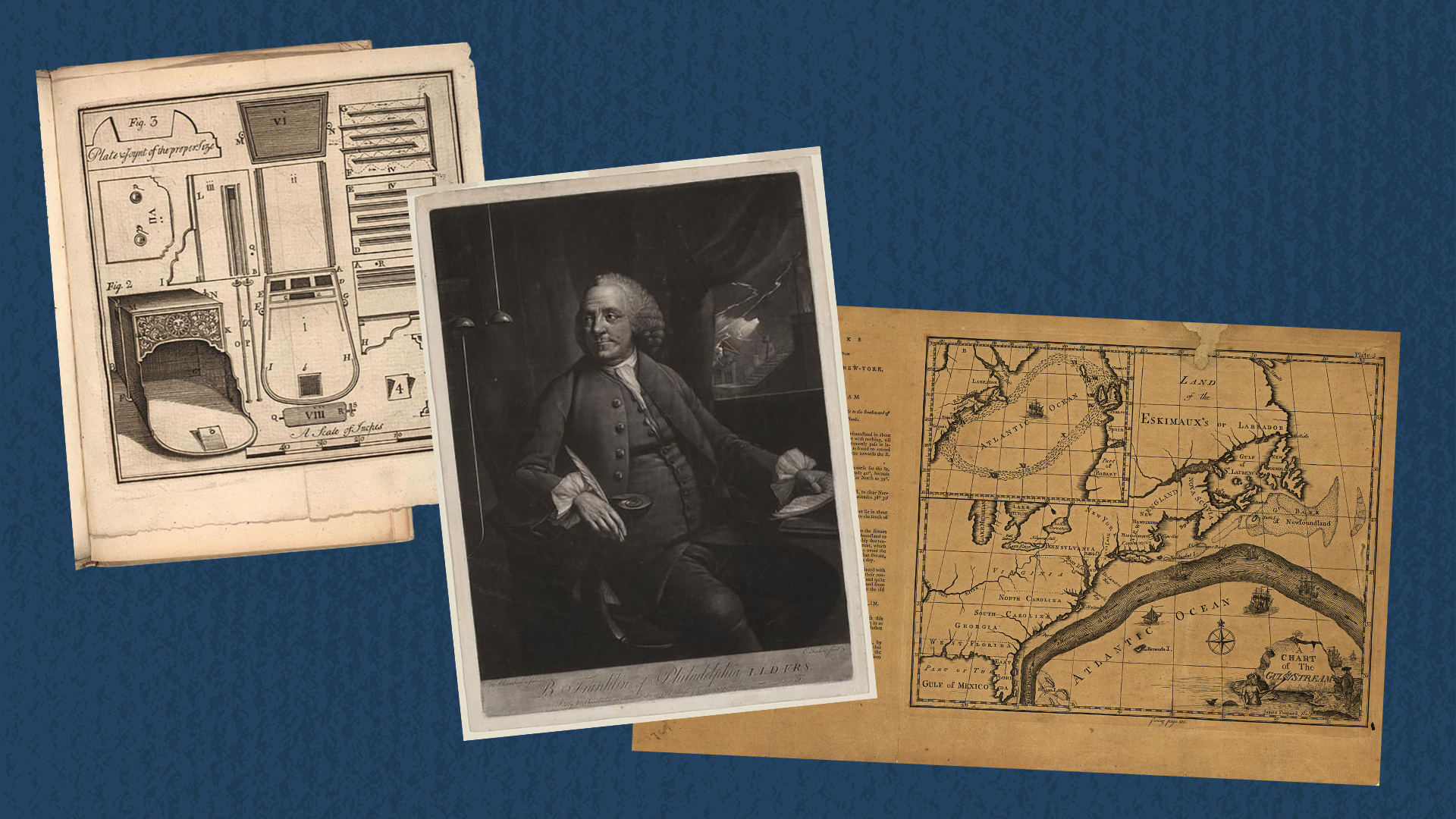

Historian Joyce Chaplin’s latest book on Benjamin Franklin (center) explores one of his lesser-known inventions: a stove (left). The science behind it helped further understanding of atmospheric phenomena such as the Gulf Stream (right), which Franklin helped map for the first time.

Images via Library of Congress; illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

When a stove’s virtues amount to more than just hot air

Science historian examines how Benjamin Franklin’s invention sparked new thinking on weather, technology

Joyce Chaplin thought she was done with Benjamin Franklin.

“But then I was reading about the Little Ice Age and the particularly bad winter of 1740 to 1741,” said Chaplin, the James Duncan Phillips Professor of Early American History. “Major harbors were reported as freezing over — in Boston, in London, in Venice. The consequence was famine in several places including Ireland, where as much as 20 percent of the population may have died — that’s a bigger toll than the more famous Great Hunger of the 19th century.

“And all along I kept thinking, ‘I know the dates 1740 and 1741 from somewhere.’”

Chaplin, an expert on early American science, technology, and medicine, eventually put things together. These were the years when Franklin — a humble printer who went on to become a world-renowned scientist, inventor, and statesman — devised the prototype for his Pennsylvania fireplace, a flatpack of iron plates colonists could assemble and insert into their hearths to improve heating.

“It was developed during this very, very cold winter as a climate adaptation,” explained Chaplin, who has written at length on Franklin’s scientific contributions. “The design was supposed to burn less wood yet make a room even warmer than an ordinary fireplace.”

Franklin went on to develop at least five separate iterations of the influential technology over half a century, moving from wood to coal for fuel. Chaplin’s newly released “The Franklin Stove: An Unintended American Revolution” finds this seemingly modest invention catalyzing new thinking on weather, technology, and comfort.

We sat down with Chaplin, who is also affiliated faculty in the History of Science Department, to ask about the book and its many lessons for the 21st century. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

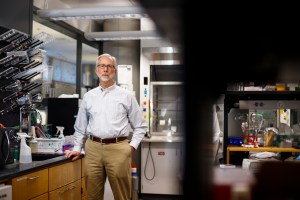

Joyce Chaplin.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

You published an intellectual biography of Benjamin Franklin in 2006 and edited an edition of his autobiography for Norton a few years later. What draws you to this 18th-century figure time and again?

The popular conception is “Poor Richard,” Franklin’s alter ego from the almanacs he published. But he’s far more complicated than that. He was the youngest son of a Boston chandler, somebody who worked with his hands making soap and candles out of animal fat. It was a completely respectable but not very distinguished background.

The classic ways of getting ahead that were available to a man like Franklin included war or some kind of military career that would advance him beyond the rank he was born to. Politics, if he could get a foot in. Writing, perhaps. Science had also become a part of popular culture, with Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle becoming household names in the wake of their big discoveries.

I think Franklin looked over all these options. He eventually looked at Newton and thought: “Why not try that route?”

Is it fair to call the Franklin stove one of his lesser-known inventions?

For the moment, I think that’s fair. A lot of people know about Franklin inventing the lightning rod. Those who need progressive glasses at some point probably know he invented bifocals. Others have heard about his more charming inventions — his swimming fins, his folding chair/step stool for reaching books in the library. But given the climate framing of this particular invention, perhaps the public will start to embrace the stove as central to his life in science.

Let’s dig into the environmental issues Franklin faced during the winter of 1740 and ’41. It was more than frigid weather.

Franklin was aware that as more settlers were arriving, being born, and spreading across the landscape, they were going to deforest the territory and make firewood more expensive and possibly even inaccessible to the poor. We have his accounts of people stealing firewood or ripping off pieces of fences.

But the most ambitious part of his plan was to make people more comfortable than ever before. And the fact that it was colder than ever before makes that a really interesting manifestation of enlightenment confidence — that humans could use science and technology to make life better, whatever the circumstances.

“Atmosphere was a relatively new word in terms of describing the envelope around the Earth, and this is what Franklin thought a good heating system could create indoors.”

How did the stove help further understanding of the natural world?

Atmosphere was a relatively new word in terms of describing the envelope around the Earth, and this is what Franklin thought a good heating system could create indoors. He explained in a self-published pamphlet how his fireplace worked through the principle of convection: that air, when it’s warmed, will expand and rise. And what you want is some kind of heat source that does this layer by layer until the entire room is warmed.

But Franklin also used this concept to explain atmospheric phenomena outdoors. He used it to explain how storm systems move up the Atlantic coast. He eventually used it to explain the Gulf Stream — how heated air moves up from the Gulf of Mexico and out over the Atlantic Ocean with a relationship to the warmer current of water underneath. When making these grand statements, Franklin would often write something like: “Just like there’s a draft of air from your fireplace to the door.” It was a brilliant strategy for making science accessible to a reading public.

Franklin is known for his late-in-life abolitionism, but your book adds one more entry to the list of ways he profited from slavery before that. What new information did you uncover?

I knew from reading my colleague John Bezís-Selfa’s “Forging America” (2004) that there had been an iron industry in the colonies, including Pennsylvania. I also had a sense from reading Bezís-Selfa that enslaved Black people performed some of the labor on these estates.

I went to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which holds most of the surviving records of the Pennsylvania iron industry, and indeed found these two enslaved men — Cesar and Streaphon — who worked in the iron establishment that made most of the Pennsylvania fireplaces.

One of these men — Streaphon — managed to buy his own freedom. That, to me, was an important indication that the desire to be free was a constant. It can be seen everywhere in early American history.

What compelled Franklin to try minimizing emissions from his stove?

He was appalled at the filthy air in places like London. So, he tried to design the last three versions of his stove to re-burn smoke — by sending the smoke that would otherwise be ascending into the chimney back into the fire.

Franklin pointed out, correctly, that smoke is really particles of unburned fuel. If you could burn it again, at least it’s more efficient. You’re wasting less fuel. You’re putting less junk into the air. He’s so concerned with doing this that a friend teases him for being “a universal smoke doctor.”

To me, it’s a very interesting statement about questioning the level of emissions that already seemed to be compromising human health. Of course, what gets identified decades after his death in 1790 is that some of these emissions are invisible. The American scientific observer and experimenter Eunice Foote documented the climate-altering effects of CO2 in 1856.

You connect today’s techno-optimism to Franklin and other inventors of his era, who thought they could invent their way out of a climate crisis. What lessons does your book hold for inheritors of this philosophy?

I don’t think Franklin meant to validate burning coal in the industrial sense, but he did validate it as an energy source. That says to me: Don’t pick the quick and obvious solution. Or at least be suspicious and monitor how it’s doing.

We should be wary of this silver bullet fantasy, that we need to find just one thing to sequester carbon out of the atmosphere. Or that we can just shift to sustainable energy in the absence of climate mitigation before chemical changes in the atmosphere become too dire.

We’ll need more than one inventor, one device, one hero. There are just too many variables for one solution to be possible. We need to modify our course as soon as possible with a lot of solutions working together.