Tech has changed. Dating? It’s complicated.

Illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

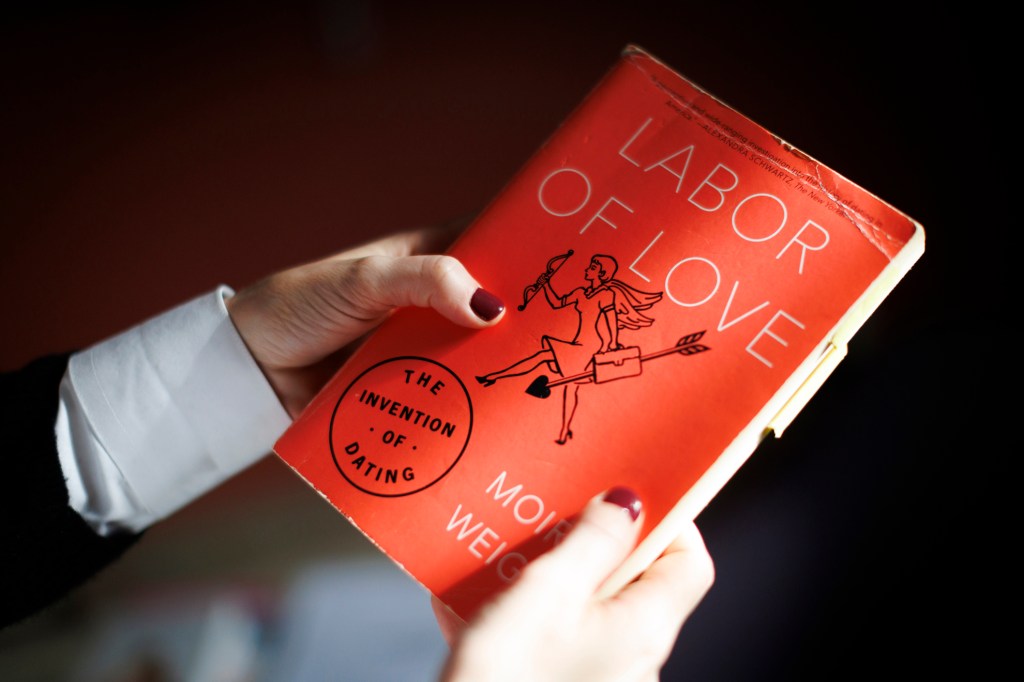

If you think algorithms and chatbots are ruining romance, ‘Labor of Love’ author has a history lesson for you

Moira Weigel began researching the history of dating in the early 2010s during a pivotal cultural moment in the U.S. The effects of the Great Recession were still deeply felt, mobile phone apps were taking off, and the internet buzzed with think pieces dissecting the state of modern romance.

“There was this whole discourse about how the recession was impacting men and women differently, undermining so-called traditional gender roles,” said Weigel, assistant professor of comparative literature. “At the same time, there was a lot of conversation about the impact of social media on romantic relationships. The intersection of those topics made me interested in this subject.”

The result was her first book, “Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating” (2016), which sought to challenge some pessimistic ideas that match apps were bringing about the “end of dating” or changing it beyond recognition. Instead, she argued, courtship had evolved with women’s entry into paid work and with consumer capitalism.

Weigel, who joined Harvard’s faculty in 2024, is teaching “Media, Technology & Social Change” and “Global Media” in the Department of Comparative Literature. While her current research focuses on data-driven technologies such as social media and marketplace platforms, and new developments in AI and machine translation, she remains fascinated by trends in tech and courtship.

In this edited conversation with the Gazette, Weigel discusses how dating has evolved over the years and the surprising historical precedent for chatbot girlfriends. (Spoiler alert: Dating anxiety is not just a modern struggle.)

Today, many dating apps boast highly personalized algorithms aimed at narrowing search parameters. What are the implications of such a high degree of personalization?

There is a promise that comes with these apps, particularly as their user base has gotten larger and algorithms more sophisticated and dynamic, that they are going to make courtship more efficient. Apps promise to provide a larger selection of possible partners than, say, your local bar, and to sort them into personalized results. The technical logic is not unlike that of online marketplaces.

But dating apps did not invent this. I always like to push back against thinking about these questions too techno-deterministically, as if technology alone makes culture change. In my research for “Labor of Love,” I looked at video dating libraries from the 1980s, where people would record VHS tapes of themselves and file them in a collection where members could go search according to different traits. People have placed personal ads in newspapers for centuries. The earliest versions of Match.com or OKCupid mostly used elaborate multiple-choice questionnaires to sort people. Now most of the famous dating apps use dynamic forms of machine learning to consider different data points and adapt based on user behavior. Desires for scale, efficiency, and personalization are older than algorithms.

How has technology shaped how people date and find love?

The history of love and the history of technology have always been intertwined: We could talk about the automobile, or the telephone, or the steam engine as technologies that changed courtship. But among contemporary, data-driven technologies I think one very important change came with the normalization of mobile phone apps. These had this really interesting effect of blending the online and offline. When you look back at so-called “cyber-dating” in 1990s shortly after the World Wide Web was popularized, many people expressed this sense that the internet was another world that you went into through your desktop computer. A lot of the moral panic about people looking for sexual or romantic connections online revolved around the idea that such connections were “unreal” and would disconnect you from relationships that were supposed to be more appropriate and meaningful. Mobile phones and social apps have now totally eroded the boundary between online and offline. Dating has become something you can engage in on your phone, between responding to a work email and ordering a taxi or a burrito. That produced a bunch of different changes which are hard to disentangle.

What were some of those changes?

I think it removed a lot of the stigma that had been attached to online dating or older practices like video dating. I think it “re-rationalized” courtship, making people more comfortable with the idea that finding a partner was not entirely a matter of spontaneity, instincts, and effortlessness, that there might be some social scripts and search parameters involved.

Throughout history, has finding a partner been more about romantic spontaneity or a rational search process?

In the scope of human history, the idea of choosing partners based on chance encounters and their own personalities or sensibilities is a very new one. It emerged in the West, in 18th- and 19th-century Europe and the U.S., alongside political and industrial revolutions that produced new ideals about individuality, society, and freedom.

Before industrialization, if you worked on a farm with your extended family, it was rational to marry the guy who lived on one of the next farms and merge your property and labor. Besides, where else were you going to meet someone? Economic and technological changes changed the meaning and function of love and marriage. It’s no accident that so many of the great 19th-century novels were about the difficulty of making personal attractions and emotions the basis of marriage. Think of “Elective Affinities” (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe), “Madame Bovary” (Gustave Flaubert), or “Anna Karenina” (Leo Tolstoy).

Over time, there emerged an ideal of attraction and love as “anti-practical,” because it’s supposed to be an expression of freedom, excitement, and possibilities of modern life. Charles Baudelaire’s “À une passante” (“To a Passerby”), about walking past a stranger on the street, captures the idea that you might see anyone in a city, that anyone might be the love of your life, or you might never see them again. These ideals cast romance as the opposite of calculating.

Algorithms literally calculate, and dating apps use algorithms to optimize for certain kinds of partners. To me, that’s where dating apps bring in explicit rationalization that feels different from the dominant romantic ideals of the past century or two.

“The history of love and the history of technology have always been intertwined.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

How are technologies like generative AI and chatbots impacting how people date?

What I have seen around dating apps mirrors what you see in all sectors of the digital world or the economy. I’ve anecdotally heard about people using chatbots to generate lots of messages to people or using AI to sort such messages. For years there has been this trend toward virtual dating assistants, who would look through people for you, like matchmakers, and it makes sense that folks might use GPTs to do some of that.

The other thing that people talk about is chatbot girlfriends and boyfriends. That, of course, has a very old cultural history.

Could you say more about that?

There have been so many different literary representations of this fantasy of creating your perfect partner — a dream come true that also usually turns out to be a kind of nightmare. We could look at the Greek and Latin myth of Pygmalion. We could look at so many narratives of automata in 19th-century Europe, from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman” to Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s “The Future Eve.” To go way back, we could talk about Eve being made from Adam’s rib to be his helpmate. The depth of that trope of a human (usually a man) building the ideal partner is fascinating to me. It comes up in movies, too: classic films like Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” (1927) or Ridley Scott’s “Blade Runner” (1982) or more recent ones like “Her” (2013) and “Ex Machina” (2014) or that HBO show “Westworld.” All these stories explore what humans want in one another, but also how we project our desires onto machines and other arts. We can develop deep attachments and emotions to made objects, but there’s always an undercurrent of danger and loss that comes with that kind of mastery. So even though something like Replika, the chatbot girlfriend, does not perhaps seem like an intellectually sophisticated thing, it ties into this deep history.

What about for people who are frustrated with the culture of modern app dating? Is there historical precedent for this?

A sense of crisis lies deep in the DNA of dating. There are no moments in the history that I researched where people were saying, “It’s great! It’s fine! I’m not worried about it!” At every moment there’s an anxiety about dating, which also becomes the occasion for a lot of cultural production, too: self-help books, romantic comedies, YA novels, not to mention all the things companies sell people to try to help them feel more desirable. That sense of anxiety is really culturally and economically productive. And so, even as it changes, it seems to find a way to carry on.