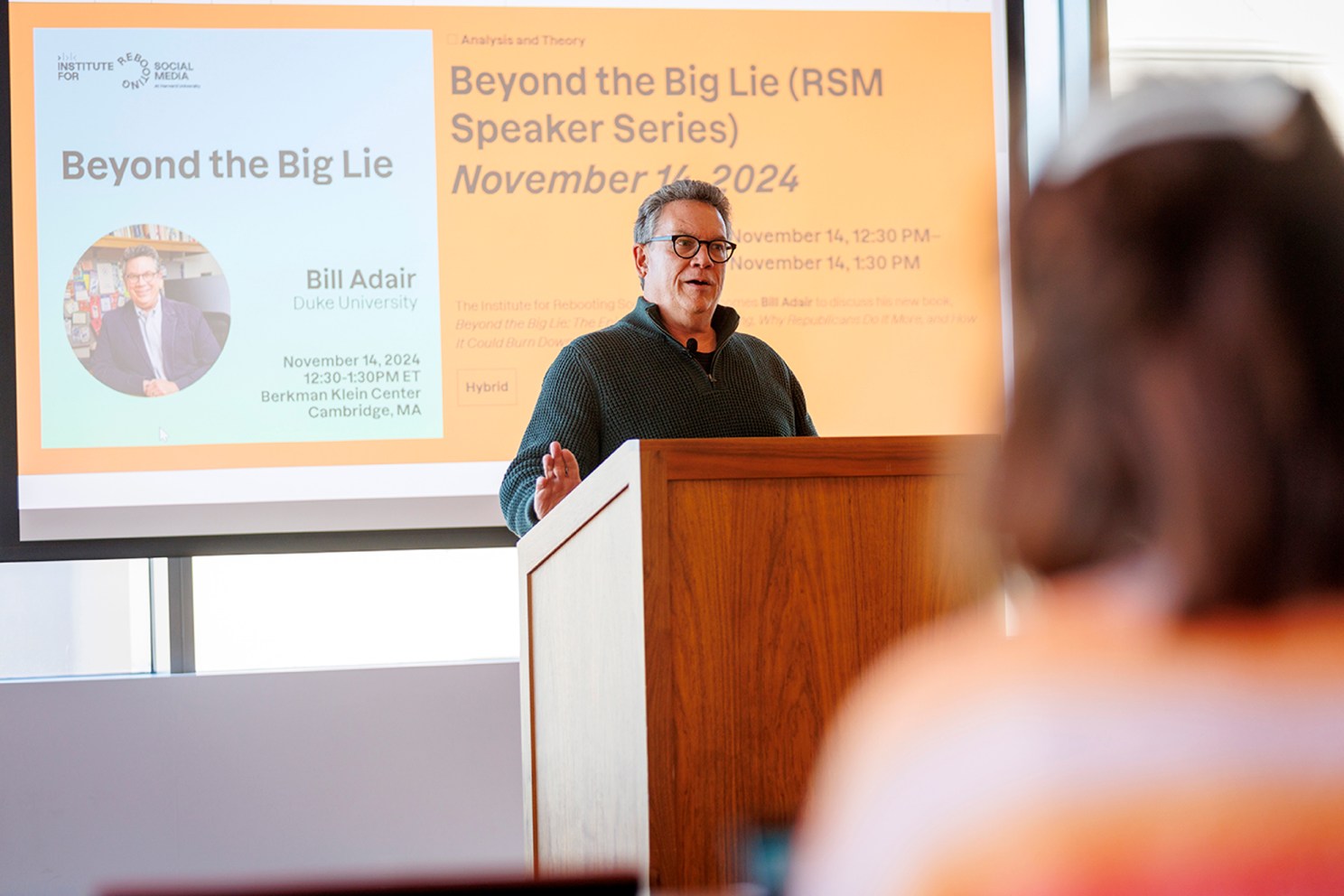

Bill Adair.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Rising ‘epidemic of political lying’

Founder of PolitiFact discusses case studies from his new book that reveal how we got to where we are now

Many Americans feel like the spin and outright lying in politics has gotten worse in recent decades. And that it’s not a good thing.

Bill Adair agrees. The founder of PolitiFact, the Pulitzer Prize-winning, fact-checking website, looks at the problem in new book, “Beyond the Big Lie: The Epidemic of Political Lying, Why Republicans Do It More, and How It Could Burn Down Our Democracy.” He was on campus recently to detail his thoughts in an event at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society.

“For many years, no political journalist that I’d ever worked with nor myself had ever asked a politician: Why do you lie? And so it’s sort of this topic that is omnipresent and yet never discussed. I decided to discuss it, and I decided to ask politicians about it,” said Adair, the Knight Professor of the Practice of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke University.

“They make a calculation — am I going to gain more from making this statement that is false than I’m going to lose. It’s that simple.”

Following several years of research and reporting, Adair ended up zeroing in on about a half dozen people’s stories in his book as case studies that reveal what he calls “truths about lying.”

He also laments that calling out the fabrications and misinformation has not worked to alter the behavior of political actors and that the internet has made it all worse.

“Lying is not a victimless crime. When politicians choose to lie, there are often people who suffer, and often an individual who suffers a great deal, often someone whose reputation is damaged, whose life is turned upside-down,” he said.

At the event, Adair told the story of Nina Jankowicz, a disinformation researcher and writer who had been put in charge of an advisory board within the Department of Homeland Security in 2022 meant to help combat the spread of false information online. She ended up resigning under pressure after opponents of the board spread conspiracy theories online that her real goal was to crack down on free speech.

Adair also recounted the tale of Eric Barber, a city councilor from West Virginia, who became radicalized through Facebook to join the group that attacked the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Adair said that despite serving jail time, Barber still believes that the 2020 election was stolen and Donald Trump won.

Adair also discusses the case of Stu Stevens, a strategist for the 2012 Mitt Romney campaign. Stevens’ group produced an ad making the false claim that then-President Barack Obama was responsible for Jeep shifting production from Ohio to China. Jeep officials publicly stated that claim was false, noting that the company was expanding operations in China but “the backbone of the brand” would remain in the U.S. Adair said Stevens refused to admit the ad was wrong, insisting “it’s technically true.”

So why do politicians bend the truth? And where did it start? According to Adair, it’s a very calculated decision.

“They make a calculation — am I going to gain more from making this statement that is false than I’m going to lose?” he said. “It’s that simple. They want to build support for the base, and they believe that lie, in some small way, will help them do that.”

While both sides lie, Adair says his research finds Republicans do it more often. He writes in his book that from 2016 to 2021, 55 percent of the statements made by Republicans and investigated by PolitiFact were false, while 31 percent of those made by Democrats were.

“I asked that question of a whole bunch of Republicans and former Republicans who were willing to talk to me, and I heard a lot of answers,” Adair said. “One was that it’s just become part of their culture.”

“We went state by state, and we found that in half the states there are no political fact-checkers. That’s like having interstate highways where there’s no risk of getting a speeding ticket.”

Denver Riggleman, a former GOP congressman from Virginia, told Adair that Republicans view their work as part of an epic struggle, and that in that struggle anything is OK.

Adair took pains, however, to underscore that Democrats also lie. For example, a PolitiFact check on Joe Biden in May finds he wrongly stated that the rate of inflation he inherited when he took office was much higher than it actually was.

Overall, he went on to say, fact-checking is not working.

“Fact-checking is not stopping the lies. Fact-checking is not putting a serious dent in the lies,” Adair said.

Adair pointed to a study he’s been a part of at Duke, about states where there is state and local fact-checking.

“There’s plenty of fact-checkers who check politicians when they are running for president, but what about the senators and governors and members of the U.S. House?” he said. “We went state by state, and we found that in half the states there are no political fact-checkers. That’s like having interstate highways where there’s no risk of getting a speeding ticket.”

That leads Adair to his first recommendation.

“We need to be creative in getting [fact-checking] to more people, in using it as data so that we can suppress misinformation,” he said. He added that in addition to increasing the volume of fact-checkers in underreported areas, there needs to be more conservative organizations doing their own fact-checking.

“This can’t just be for people who listen to NPR and read The New York Times,” he said.

Adair suggests that AI might help fact-checkers by allowing them to track lies across multiple platforms. He also pointed to efforts by Facebook to fact-check posts on their site.

“I think that we need to reboot how we do this and how we think about this, because the lies are running rampant,” he said.