Breakthrough technique may help speed understanding, treatment of MD, ALS

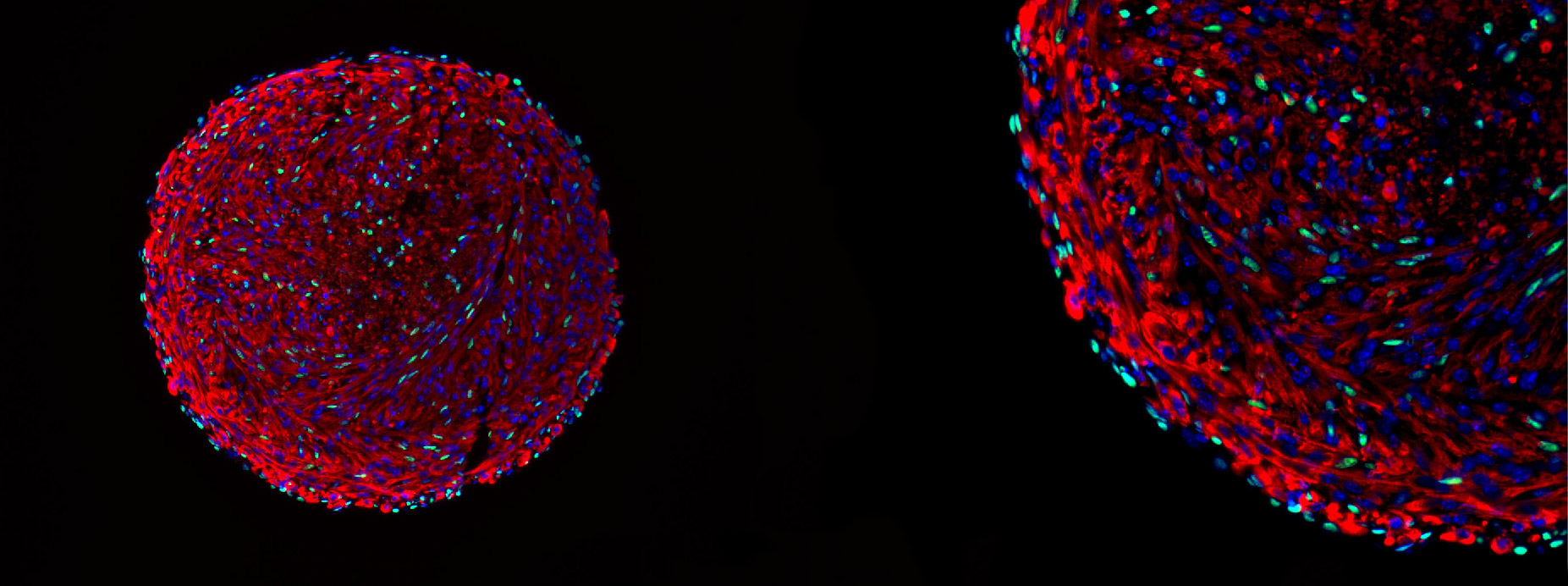

Microscopy image of a skeletal muscle organoid. The green cells are in vitro-derived satellite cells.

Courtesy of Feodor Price

3D organoid system can generate millions of adult skeletal-muscle stem cells

Harvard researchers have pioneered a groundbreaking method for generating large numbers of adult skeletal-muscle satellite cells, also known as muscle stem cells, in vitro.

The development could help speed the understanding and treatment of a range of skeletal muscular disorders, including muscular dystrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

The new 3D organoid culture technique for the satellite cells, detailed in Nature Biotechnology, also provides a powerful tool for studying muscle biology.

“People will be able to do all these engraftment and regeneration experiments because suddenly, you have millions of cells,” said co-author and Harvard research scientist Feodor Price. “Go play with them, study them, look at your favorite genes and pathways in your labs.”

Price worked with Lee Rubin, professor in the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology and co-chair of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute Nervous System Disease Program, to pioneer the lab-derived satellite cells that closely resemble native adult stem cells and are responsible for skeletal muscle growth and regeneration.

When transplanted into mouse muscle, the cells were able to engraft, repopulate the stem cell niche, persist long-term, and regenerate muscle after repeated injury — all key functions of native satellite cells.

Lee Rubin and Feodor Price.

Photo by Jon Ratner

Their unique approach overcomes the challenge of maintaining satellite cells’ regenerative capabilities when cultured outside the body with traditional methods. “Once you take them out of the body, they basically stop being a stem cell,” Price explained.

Price elaborated that when the muscle stem cells are cultured with the goal of increasing their numbers, they proliferate rapidly but then spontaneously differentiate into myoblasts (muscle progenitor cells), losing their original functional capacity. This leads to ineffective muscle repair and maintenance when the cells are transplanted back into the body.

The team’s breakthrough in maintaining the satellite cells’ regenerative capabilities came from the innovative use of 3D organoid culture techniques. By placing mouse myoblasts into spinner flasks, the researchers could generate organoids containing differentiated muscle fibers and a population of cells expressing the key satellite-cell marker Pax7.

The presence of this important transcription factor and the organization of the structure within the organoid were indicators of their method’s success.

“We are confident that we have successfully recreated the satellite cell niche,” Price said. “And because of that, we were able to coax cells within that organoid to dedifferentiate back to the satellite cell state. In essence, we have created satellite cells in vitro, a significant achievement that holds great promise for the field of regenerative medicine and muscle biology.”

Extensive in vitro and in vivo characterization demonstrated that these stem cells closely resemble bona fide satellite cells, including their small size, quiescence, and expression patterns of key genes and epigenetic marks.

They are, however, not identical to native cells. RNA and DNA analysis revealed that the lab-generated cells have an intermediate transcriptional and epigenetic profile between satellite cells and myoblasts.

Most importantly, though, when transplanted into mouse muscle, the cells were able to engraft, repopulate the stem cell niche, persist long-term, and regenerate muscle after repeated injury — all key functions of native satellite cells.

The researchers were also able to generate the satellite cells from human myoblasts, including highly passaged commercial cell lines. This has important implications for the development of cell therapies, as working with human tissue is difficult, and large numbers of functional satellite-like cells can now be produced in vitro.

This research was supported by the Blavatnik Biomedical Accelerator and the strategic alliance between Harvard University and National Resilience established by Harvard’s Office of Technology Development (OTD) to advance the research toward commercialization opportunities.

Building on these advancements, the research team laid the groundwork for a collaborative project with other Harvard labs to model the entire neuromuscular circuit, with potential applications for conditions like spinal muscular atrophy, ALS, and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy.

“Our lab has spent years working on the ‘neural’ side of neuromuscular diseases,” Rubin said. “We are now looking forward to a time when we can generate an entirely new circuit extending from the spinal cord to highly functional muscle.”