Getting ahead of dyslexia

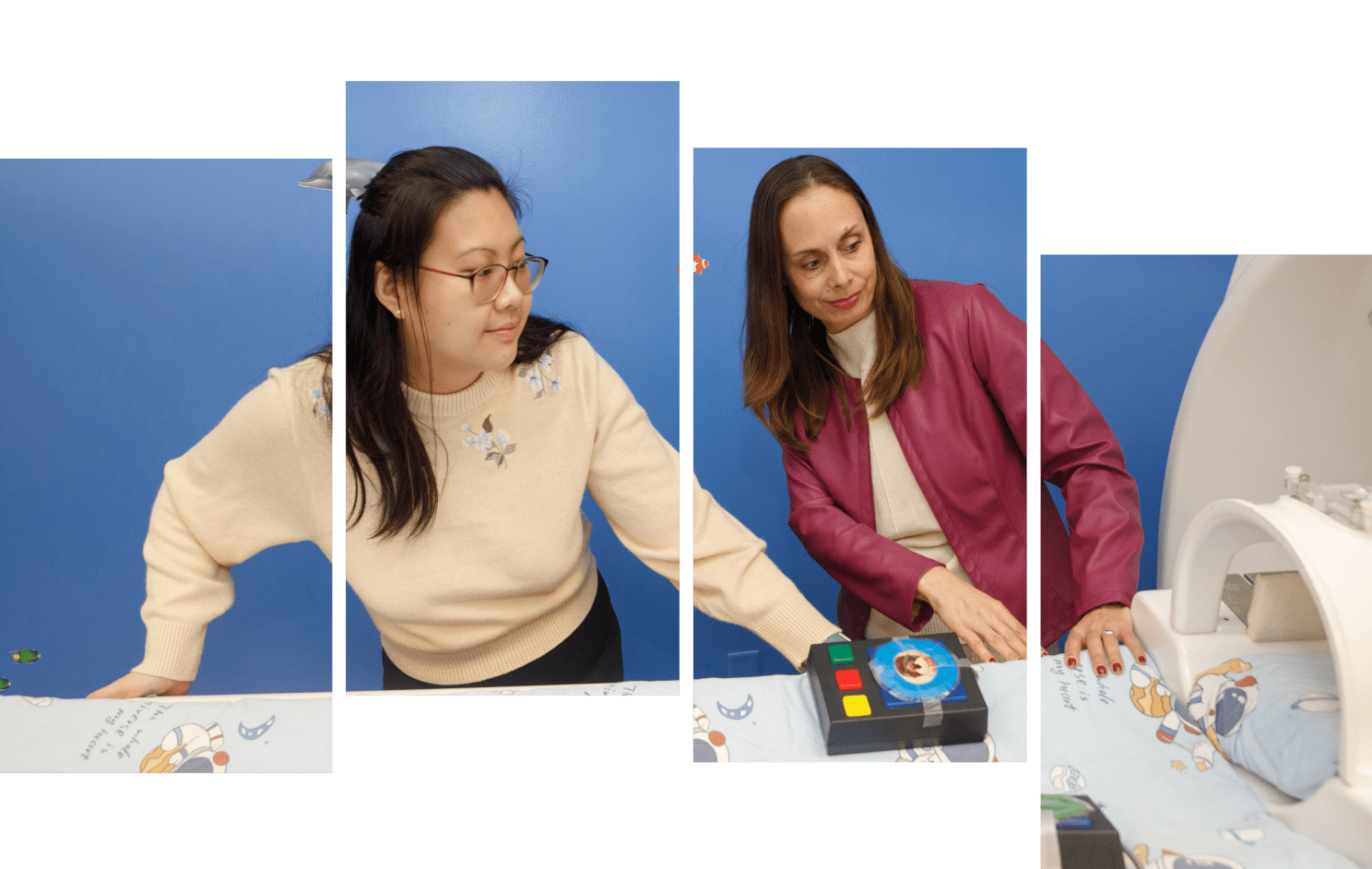

Nadine Gaab and research assistant Megan Loh (left) demonstrate a mock MRI machine they use to prepare children for the real thing.

Photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer; photo illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

Harvard lab’s research suggests at-risk kids can be identified before they ever struggle in school

Final installment in a four-part series on non-apparent disabilities.

For more than 15 years, Nadine Gaab’s lab has been unlocking secrets of how young brains develop, with an emphasis on non-apparent disabilities, or physical or mental conditions that are not immediately obvious to others.

“It is very challenging and rewarding at the same time,” said Gaab, associate professor of education. “The best way to examine how a child learns is to follow them closely while they are learning and to look at all aspects of their learning, including brain development, behavior, genetics, and environment.”

The Gaab Lab, based at the Graduate School of Education since 2021, focuses on atypical learning trajectories, particularly those of children with dyslexia, a language-based learning disability. A key question the lab is tackling is pinpointing when brain characteristics associated with dyslexia manifest.

Scientists have long known that people who struggle with reading often show atypical brain structure and function. “The question was, ‘Is that development in response to struggling every day in school, or is it something that develops before their first day of kindergarten?’ That’s a really important question for policy,” she said.

“If everyone comes to kindergarten with a ‘clean slate’ brain and then changes in response to instruction, then you have to monitor them after they start school and try to catch kids who fall off the bandwagon. But if you can show that some of these atypical brain developments happen before the first day of kindergarten, you should find them before they start and intervene in response so that they will never struggle.”

In its Boston Longitudinal Dyslexia Study (BOLD), started in 2007, the lab found that some of the brain characteristics reported in the third or fourth grade were already present in preschoolers. The findings piqued Gaab’s curiosity and pushed her team to launch a follow-up study in 2011 to see how early these markers could be seen.

In its ongoing BabyBOLD study, Gaab’s team enrolls infants between 3 and 8 months old who have a familial risk for reading disabilities — perhaps a parent or sibling has dyslexia — and monitor them until elementary or middle school. They’ve found that some atypical brain characteristics involving white matter (where information and communication is exchanged), connectivity patterns, and other measurements found in older children are already present as early as infancy.

“If you can show that some of these atypical brain developments happen before the first day of kindergarten, you should find them before they start.”

Nadine Gaab

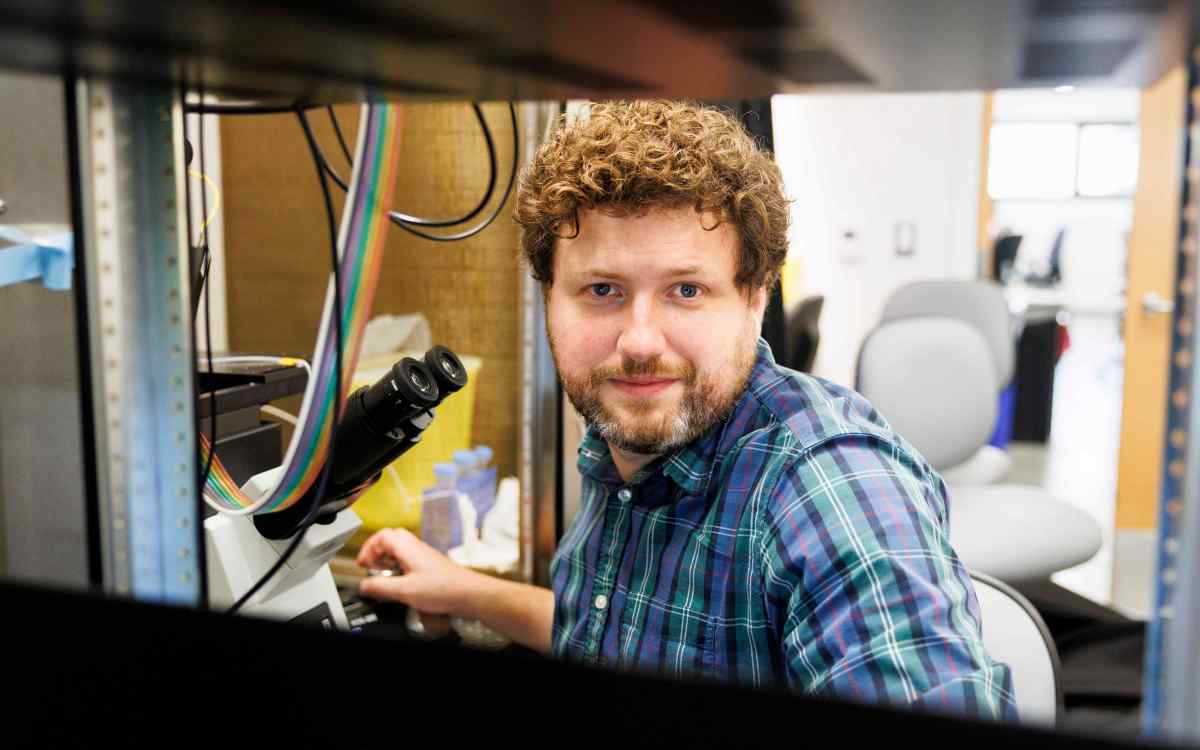

“A lot of the importance in the work from the Gaab Lab has to do with seeing that there are some developmental differences in children prior to the start of formal reading instruction,” said Ted Turesky, a researcher at the lab. “It shows policymakers that there are these differences and that we need to address them before reading instruction starts so interventions can be more effective.”

This is key, Gaab said, because until recently, elementary schools across the country have relied on a “wait to fail model” for students with reading disabilities. Gaab said this reactive model often leaves children with low self-esteem, negative experiences with learning, and even shame. Her lab’s research instead promotes a proactive model that aims for earlier interventions.

“Every child has the right to read well. Every child has the right to access their full potential,” Gaab said. “This society is driven by perfectionism and has been very narrow-minded when it comes to children who learn differently, including learning disabilities.”

Until recently, Gaab said, many elementary schools have relied on a “wait to fail model” that often leaves students with low self-esteem, negative experiences with learning, and shame.

Workdays in the lab sometimes stretch from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Three-hour sessions with young learners include behavioral monitoring, psychometric testing, brain scans, and speech assessments.

Ahead of the brain scans, Gaab’s researchers have their young subjects experiment with a mock MRI while watching a movie like “Kung Fu Panda.” “Going into the MRI can be a lot for the kids,” research assistant Megan Loh explained. “What we have found to be the most effective strategy is just to treat it like a really fun game where they have to stay super still.”

Gaab works closely with the learning disability community and grassroots parents’ organizations, as well as state and federal agencies. The lab recently collaborated with Decoding Dyslexia Massachusetts, a parent-led group that advocates for systems-level changes in education and dyslexia prevention legislation, on research dedicated to early identification of children at risk of developing reading difficulties and the need for screenings at school.

The organization was among nearly a dozen groups that supported former state Secretary of Education James Peyser’s June 2022 measure to require early literacy universal screenings in schools and districts. That mandate officially took effect in July 2023.

“There is a large number of kids globally who have disabilities and one big subgroup of this is invisible disabilities, and often invisible disabilities are completely ignored,” Gaab said. “These are brilliant individuals and it’s really important that we bring invisible disabilities to the forefront and make sure that we provide interventions and accommodations to them.”

Resources

- University Disability Resources serves as the central resource for disability-related information, procedures, and services for the Harvard community.

- Students who wish to request accommodations should contact their School’s Local Disability Coordinator.

- The 24/7 mental health support line for students is 617-495-2042. Deaf or hard-of-hearing students can dial 711 to reach a Telecommunications Relay Service in their local area.

- Harvard Law School Project on Disability