Taylor Swift, the Wordsworth of our time?

Harvard English Professor Stephanie Burt teaches “Taylor Swift and Her World.”

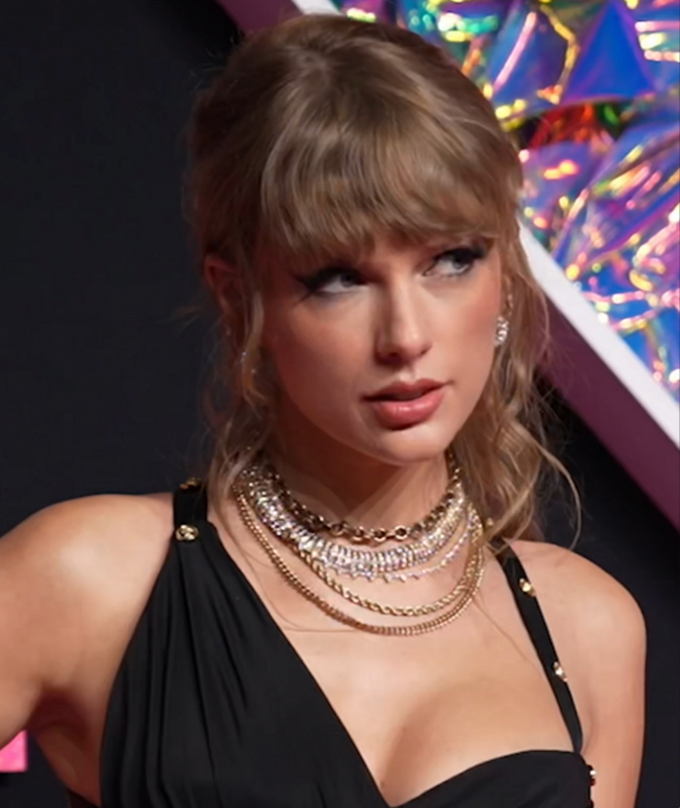

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

New English course studies pop star’s lyrics alongside classic literature

It turns out Taylor Swift could keep company with the Romantic-era poets.

On a recent Monday afternoon, Professor Stephanie Burt asked some 200 students — packed into Lowell Lecture Hall for the popular new English course “Taylor Swift and Her World” — to consider their role as listeners to “Fifteen,” the second track off the superstar’s second album, “Fearless.”

In the song, Swift presents herself as a teenage girl who’s both relatable and aspirational with lyrics that reflect upon high school, friendship, and dating. Burt compared the song’s reflective qualities to William Wordsworth’s 1798 poem “Tintern Abbey.”

“She’s establishing herself as a kind of ally for us, what the poet and literary theorist Allen Grossman calls a ‘hermeneutic friend,’” said Burt, the Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor in the Department of English. Or in other words, “the literary or musical text that you’re getting into is going to help you out, it simultaneously knows more than you do, and knows what’s going on with you.”

The course resonates with the many students who have been fans since childhood. Seated in tiered rows on the main floor and in the balcony, they nodded along intently with the lecture, occasionally laughing when Burt threw out an insider Swiftie reference.

It’s the largest class Burt has ever taught — and the largest taught in the arts and humanities this spring. The professor, who has long wanted to create a course centering the works of a songwriter, knew “all too well” that it was time to examine Swift’s writing through an academic lens.

“She’s one of the great songwriters of our time,” Burt said. “If she weren’t, she wouldn’t be this popular. And I love the idea that we’re going to spend this much time with her music.”

The syllabus is organized around the “eras” of Swift’s career, starting with her 2006 debut album and progressing to her most recent. Students examine themes of fan and celebrity culture, whiteness, adolescence, and adulthood alongside songs by Dolly Parton, Carole King, Beyoncé, and Selena, and writing by Willa Cather, Alexander Pope, Sylvia Plath, and James Weldon Johnson.

“The best way to get someone into something is to connect it to something they already love,” Burt said, in an interview before class. “I do think there’s going to be a lot more Harvard students reading Alexander Pope because he’s in the Taylor Swift course than if he only showed up in courses that were entirely dead people.”

Burt explained that she is teaching Swift as a songwriter rather than a poet because writing for music is its own literary form, one that requires different skills than writing for the page. Burt and teaching fellow Matthew Jordan regularly unpack songs on the piano during class. During a recent class, the whole room broke out into spontaneous song as Jordan performed “Love Story.”

“Usually, poetry means works of art that use nothing but words that are created to be read on a page that do not have to be read aloud by the author,” Burt said. “Songwriters are writing for a melody; they are writing for singing interpreters. You are not getting all that you can out of a song if you are reading it on a page.”

‘Tortured poets’ department?

May I behold in thee what I was once, My dear, dear Sister! Knowing that Nature never did betray The heart that loved her; ’tis her privilege, Through all the years of this our life, to lead From joy to joy: While here I stand, not only with the sense Of present pleasure, but with pleasing thoughts That in this moment there is life and food For future years. And so I dare to hope,

Wish you could go back And tell yourself what you know now But I’ve found time can heal most anything And you just might find who you're supposed to be Well, in your life you’ll do things Greater than dating the boy on the football team I didn't know it at fifteen

What common themes do you see in these excerpts from William Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey” and Taylor Swift’s “Fifteen”? Listen to the professor’s take below.

transcript

Transcript:

STEPHANIE BURT: She [Taylor Swift] is far from the first or the only writer who has written looking back at her younger self and addressing someone else — a friend, a specified reader, an audience — as a younger version of themselves. “I’m going to tell you what I wish someone had told me when I was that age, because I look at you — listener, reader, sister named Dorothy — and I see myself when I was that age, and by the way, I’m really close to that age. I’ve only grown up a little. I’m going to show you how that works.” That is a central trope of the literary movement which generates “tortured poets,” which we call Romanticism.”

Cormac Savage ’25, a concentrator in Romance languages and literatures and government, has been a Swift fan since age 6, when he received a platinum edition copy of “Fearless” for Christmas. So when he saw the course listing, he knew immediately that it was the one.

“I think I’ll come out of this English class with a greater knowledge of music as a byproduct of studying literature, which is a really unique point of this class,” said Savage, who is looking forward to reading Wordsworth and comparing his poetry to Swift’s album “Folklore.”

Jada Pisani Lee ’26, who is studying computer science, has also been a fan since elementary school. The sophomore said she enrolled in the class to learn more about Swift’s impact on culture, from music to style to copyright law.

While some critics may not consider Swift classically worthy of English class analysis, Burt politely disagrees.

“Half the English-language authors we now think of as ‘classic’ and ‘high culture’ and ‘serious’ were disparaged because they were popular and doing the ‘pop thing’ in their time,” Burt said. “Often the ones who were disparaged because they were doing the ‘pop thing’ were authors who were writing for women when serious prestige classics were the domain of expensively educated white men.”

Stephanie Burt

“Half the English-language authors we now think of as ‘classic’ and ‘high culture’ and ‘serious’ were disparaged because they were popular and doing the ‘pop thing’ in their time.”

The professor hopes students will gain not only a deeper appreciation for Swift but a new set of tools for literary and cultural analysis and a greater engagement with authors beyond the pop star.

“If I were not able to connect Taylor’s catalog to various other, older works of literature, I wouldn’t be teaching this class,” Burt said. “But I also wouldn’t be teaching this class if I didn’t really love her songs and find her worthy of sustained, critical attention. She really is that good.”