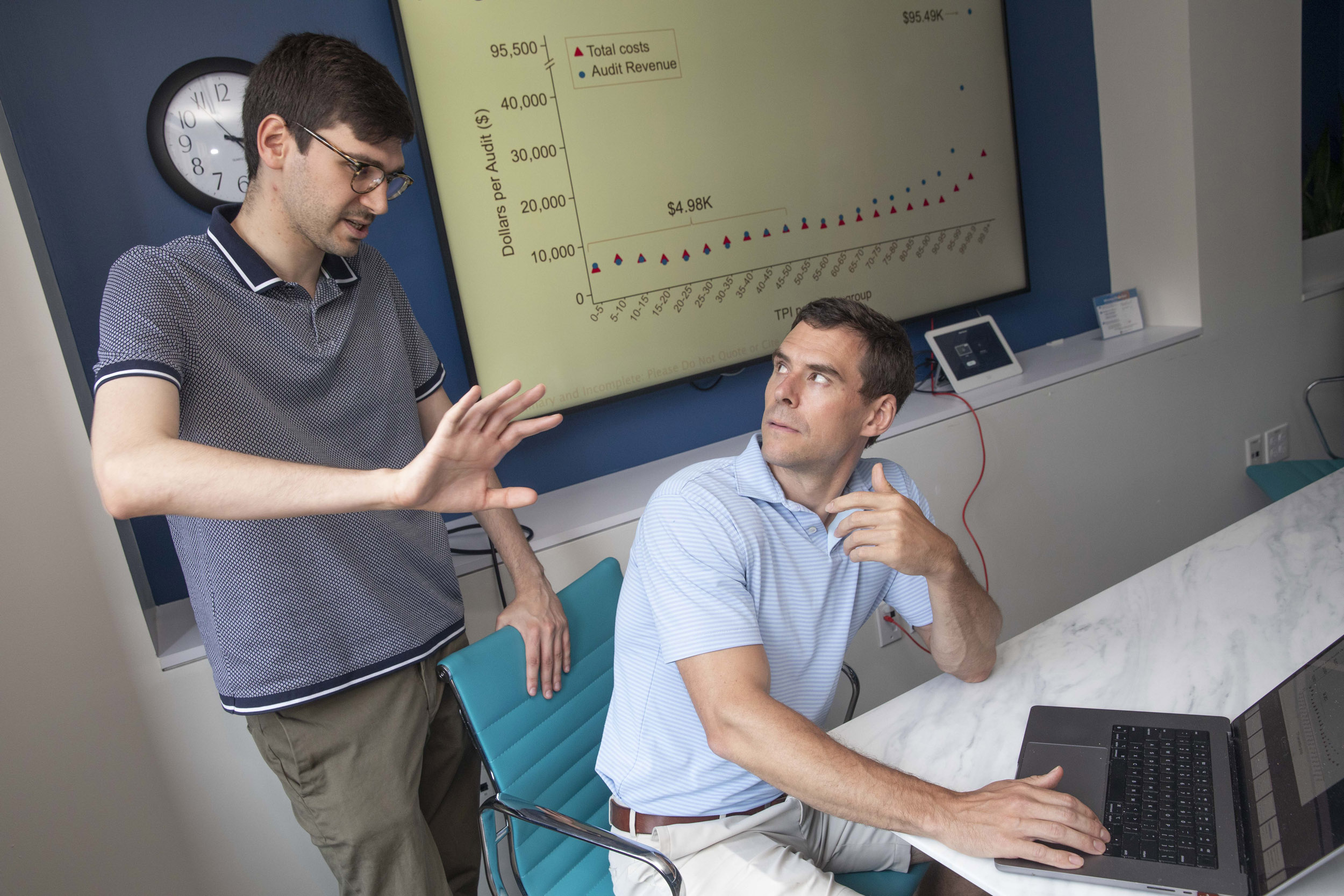

Ben Sprung-Keyser (left) and Nathaniel Hendren explain what the government gains when it invests in a tax audit, particularly audits of higher-income taxpayers.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Turns out IRS audits of wealthy offer terrific return on investment for taxpayers

New research shows reviews, which have become partisan football, yield some immediate payback, bigger long-term gains due to deterrence

Audits by the Internal Revenue Service have long helped claw back funds needed for the functioning of government. But those in-depth assessments of taxpayers — especially the in-person ones — come at a significant cost to the IRS.

“There are a lot of open questions about how best to raise government revenue,” noted Nathaniel Hendren, a former Harvard economics professor who just started working at MIT. “Audits have been recently at the forefront of this debate,” he added, with congressional Republicans moving repeatedly this year to slash IRS funding, arguing it would both save costs and eliminate some red tape for consumers.

It turns out auditing is one government investment that pays off. A new working paper, co-authored by Hendren and published last month by the National Bureau of Economic Research, shows that audits, particularly of higher-income taxpayers, raise significantly more money than they cost.

Specifically, the paper concludes that audits cost more than previously estimated, owing to everything from training to computers and the office space needed for in-person meetings. But the revenue raised more than makes up for these expenses, mostly because audits act as a powerful deterrent to tax evasion for years to come.

“When you audit somebody, you get some amount of money at the time of the audit,” said Hendren. “But we estimate that you get three times more than from the initial audit in the subsequent 14 years.”

Co-author Ben Sprung-Keyser ’23, an incoming postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard’s nonpartisan research and policy institute Opportunity Insights, explained how it works. “If the IRS audits someone today and that person learns that they are not able to claim certain deductions or are required to report additional income, it might impact the taxes that they pay in the future,” he said.

That proved to be especially true for audits of higher-income earners, even though those audits cost more. “Audits become more complicated and more expensive at the top of the income distribution,” explained Sprung-Keyser, who is also co-director of the nonprofit, nonpartisan Policy Impacts. “They take more hours. They’re conducted by employees who are of a higher pay grade and therefore more expensive. But it turns out the revenue raised from those audits is even greater.”

By mapping audit costs and returns across the income spectrum, he continued, “We saw very clear evidence that the return from audits at the top of the income distribution really exceeded by quite a bit the returns at the bottom of the income distribution.” With the top 10 percent of earners, they found, audits have the potential to return more than $12 for each $1 spent.

The research team, which also included the University of Sydney’s Ellen Stuart (a former Harvard postdoc) and the Treasury’s William C. Boning, was able to come up with these more detailed numbers due to access to data collected by the U.S. Department of the Treasury. “We were grateful that folks at the U.S. Treasury Department were willing to work with us,” said Hendren.

Their paper has clear policy implications. “The Congressional Budget Office, for example, scores estimates of IRS spending based on a series of assumptions: about the nature of deterrence effects, about the nature of diminishing marginal returns with more audit investment, and about the relative return to focusing on higher-income individuals as compared to the population as a whole,” said Sprung-Keyser.

He hopes the paper, recently highlighted in a Washington Post opinion piece, will provide policymakers with useful data as they weigh funding for audits and the IRS as a whole.