Reinspired by true events

Tiya Miles’ research on Cherokee slaveholding sparked her first novel. A recent tribal reckoning led her to revisit it.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Tiya Miles — an expert on the intersections of Black, Native American, and women’s histories — would receive flashes of insight over the years while researching her subjects.

“However, these notions were speculative, personal, or emotional and had no place within an academic history,” said the Michael Garvey Professor of History and Radcliffe Alumnae Professor. “I think of these notions as the excess, or ephemera, collecting in my mind while I did the scholarly work.

“At some point, that spillover material became too compelling to push aside.”

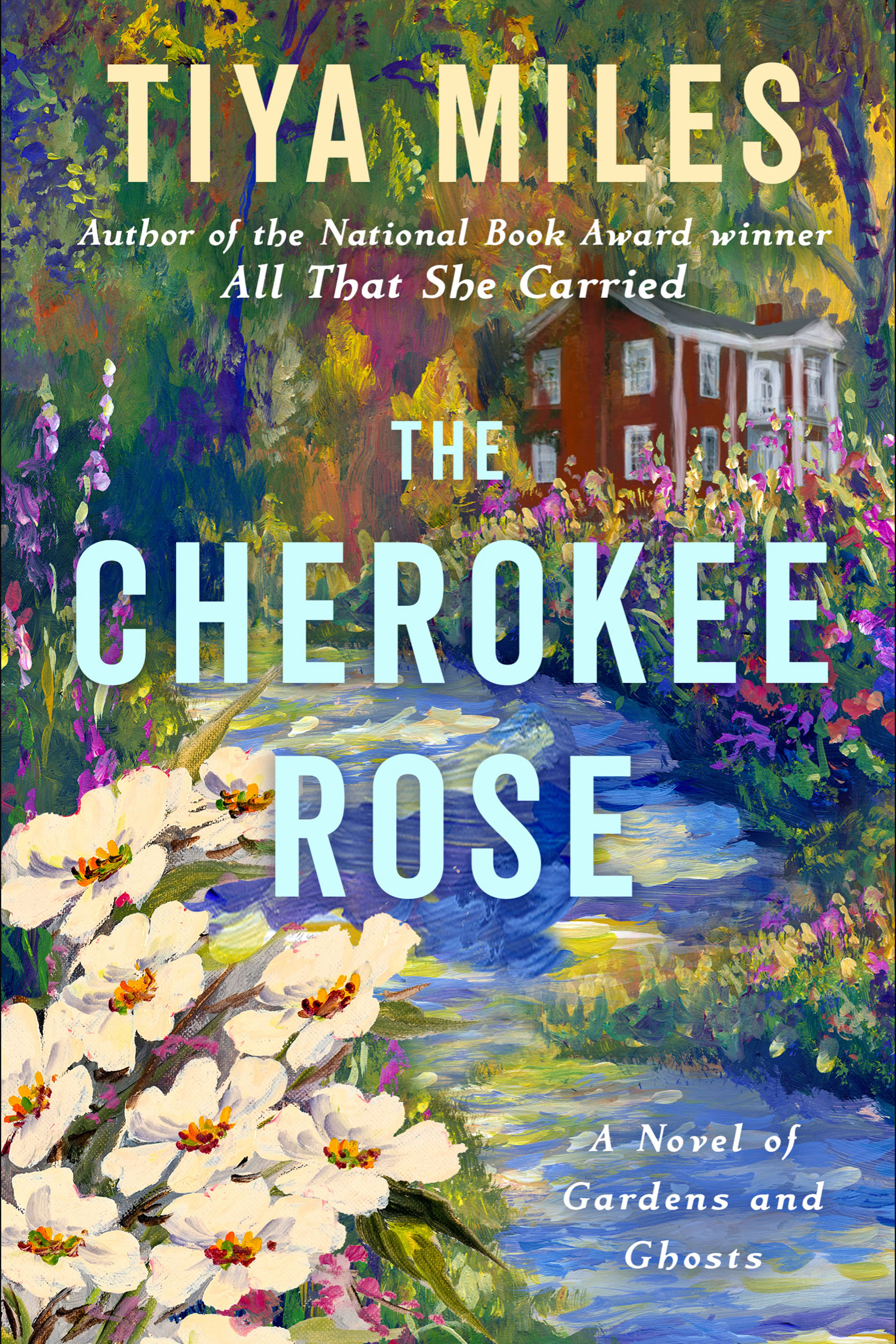

Miles gave these ideas a home in her debut work of fiction. First available in 2015 and rereleased last month with revisions and new scenes, “The Cherokee Rose” is populated by some of the real-life characters Miles discovered while researching a 1,000-acre plantation owned in the early 1800s by a Cherokee slaveholder named James Vann. The property, located in what today is Georgia, was the subject of Miles’ 2012 nonfiction book “The House on Diamond Hill.”

Set in 2008, “The Cherokee Rose” plants three young women of Black, Native, and mixed-race heritage on a fictionalized version of the Chief Vann estate. As the trio converges, their story becomes a fascinating study on 21st-century power and relationships. As they begin to uncover the property’s past, the book sees the lasting wounds of the racialized sexual violence widely practiced under slavery. And as the book’s many strands come together, the story hits upon that universal ache for belonging and a full accounting of our family histories.

We reached Miles via email to learn more about the re-release.

Q&A

Tiya Miles

GAZETTE: What initially moved you to revisit the Chief Vann House via fiction?

MILES: My historical research had revealed several key female figures from a range of backgrounds — Indigenous American, African, and European — who lived, worked, and formed families on the Vann plantation grounds. The enslaved Black women there were living in close proximity to the Native and white women who owned them or otherwise benefited from their knowledge and labor. Diary entries and letters written by a white missionary suggested complex relationships between and among these women but stopped short of describing how the women — even the missionary who held the pen — really saw and felt about one another across their various status differences.

For Black women, there was no equivalent written record. For Cherokee women, the written record was filtered through rare dictated or extrapolated missionary accounts. I wanted to view these individual women and their links to one another up close and from multiple perspectives, and I wanted to explore a counterfactual scenario in which they joined forces to challenge not only race-based oppression, but also patriarchal subjugation.

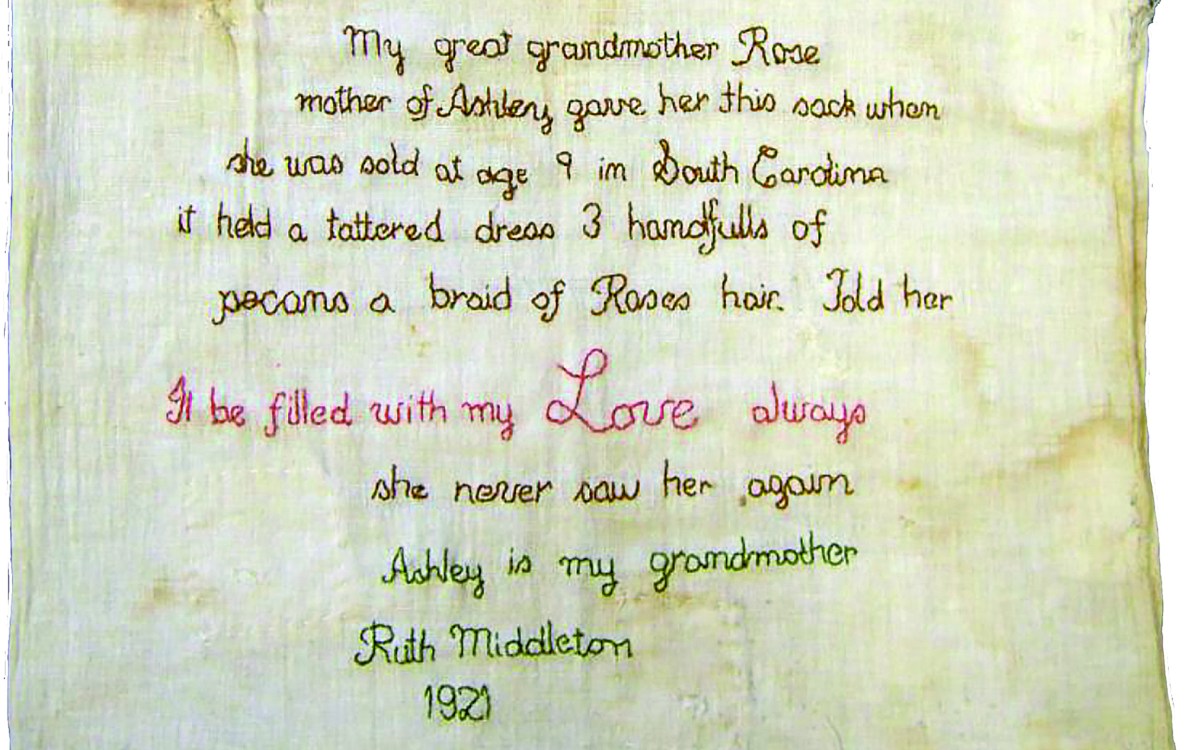

GAZETTE: You won the 2021 National Book Award in nonfiction for “All That She Carried,” a book that revives the stories of several Black women who nearly fell through the gaps of U.S. history. How did your work on “The Cherokee Rose” inspire your approach to the latter book?

MILES: I think of the terrain you’re pointing to here as a history-fiction border that is in fact a borderland with changing and sometimes ambiguous boundaries. For “The Cherokee Rose,” I started with a substantial foundation of historical documentation and moved into fiction writing based partly on that research and partly on my personal observations on the research trail.

With “All That She Carried,” I was endeavoring to reconstruct a past riddled with archival gaps. In the face of those gaps, I sometimes turned to classic works of fiction by Black women for inspiration and direction. Novels by Toni Morrison, Gayl Jones, Octavia E. Butler, and others helped me pose and begin to answer deeper questions about Black women’s experiences of enslavement and familial bonding. I drew on the imaginative work of others as a resource for my historical interpretations and arguments.

GAZETTE: Nonfiction books are often revised and rereleased to incorporate newly uncovered information. Did you apply the same thinking to “The Cherokee Rose”?

MILES: When I published the first version of the novel in 2015, the state of race relations in the Cherokee Nation was strained. There had been a long and painful battle over the place of descendants of enslaved people (“Freedmen”) in the contemporary nation. This Freedmen and -women population, which had gained citizenship rights in the Cherokee Nation following the U.S. Civil War, saw those rights stripped away in the late 20th century by Cherokee governmental actions. A string of court cases and a referendum ensued as descendants fought for inclusion (which would mean voting rights, healthcare coverage, educational access, etc.) and various arms of the Cherokee government fought to keep the descendants out.

This political history is too involved to be recounted in detail here. Readers might like to see an essay I wrote on the topic in the 2021 book “Time for Reparations: A Global Perspective,” co-edited by Harvard colleagues Jacqueline Bhabha, Margareta Matache, and Caroline Elkins.

By 2017, following a suit brought against the Cherokee Nation in a U.S. federal court, the Cherokee Nation, which had lost, did readmit Freedmen descendants to citizenship, but this action had resulted from pressure rather than moral conviction or remorse. Missing was a sense of generous welcome and an earnest desire for relational repair.

Fast-forward to the summer of 2020, following the death of George Floyd, when the entire U.S. nation and many of the Indigenous nations within its borders took a hard look at anti-Black racism. In 2021, the Cherokee American Studies scholar Adrienne Keene (at Brown University) asked if I was following the recent changes in the Cherokee Nation. Under new political leadership, the Nation had taken down a Confederate statue in the capital of Tahlequah, acknowledged a history of enslaving Blacks, admitted this had been wrong, and denounced racism. Tribal leaders launched initiatives in Freedmen/women history, culture, and the arts, even as Black and Afro-Cherokee descendants took on new civic and governmental roles. The Cherokee Nation was owning its history and transforming into a better version of itself. It was poised to become an exemplar of the bright possibilities for genuine repair (or reparations) that other formerly slaveholding tribal nations might follow.

A combined feeling of awe, relief, and gladness led me to revisit “The Cherokee Rose,” which had dealt centrally with the issue of Afro-Native identity, misunderstanding, and exclusion.