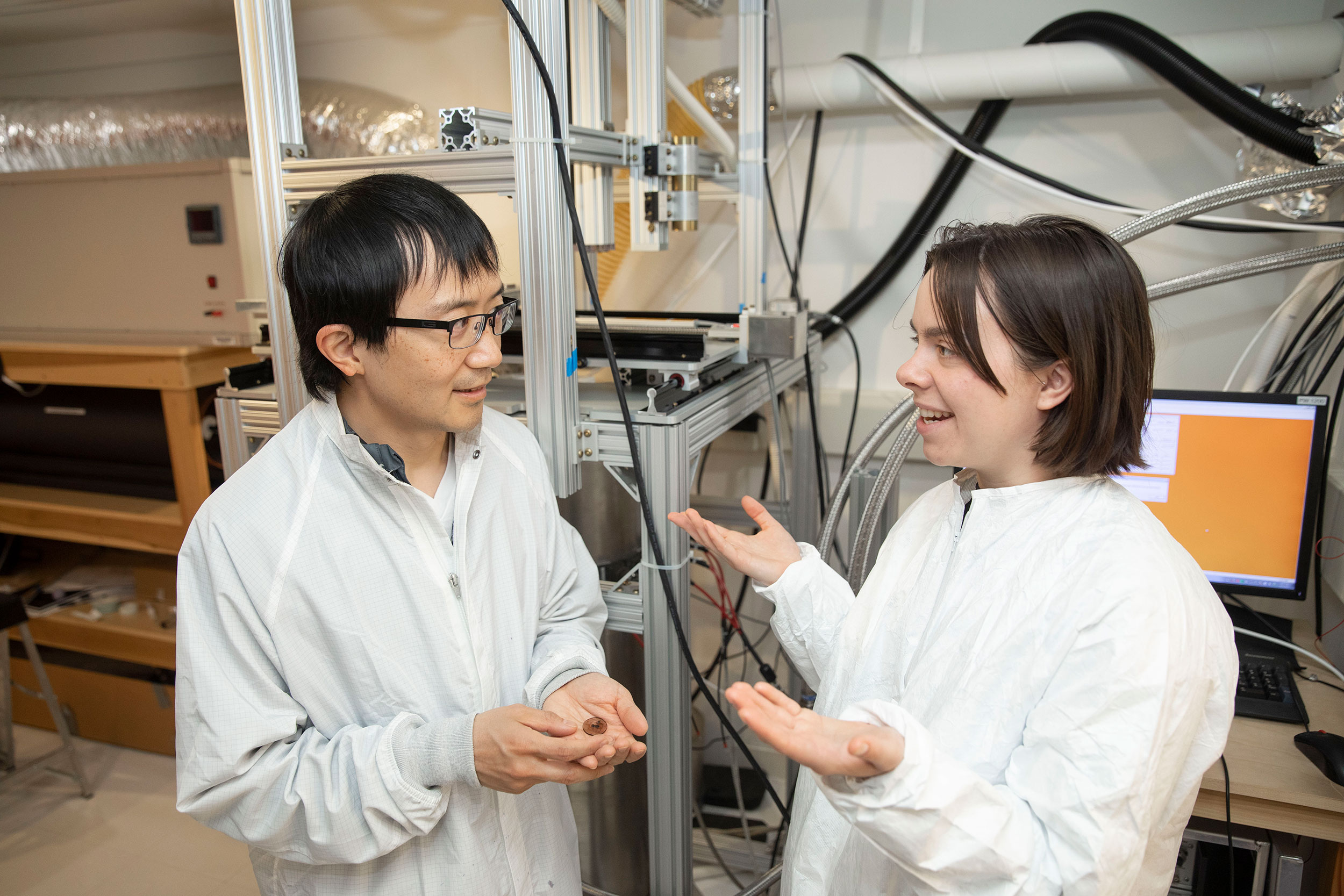

Associate Professor Roger Fu and graduate student Sarah Steele have uncovered evidence that Mars had a global magnetic field, much like Earth’s, for hundreds of millions of years longer than was once believed.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Life on Mars?

Study of magnetic fields suggests the Red Planet held water for longer than previously believed

Mars as we know it is a cold, dry planet, incapable of hosting life. But scientists believe this wasn’t always the case, and a recent study suggests that the period during which the Red Planet may have had liquid water on its surface — and the chance of life — was longer than previously believed.

A more detailed examination of a previously studied martian meteorite reveals the possible underpinnings of such a compelling prospect. Researchers in the paleomagnetics lab of Professor Roger Fu, John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Natural Sciences, have uncovered evidence that Mars had a global magnetic field, much like Earth’s, for hundreds of millions of years longer than was once believed. Such a field can deflect harmful cosmic rays, enabling the possibility of an atmosphere, with all that implies.

“On Earth, our magnetic field seems to do a good job of shielding our atmosphere from space radiation and solar wind,” said Sarah Steele, a third-year graduate student in Earth and planetary sciences and first author of “Paleomagnetic evidence for a long-lived, potentially reversing martian dynamo at ~3.9 Ga,” published in May in Science Advances. “We think that’s part of what keeps the Earth surface habitable.”

While it is still unknown if this happened on Mars, the new timeline increases the possibility. The research team looked for records of the planet’s magnetic field, which would represent evidence of an early martian dynamo. The dynamo, she explained, describes the way liquid in the planet’s core moves to make strong magnetic fields around the planet. “If the dynamo was longer-lived on Mars and if it played the same role, that may have helped keep the surface habitable longer. But on the other hand, the magnetic fields around Mars could have functioned really differently — maybe they even helped the atmosphere escape to space.”

Previous evidence had suggested that Mars had lost its dynamo — and its accompanying strong, planet-encompassing magnetic fields — 4.1 billion years ago, Steele said. However, with the use of an innovative new quantum magnetic field microscope, the researchers were able to place the loss at 3.9 billion years ago or later. “Those sound very close together,” she said, of the dates. “But a giant chunk of the stuff we are interested in, such as the questions about water, is in that window.”

“This showed that the commonly accepted timeline for the Mars magnetic field can’t be correct,” added Fu. “It’s likely it lasted at least 200 million years longer and probably even longer.”

The state-of-the-art quantum diamond microscope in Fu’s lab that supported the research examined samples from the Allan Hills 84001 meteorite, which had been retrieved from Antarctica in 1984. This super sensitive tool revealed that iron-sulfide minerals were strongly magnetized in different directions billions of years ago — back when the meteorite was still on Mars. Much like a compass is drawn to the magnetism of Earth’s North Pole, these minerals were reacting to Mars’ magnetic field.

These findings build on data gleaned by NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission, which orbited the planet beginning in 2014 and, among other research, worked to interpret remaining magnetic signals emanating from the crust, said Fu.

The data from Steele and Fu’s team also reveal that Mars’ magnetic field likely reversed at times, much as Earth’s does. While these reversals are currently not understood, ultimately they may offer some clues about Mars’ core, said Steele. “In the last few year we’ve gotten better estimates of how big the core is, and found out that it is mostly, or possibly entirely, liquid. Mars might have a solid inner core, but if it does, it’s very small.” By contrast, Earth has both a solid inner core and a liquid outer core. “That tells us that some of the chemistry in Mars’ deep interior is pretty different from what it is on Earth, which has some broader implications for how the planet was formed,” she said.

The researchers stress that much is still unknown about our planetary neighbor; however, the findings do allow some speculation.

“If the magnetic field on Mars was similar to Earth’s, then perhaps it also did a good job of shielding Mars from this energetic solar wind,” posited Steele. “Then, when the dynamo shut down, that could have been what actually caused Mars to lose its atmosphere. From that point, the atmosphere could have rapidly eroded away … And that then leads to the end of water — or liquid water — on Mars’ surface.”

There are counterarguments, including the suggestion that the magnetic field could have actually accelerated atmospheric escape, “so a longer-lived dynamo might have even helped Mars lose its water,” said Steele. “That would be really interesting since we’re still not sure how Mars lost so much of its water and atmosphere so quickly.”

At the very least, the finding “gives a better foothold for atmosphere evolution models to try to understand which processes were actually driving the climate change event that Mars went through.”

“It’s connected to understanding of atmospheric loss more generally,” said Fu. “This is part of a bigger-picture change in the field.”

This work was partially funded by the NASA Emerging Worlds program.