“We found that the increase in markups was mainly due to falling costs, and that falling costs were not being passed on to consumers in terms of lower prices. We had to dig in to find out why that might be the case,” says Alexander MacKay, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Retailers have been cutting costs, so why are prices still so high?

HBS research suggests firms have held off lowering them because it appears consumers got used to paying more

Early in the pandemic, airline tickets and hotel rooms could be had for a bargain because so few people were traveling. Used cars fetched prices way above book value due largely to supply chain disruptions, which added extra costs to all sorts of consumer goods, notably food.

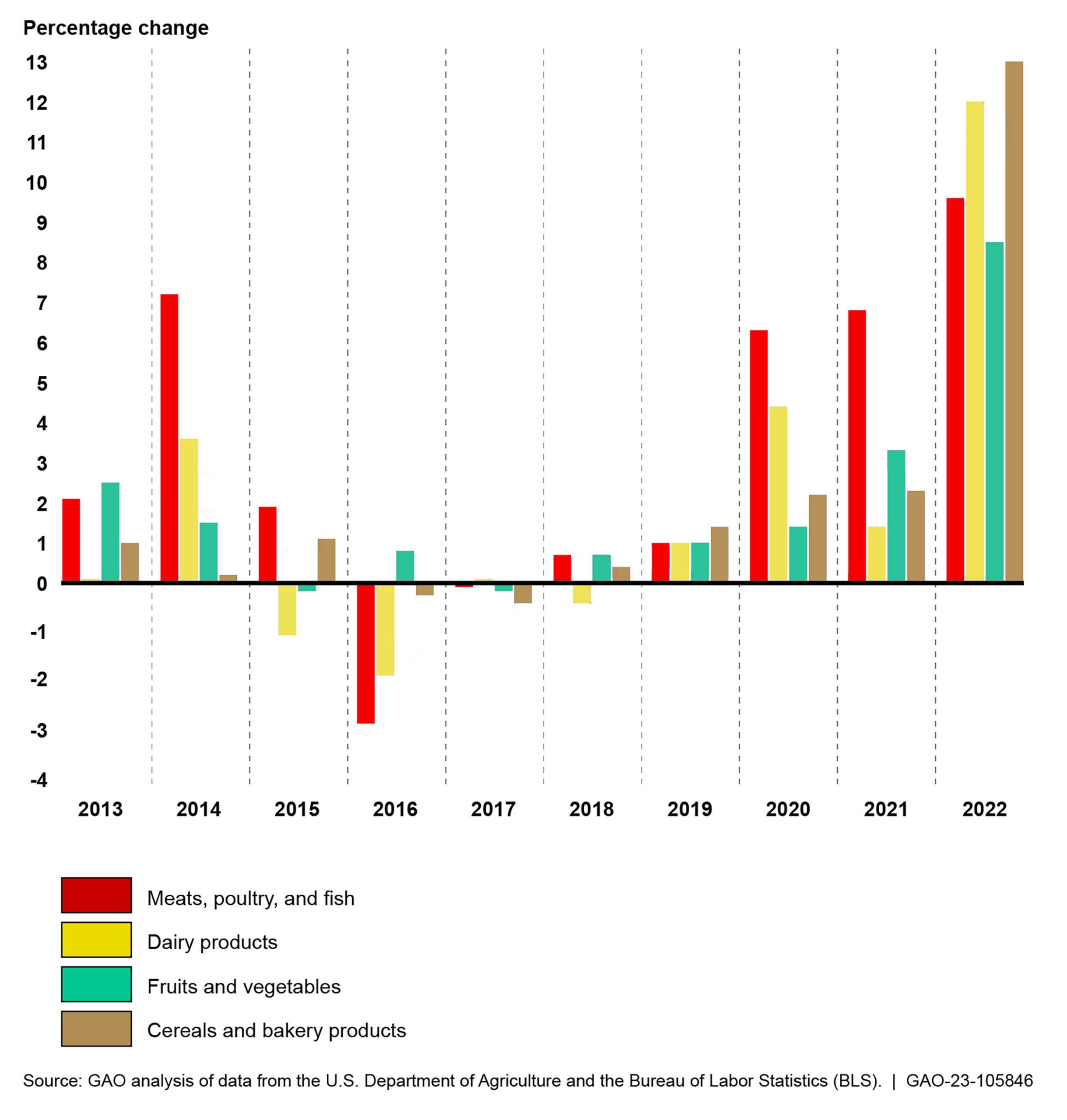

Most of those surges have largely eased, but grocery receipts remain stubbornly high. According to a recent congressional watchdog report, retail food prices rose 11 percent from 2021 to 2022, the highest annual increase in 40 years.

Even so, shoppers remain undaunted by higher prices, skipping money-saving practices like comparison shopping or clipping coupons. It appears to be part of growing shift in consumer behavior since 2006 that has allowed businesses that cut costs to pocket the savings rather than pass them along to consumers who seem to have grown accustomed to higher prices, according to a recent Harvard Business School working paper.

The Gazette spoke to one of authors, Alexander MacKay, an assistant professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, about this pricing dynamic. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Alexander MacKay

GAZETTE: You and your colleagues have been looking at the price increases of recent years to determine what’s driving it. What did you learn?

MacKAY: We examined markups for consumer products sold at grocery stores, drugstores, and mass merchandisers from 2006 to 2019. Our approach was to use econometric models to estimate the markups consumers faced on these products. Over this period, markups increased by approximately 30 percent.

At the same time, the prices on these products did not go up by all that much. They followed the rate of inflation pretty closely, increasing by about 2 percent per year. Instead, the main reason that markups increased was that the relative costs of these products, or the “real” costs once you adjust for inflation, had been falling. We were surprised that 1) markups had increased by as much as they had, and 2) this was mainly due to falling costs, not higher prices.

GAZETTE: A price increase is what consumers see at the checkout counter, but it’s not the same as a markup. Can you explain?

MacKAY: There are different ways you can define markup, but one common way is the price-cost margin — the variable profit to the firm from selling a product. This is the price net of the cost to them selling the good. Often, we take the dollar margin, the price minus the cost, and we divide this by the price to get a percent margin. You might see something like a 50 percent margin, meaning the price is twice the cost. If a product has a higher markup, but the same price, it means the company gets more profit for selling another unit of that product.

GAZETTE: Even before the pandemic, your research showed that markups on more than 100 everyday products like cereal, shampoo, and cold medication had climbed 30 percent. Why was that?

MacKAY: We found that the increase in markups was mainly due to falling costs, and that falling costs were not being passed on to consumers in terms of lower prices. We had to dig in to find out why that might be the case. Our econometric approach allowed us to look at several potential explanations, including changes in market concentration arising from mergers and acquisitions or changes in household demographics, such as in income or the presence of young children in the home. And we didn’t find that these elements explained much of what was going on.

Instead, we identified two key explanatory factors. The first is that, when markets are not perfectly competitive, companies typically don’t pass on costs one-for-one to consumers. The degree to which costs are passed on depends on demand conditions and the level of competition. If costs go up by $1, companies may raise their prices about 60 cents; if costs go down by $1, they may lower their prices by 60 cents. In the latter case, the margin goes up by 40 cents and the markup is bigger.

So, typically, when costs fall, markups go up because prices don’t fall as much as costs. We usually think this situation is a good thing — if firms are making things more efficiently, they can lower the cost of production. And our estimates imply that is happening in our sample: Costs are falling at a rate of about 2 percent per year.

If this was the entire story, then everyone would be better off because we’d have products that are produced at lower costs, and prices would be lower to consumers. Consumers would be happy, and companies would be making a little bit more profit, so they’d be happy as well.

But this wasn’t the entire story: Prices didn’t come down. They went up a little bit. The other part of the story, and the key second factor we identified, was that consumers were becoming less price sensitive over time.

GAZETTE: What is price sensitivity?

MacKAY: Price sensitivity can be captured by the following question: What discount would a consumer have to be offered in order to get them to switch from their most preferred product to a different product?

If I need a larger discount in order to switch, I’m less price sensitive. If I’m willing to switch between products for a 1 cent price difference, I’m very price sensitive. What we found was that consumers became 30 percent less price sensitive over our sample period.

In other words, bigger discounts would be needed to get consumers to switch products. A reduction in price sensitivity was not only happening for wealthier consumers. We found a fairly even decline for consumers across the income distribution.

GAZETTE: Consumers complain about paying more, but they are still buying, so is it fair to say they bear some of the blame for the persistence of high prices?

MacKAY: I wouldn’t say it quite like that. Companies set prices, and they do so in response to a number of factors. They account for the cost of producing the products. They account for competition, which will influence how much they can pass on cost changes to consumers.

They also account for consumer preferences. If consumer preferences change, then we should expect companies to respond. If consumers become less price sensitive, for example, we would expect companies to react by raising prices.

We found some evidence that our finding of lower price sensitivity might be indicative of a broader shift in consumer behavior. Over time, consumers have been using coupons less often. This is also consistent with a lower price sensitivity, as they might not be as willing to make an effort to save a few cents on the dollar. Relatedly, they may not be aware of how much they could save if they did shop around.

Consumers are also spending less time overall shopping. Now, there are two ways you can interpret this finding: One is that consumers care less about comparison shopping. Perhaps they are saving some time — “time is money” — and they might be better off.

On the other hand, consumers could be under greater pressure from other obligations, and they may just be putting up with higher prices due to time constraints. In that case, they might be worse off. We can’t really say which one of these is driving the changes in price sensitivity we observe, but it is an interesting subject for future research.

GAZETTE: Short of a radical overhaul of shopping behavior, can consumers do anything to prompt firms to pass along some of their cost savings?

MacKAY: Competitive pressures between firms do encourage companies to lower their prices. An individual consumer can make an effort to shop around, and there are consumers who do so. That consumer can benefit by finding lower prices. This can help others, too — even those who do not shop around — by making companies compete with lower prices to get you in their store.

It may be that there are fewer consumers out there who do comparison shopping. Anecdotally, it seems that more consumers are trying to get in and out of stores efficiently, and they have a good idea of what they are going to buy before they go in the store.

Some of this may be due to shopping habits. For the period of our study, prices did not go up by much. If prices were to continue to go up at a faster rate, we might see an increase in time spent shopping for lower prices. But it can take time for habits to change. And, ultimately, consumers would have to think that it is worthwhile for them.

Consider what happened with online retail. Originally, people thought that online shopping would make markets very competitive and lead to lower prices. Since it is just a few clicks to go from one online store to another, some expected that products would sell for essentially the same low price everywhere. Instead, the academic research, including some of my own, has shown that there is a lot of price dispersion for the same products across different online retailers. This means that consumers can shop around and get good deals, but not a lot of consumers do.

One reason for this is that consumers might have their preferred online storefront just like they have their preferred brick-and-mortar retailer. So, to the extent that consumers are tied to a particular store or have a particular routine, this would reduce the competitive pressure among retailers to lower their prices.